For for British writers, membership of the Royal Society of Literature (RSL) has long meant that your most illustrious peers have agreed that you have written at least two works of literary excellence. Wordsmiths such as Nick Cave, JK Rowling and former Archbishop Rowan Williams are recent. Once a writer has been formally invited, they attend a ceremony where they choose a dead light pen (a quill of Lord Byron, George Eliot or even Charles Dickens) to write their name in the Roll Book of Fellows. Then they can mingle at the RSL’s annual summer party with the likes of Monica Ali, Zadie Smith, Ian McEwan and Kazuo Ishiguro.

For over 200 years, the RSL, founded in 1820, has glided along like Jane Austen’s tea party. Established under George IV, early presidents included bishops, princes, barons and earls. Tory bigwig Rab Butler was one long-serving president, as was Roy Jenkins. But while the society’s early history looks like a well-established old boys’ club, things gradually evolved.

In 1908, the first female members were elected, Alice Meynell and Margaret Woods. The RSL officially became a charity in the 1960s and finally in 2017 had its first female president, Marina Warner. For years the society was housed in an elegant building off Hyde Park Gate – “like walking into a Turgenev novel”, one insider told me. However, failing to secure a lease, it has since moved to more modest premises at Somerset House, while its archive was sold to Cambridge University Library.

All of these changes, however, seem minor compared to the seismic shifts and controversies of recent years, setting the stage for a tumultuous AGM today. There has been outrage, backbiting, plenty of leaks and claims that the organization was on the brink of collapse.

There was fury among fellow members at the RSL’s decision not to issue a statement of support for Salman Rushdie following his stabbing – felt particularly keenly by older members who had risked their safety to support Rushdie when the original fatwa was issued.

Initiatives aimed at making the community more inclusive and representative have also experienced a backlash. 2018 saw the launch of the ’40 Under 40′ drive, which aims to ‘welcome a new generation of British writers to the RSL’, with the panel chaired by author Kamila Shamsie.

Several fellows complained about the dilution of the criterion of excellence and were upset when the reading public was asked to nominate writers they felt were overlooked. An exasperated colleague told me, “You open it wider and wider until you’re in all the must-reward situations and there’s no credit left.” Author and critic Philip Hensher declared: “It is truly appalling to watch this little clique transform one of the most inclusive and generous organizations in the country into a bitter and exclusive little club.”

Another controversy involved an issue of the RSL magazine that was pulled for censorship, which insiders claimed was the censorship of an article about a Palestinian literary festival that had been critical of Israel. The paper was eventually published, but its longtime editor Maggie Fergusson was released.

Many also deplored society’s failure to stand up for their colleague Kate Clanchy, who was subjected to a barrage of online abuse after she was accused of using racial stereotypes in her award-winning book. Some of the kids I taught and what they taught me. Although he was defended by the pupils he wrote about, Clanchy resigned from the RSL after one of his harshest critics was made a Fellow.

Private investigator described these events as an “ideological purity spiral” disguised as a drive for diversity. However, modernizers of the RSL claim that the summer party now looks a lot less like the farewell party of an elderly Oxbridge academic than it used to. I know because I participated in the first post-lockout fight in 2022 with my newly elected colleague, Monique Roffey. He won the 2021 Costa Award for the best complete book with his novel. Black Conch Mermaid.

Roffey told me how thrilled he had been to be invited “as an outsider in UK literary circles”, but how it was now “very painful to hear the opposition to a whole bunch of new writers being invited”. He said: “Today I go to RSL meetings and parties and I see my generation of writers represented. I don’t feel so much of an outsider. Surely more diversity must be celebrated and embraced as a very positive thing?”

After a busy year, it was revealed last week that director Molly Rosenberg is leaving to “pursue new career opportunities” and chairman Daljit Nagra will step down after four years at the AGM today.

That might satisfy the over-65 group, which makes up more than half of the current membership, but behind the scenes, many of the younger guys believe Rosenberg was being unfair. During his tenure, six new RSL awards and prizes were established (including the Sky Arts RSL Writers Award and the Jerwood Poetry Award), women’s pens were used for the first time at the signing ceremony, and the number of vice-presidents doubled, including writers such as Jackie Kay, Mary Beard and Simon Armitage. Rosenberg also launched the RSL 200, a bicentennial celebration that spanned five years and included many high-profile events.

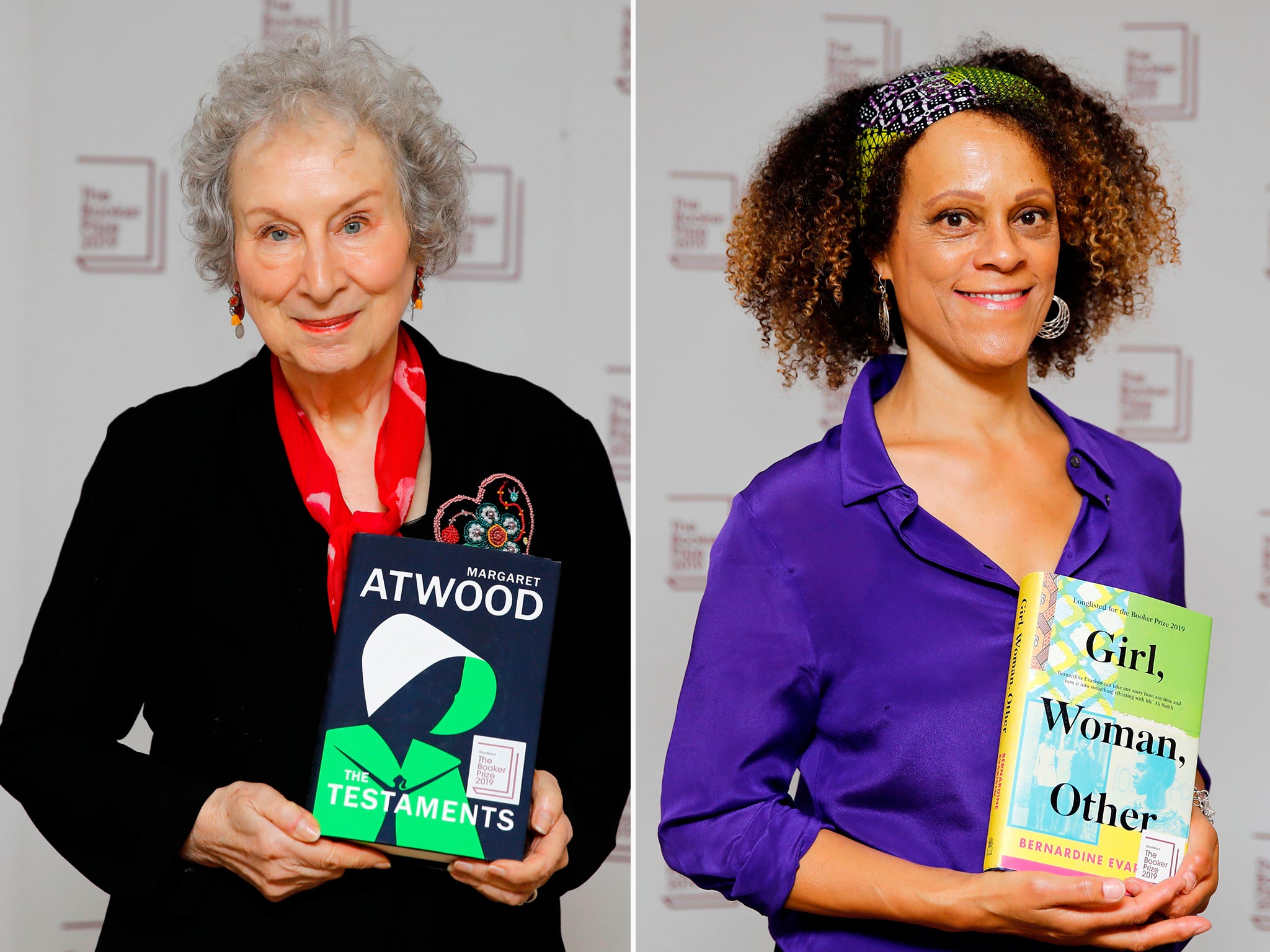

Bernardine Evaristo, the current president of the RSL, defended the society and Rosenberg over the Clanchy and Rushdie cases, stating: “The role of the society is to be the voice of literature, not to present itself as the ‘voice’ of its 700 fellows”. (It is noteworthy that Evaristo sent a personal message in support of Rushdie.)

But therein lies the problem: the guys can’t seem to agree on what the RSL’s “mission” should be. Is it a place to meet and celebrate the crème de la crème of British literature? Or is it a campaign group defending writers and contemporary literature? Is it a refuge for those who immerse themselves imaginatively in other people’s experiences? Or should it have an explicit duty to reflect societal changes and represent diversity?

One thing became clear to those closely involved: The RSL is a Georgian society grappling with a 21st century culture for which it was not built or equipped. At the expected general meeting, the findings of the society’s first governance review will be presented and discussed, and minds may boil over.

For gossipy, book-loving outsiders like me, the internal struggles have opened up fascinating lines of inquiry. Anyone can visit the RSL website to see who is – and isn’t – a mate. Multi-million selling Ken Follett is; multi-million seller Matt Haig is not. Neither is Christie Watson, despite winning the Costa for her debut novel, a heart-piercing memoir of frontline nursing and a professorship at UEA. Where is comic writer Craig Brown after winning the Baillie Gifford? Or are Old Etonians banned now?

No selection panel can please everyone. Literary controversies are notorious (I’m still pondering Tibor Fischer’s declaration in 2003 that Martin Amis’s novel Yellow Dog was so “terrible” that it was “like your favorite uncle getting caught masturbating in the school playground” and often outlived novels or authors. I was a Booker Prize judge in 2004, and a few writers gave me the cold shoulder for years afterwards, believing it was my stupid fault they didn’t win.

The RSL storm shines a stark light on the broader struggles of the publishing world. Many older, established authors don’t get the advances or sales they once took for granted. This inhospitable landscape coincides with publishers launching initiatives to find young, diverse writers from ethnic minority or socially disadvantaged backgrounds.

Those who once dominated literature feel pushed off their perch, just as the middle-aged and middle-class complain about the same thing happening in business. Culture wars are raging from gender-critical views to “trapped” investments in everything from Israel to oil. Ethical purity has resulted in literary festivals losing funding and many writers losing friends and influence.

This collision has affected all the antiquated British institutions. The Garrick Club retreated into the 21st century when its governing body realized that barring women from membership was leading to a mass exodus. Oxford and Cambridge are under constant scrutiny because of their overrepresentation of elite school students. Pidi’s screams can be heard everywhere, as if a sadistic dentist has been let loose in the castles of privilege.

My prediction is that whatever happens at today’s AGM, the most painful part of RSL’s transformation will have faded. No one on either side wants society to collapse. If there’s anything worse for a writer than being a guy, it’s the prospect of never having a signature flourish with Byron’s pen.