Pablo Weisz, son of the renowned surrealist painter and writer Leonora Carrington, asked his mother to leave him the house in Mexico City where the artist worked, raised her children and lived for 60 years. “I want to make a museum of yours, of your work,” Weisz promised. The project began to take shape in 2017, when the authorities of the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM) acquired the property on Chihuahua Street, in the Roma neighborhood. The university invested 12 million pesos (about $600,000) between the purchase and remodeling of the residence and in 2021 the place was ready and those in charge of the project were only waiting for the approval of the university to be able to open the museum to the public. . Then plans changed. Sources close to the project affirm that it has been stopped due to a dispute between the university union and the UAM, from where they now report that it will remain closed and will only be a research center.

Weisz not only sold the house, but also gave more than 8,000 of the artist’s objects on loan. Those close to the project consulted by this newspaper point out that the main obstacle is a disagreement between the union and the UAM, although they also accuse the university authorities of “lack of political will.” “Any space in the university has places controlled by the union and each rector has to develop a model of relationship and negotiation with them,” they say. “If an agreement is not reached in the negotiations at the end of the year, every February the workers go on strike. In this case, due to the characteristics of the project, administrative and work profiles must be established that are difficult for the university, because it is a museum project and I believe that the management of the current rector does not have a specific commitment; managing it has not been in their political interest,” say these sources, who have asked to talk in exchange for anonymity. The rectorship of the university is headed by José Antonio De los Reyes Heredia, who concludes his term next year.

The surrealist painter Leonora Carrington died in Mexico at the age of 94 in May 2011. Her friend, the writer Elena Poniatowska, had won the Biblioteca Breve Prize a few months ago for a book about the exciting life of the artist, whose work has sparked interest from specialists and the public, who waited with great expectation for the opening of his house converted into a museum to be able to tour room by room the place where Carrington was inspired and created much of his work, see its intimate spaces, the family kitchen, the living room , the creator’s studio and the internal gardens, where she planted a jacaranda that has grown so much that it is now taller than the house. A place similar to Frida Kahlo’s famous Blue House, in Coyoacán, south of Mexico City. Pablo Weisz donated 45 sculptures to the museum, mythical anthropomorphic figures that are distributed in each of the rooms.

“The university was never on the verge of opening the house, that battle would have to be fought,” say the people consulted. “The house was remodeled, the university made the investment, everything formal was done, but negotiations had to be done with the union about the positions, profiles, people who have to occupy positions such as the ticket taker, or those who guard the rooms. These profiles are not determined within the UAM and had to be negotiated. We looked very bad to the public, because the house was left up, but there was no opening,” the sources claim.

Yissel Arce Padrón is the general coordinator of UAM Culture Diffusion, the area in charge of managing all artistic projects. Arce Padrón explained to EL PAÍS during an interview at the rectory headquarters located in Tlalpan, south of Mexico City, that they have decided that the Carrington house will remain as a “documentation center” and not as a museum open to the public. public. “The UAM is interested in acquiring Leonora Carrington’s house with two perspectives: an idea of a studio house and a documentation center, because basically the university’s interest is investigative. We are an extension, through these cultural programs, of what happens in teaching and research,” explains Arce Padrón. “There is no fixed museum model beyond this articulation with research as part of artistic and cultural practices,” he justifies.

Her colleague, David Sánchez, director of academic and cultural links, reinforces her argument and states that the project “is more about documentation than about openness to the public, to recover the themes that were important to Leonora Carrington in her work in Mexico. such as surrealism, feminisms, exile, which goes through her entire family, including her husband Emerico Chiki Weisz, who was a very important photographer and who recovered Robert Capa’s negatives during the Spanish Civil War so that this material could be exhibited to the public.” Sánchez explains: “Those are the lines that we are interested in exploring, leaving space for new researchers who propose creative projects. It is not about doing another thorough review of her biography, or her work, but rather we wanted to work on this shift to distance herself from museums like Frida Kahlo’s, which is a more traditional museum, open to the public, where lines form. and many people attend to learn about everyday objects,” he adds.

Aggi Garduño

The UAM announced the inauguration of the project on April 7, 2021. In a statement issued then by the university, Francisco Mata Rosas, general coordinator of Diffusion, assured that the Leonora Carrington Study House is part of a program that links the offer cultural with the academic objectives of the UAM. “We have established alliances, agreements and working links with both the federal and local sectors, as well as with independent groups; The great artistic and documentary value that this place contains allows us to continue consolidating the offer for our research groups, teachers and students, but it will also of course be a great tourist and cultural attraction site,” he said.

“These are empty words, because they have not finalized the project, which is important for the cultural world of the city,” says Rodolfo Pérez, who was general secretary of the UAM workers’ union. Although Pérez retired in April, he was in the negotiations for years. He assures that the opening of the house has not occurred due to the will of the authorities and not because of the workers’ closure. “We have been discussing this issue with the university for several years,” he says by phone. “The university has responded to the union’s requests by saying that the house is an academic project, they always disguise it like that, when in reality it is a study house where there will be various cultural activities. What they have told us is that it is in the process of construction and conditioning,” says Pérez.

The union, he says, asked the authorities to open 17 jobs in 2021, as established by the collective contract agreed with the institution. “Clearly, it is established there that this contract will govern all university locations, which regulates the labor relations of both academics and administrative workers,” he explains. Among the positions requested were cleaning workers, security guards, secretaries, cultural promoters, and sound and lighting technicians to guarantee the quality of the exhibitions or cultural activities held at the site. “The university has already started this project and has been violating the collective bargaining agreement, because it has not hired basic personnel, but it has hired trusted personnel and for the cataloging of the collection that Leonora left in that house,” says Pérez.

“What the university has done is use the union as a pretext to not carry out a project that they have an obligation to carry out. If they made a commitment, and have already allocated funds, it is regrettable that at this time they have not finalized it. What there is at bottom is a lack of strategic planning and above all of discretionary management of the budget, because if they had a rational administration of the budget, it would be enough to open that house,” he concludes.

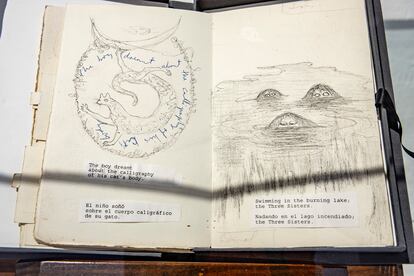

Yissel Arce Padrón denies that there is any dispute with the union and that this is the reason why the house is closed to the public. “The issue of places, not only for cultural spaces, but for the entire university, is always very controversial and has to do with other economic implications, with how the public university receives financing from the Government; What can’t be done and what can be done. In this specific case, since it is a university space, it would imply a negotiation that has not occurred with the union. Actually, there is no dispute. The study will remain as a research center,” he reaffirms. Arce Padrón says that those who are interested in learning about Carrington’s work can see the exhibition that the university has mounted at the Metropolitan Gallery, in the Condesa neighborhood of the capital, entitled The acoustics of Leonora Carrington. Art, writing and feminism, inaugurated on July 25 and which brings together sculptures, engravings, sketches, drawings and unpublished works in embroidery and papel picado by the artist, as well as some pieces from her house on Chihuahua Street.