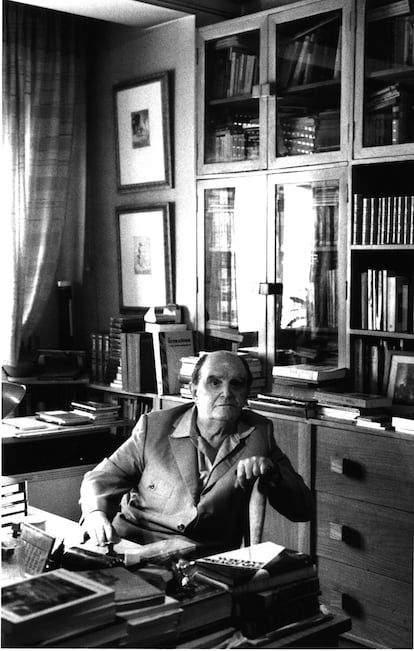

The mythical stage of Tangier International had its best chronicler in Emilio Sanz de Soto Lyons (1924-2007). He gave voice to his memory, projecting onto that mythical setting the halo of a fascinating and unrepeatable world. There he met everyone there was to know, shared his stories and secrets, and told the world like no one else the mysteries of that enchanted city that lived ahead of the forbidden modernity on the other side of the Strait. Confidant of Jane Bowles, Carmen Laforet and Geraldine Chaplin. A student of exile cinema and the Spanish footprint in Hollywood, he collaborated with Saura and other filmmakers, such as Buñuel and Borau, contributing from his tangerine vantage point sense and sensitivity to the weak Spanish culture of Francoism. It was the beacon of modernity anchored in the most international Tangier. At the time of his centenary, it is necessary to highlight the importance of his work and his teaching.

Captivating, talkative, giving. Perhaps better than any other, this last word suited him, which according to the RAE includes being “generous, selfless, splendid, liberal, determined, folksy, maniacal and sensible.” Emilio was all that and at the same time the best guide to decipher the human map of Tangier. When I interviewed him to share his memories of that period, he enthusiastically described the Tangier-based American writer Jane Auer Bowles, stating that “Jenny was a kind of continuous fireworks, which in a certain way wasted part of her genius. Well, he wasted it, but those of us who were his friends received it.”

This description should be applied to Emilio himself, who spread his knowledge, brilliance and evocative capacity in so many conversations, talks and classes taught, but without leaving a written work at the level of his wisdom. Emilio’s spoken teaching was of such magnitude that, paraphrasing, those who were his friends recognized his genius, his fireworks, his brilliance and his contribution to the opening and modernization of the Spanish cultural narrowness of the 1950s and 1960s. His sister Lydia smiles tenderly as she comments that “anything you asked him, he would give you a four-hour talk. You didn’t dare ask because it went on so long that it never ended. “He would have been a good professor.” It really was. His teaching on the history of cinema was especially received by American students who attended his classes at the International Institute on Miguel Ángel Street in Madrid. The patina of international Tangier never left Emilio. Son of an English woman from Tangier and a man from Malaga sent to run the Bank of Spain in Tangier, Emilio embraced cosmopolitanism and culture in freedom.

He also left a series of works on film history that are preserved in two volumes under the generic title You come from an old memory, divided into a chapter “on letters and art” and another “on cinema”, included within the legacy that today is guarded by the Student Residence in Madrid, which has 4,000 records including books, magazines, letters and photographs.

He corresponded with Buñuel and the greats of Spanish cinema of the time. There is an important correspondence with Bardem, Patino, Berlanga, Muñoz Suay, Marsillach, Paco Rabal and Borau. But the most abundant correspondence was with Carlos Saura and Geraldine Chaplin. He was a film scholar who fascinated the youngest Spanish filmmakers of the sixties and seventies with his knowledge, who turned to him as a living encyclopedia.

His great passion was discovering and recounting the adventures of the Spanish in the mecca of American cinema. Exile cinema was his forte. Angelina and the honor of a brigadier (1935), directed by Louis King, alone justifies Spanish cinema made in Hollywood, with the contributions of Jardiel Poncela’s script and the performance of Rosita Díaz Gimeno, who would marry Negrín’s son in exile. Sanz de Soto firmly believed that “Spanish cinema cannot be separated from our Silver Age. Although their contribution was minimal, some names that made this cultural resurgence possible approached cinema with greater or lesser fortune,” he said: “I think of Buñuel, Neville, Jardiel, Eduardo de Ugarte and even two exiled actresses, Catalina Bárcena and Rosita Díaz Gimeno.” Sanz de Soto must be recognized as an authority on the subject, who studied its internal and international aspects like no one else. Some of these matters were the subject of his correspondence with Buñuel (“your letter is the most interesting I have received in my life”) or Borau.

To date, his back-and-forth correspondence with Carmen Laforet is the only one explored and published in full, in a detailed edition by José Teruel, with whom he coincided as a professor at the International Institute. Teruel describes him as “a man of great intellectual curiosity, enormously cultured and with great artistic intuition, also endowed with grace, kindness and immense generosity.” He concludes by pointing out that he was “a defender of the third Spain or a possible Spain.”

The Tangier atmosphere gave Emilio a long and clean look, without fears or restrictions, although he already had to suffer criticism and reprisals from the Francoist authorities in the protectorate city. “You look like the lady from Elche, the eternal stranger,” Saura tells him in one of her very long and frequent letters to Emilio. It would be very important to rescue them for a complete portrait of the Aragonese director who talks about impossible projects such as carrying The Jarama From Ferlosio to cinema, he refers to issues such as “the problem of how to insert documentary with fiction”, but above all he confesses his doubts when facing some projects and even secrets about his relationships. A naked sentimental Saura. “I really like Geraldine, but let it stay between us.” Sixty-six letters sent by Saura are included in the legacy, covering the years 1960 to 1994. Without a doubt the most special and fun letters are those written by Geraldine, who developed a complicity with Emilio like that of Laforet. “Emilio knew more about her father (Charles Chaplin) than she herself,” says his sister Lydia.

Emilio was art director on Saura films (Peppermint Frappé, Stress-It’s Three Three), and finally left a withering Tangier to settle in Madrid. The interest of the filmmakers would also be followed by that of other Spanish artists who sought in Emilio the remnants of that mythical and mythologized Tangier.

Sanz de Soto remembered that the summer of ’49 was the most explosive in the history of international Tangier. The foreign residents’ capacity for waste and enjoyment was unlimited. Paul Bowles portrayed her in his novel Let it come down (Let it fall). Money was flowing and there was great permissiveness. The artists found there a glorious refuge touched by the sand and water of North Africa. Emilio Sanz de Soto kept a vivid memory. This is what he told us in the documentary Water and sand maps: “The truth is that this North American group, which has mythologized Tangier, especially within the Anglo-Saxon world and now within the world in general, lived totally outside the life of Tangier. They lived in El Farhar, which was a truly heavenly place, where there were some small bungalows, and they had that wonderful American thing that, even if they had gone to bed at five or six in the morning, with plenty of whiskey in their bodies, they all worked in the morning. It’s something that always amazed me with horror. You would arrive in El Farhar in the morning, and hear all the typewriters working and hear Paul composing at the piano, this was something that fascinated me, because at a certain time everything stopped and they used to go down to the beach.”

In his own enthusiastic and particular way, Emilio has been a beacon for all lovers of the Tangier dream. Our favorite tangerine. Living and walking history of a golden age, which he was forced to remember and tell gladly and repeatedly at the whim of new generations fascinated by the mythical city of Bowles and Capote, Barbara Hutton and Jane Auer. He was the son of the director of the Bank of Spain and the stock market of the North African city, whose reality, entangled in stories of espionage and border businesses, surpassed the scripts of Casablanca or novels let it fall. Emilio lived it like no one else of his time. He flitted among the Christian families of that multicolored Tangier, between the Jewish celebrations and the splendor of the Kasbah mortuary. He saw everything and removed it. He cheered painters, like Runyan and Pepe Hernández. He moved the cinema club with Pepe Carleton. He was enthusiastic about literature and praised his close friend Ángel Vázquez, author of The bitchy life of Juanita Narboni.

He went out for the last time in public, now in a wheelchair, to pay tribute to his dearest Geraldine Chaplin, at the Film Academy’s gold medal dinner. Geraldine was his favorite woman, as were Carmen Laforet and Jane Bowles before her. Like them, he experienced his own doubts and anguish. We all encouraged him to write more, to complete one of those memoirs full of wisdom and characters, but he preferred to recite them in his classes for North American students and in gatherings for friends, showing himself as a living monument of the memory of an unrepeatable city. . The soul of Tangier had inhabited Emilio forever, and he made us dream and feel it forever.