If the faithful of photography had to choose a god, it would most likely be Henri Cartier-Bresson, due to the quality and variety of his work and his long career. The Frenchman Cartier-Bresson (Chanteloup-en-Brie, 1908-Montjustin, 2004) was, as he has been called, “the eye of the 20th century.” Through the lens of his 35 millimeter Leica camera he passed from Spain in the 1930s to May 1968 in Paris, and along the way, wars, revolutions, falls of tyrants, rises of others, artists, intellectuals and people. on the street When 20 years have passed since his death, on August 3, the KBr photography center in Barcelona remembers him with an exhibition that orbits his career. There are 240 images, original copies, because Cartier-Bresson stipulated that no new ones be made after his death.

The exhibition, titled Henri Cartier-Bresson Watch! watch! watch!, by one of his phrases (“I am a visual man. I observe, I observe and I observe”), can be enjoyed until January 26, 2025. It is organized by the Mapfre Foundation and the Bucerius Kunst Forum, an art museum in Hamburg, where it has come, in collaboration with the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation of Paris.

Once the presentations have been made, it is time to explain why the work of someone who defined himself as a craftsman, not as an artist, is inseparable from his great eye for capturing “the decisive moment”, of which the well-known image from 1932 called is its paradigm. Behind the Saint-Lazare station. In it, A man, actually a shadow, jumps over a flooded area where he is reflected in the water. The expression originated when he published his first book, in 1952, Images at La Sauvette (Sneaky Images), with a beautiful cover designed by Matisse, which in the US was titled The Decisive Moment. It is the publication that launched him to fame, although he had already been working for two decades. Here is his definition of what he did: “A photograph is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the meaning of a fact and a rigorous organization of the visually perceived forms that express that fact.”

The copy that opens the exhibition is a sui generis self-portrait, from 1933, in which an extended sleeping bag is seen from which his right foot appears. He did not like being photographed, as he showed years later at a press conference in New York, in which, as the photographer and theorist Manuel Falces recalled, he turned around so that they would not photograph him. In the exhibition there are some more images of him with his camera hanging from his neck, with which he moved, as Truman Capote would say, “like an excited dragonfly.”

His beginnings in the image were through surrealism, an avant-garde that he came into contact with in the cafes of Paris, where he met André Breton, Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí. They are photos of everyday motifs that he converted into geometric compositions. After a trip to Africa, he decides to dedicate himself to photography. His friend Robert Capa encouraged him to try photojournalism, which he would turn into a humanist work.

His first assignment came to cover the 1933 general elections in Spain. Sympathetic to the Republic, there are his classic photos, those of prostitutes and children in Alicante, for example. In November of that year, his first exhibition on Spanish soil was held at the Madrid Ateneo (sixty years later, when he came for an exhibition at the Reina Sofía Museum, a camera and his wallet were stolen at the Retiro). He also spent almost a year in Mexico, where he learned to speak broken Spanish.

Henri was from a wealthy family of textile businessmen, but since in his youth he aligned himself with the French Communist Party, he felt class modesty and began signing his photos hiding his compound surname, like Henri Cartier or H. Cartier. He would eventually be the first photographer to be known by his initials, HCB. His economic position had made it possible for him to try what he liked, painting, with classes in artists’ studios, to be able to detach himself from the future that awaited him, taking care of the family businesses.

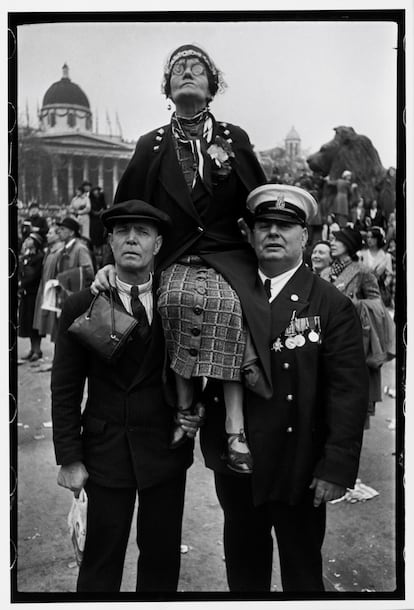

In May 1937, he made a report for the communist newspaper This evening about the coronation of the English king George VI in London. Cartier-Bresson avoided the images that could be foreseen, those of royalty, and preferred an original and fun vision, focused on the public, on their gestures and on the optical devices with which they tried to see the ceremony.

Called up during World War II, he was taken prisoner by the Germans at the end of June 1940 and sent to a prison camp, a three-year ordeal until the third attempt he managed to escape in July 1943 to join the Resistance. . When asked, after having been all over the world, about his favorite trip, he answered: “My three escapes from the prisoner of war camp.”

From those years is one of his best-known series, the one he took in a displaced persons camp in Dessau (Germany) of a woman discovered as a whistleblower by a woman she had denounced. He also portrayed the liberation of Paris, images of which he did not recover the negatives until 25 years later, in a cookie box in his mother’s house after her death.

HENRI CARTIER-BRESSON FOUNDATION / MAGNUM PHOTOS

It was after the war when, convinced by Robert Capa, he joined the founding of the Magnum agency in 1947, a cooperative so that photographers could produce their own work and defend their rights as authors. They would make it a world reference in photographic reporting. Both, along with George Rodger, David Chim Seymour and William Vandivert put up $400 each and shared the world. Cartier-Bresson decided that he wanted to photograph Asia, which enabled him to photograph Mahatma Gandhi in January 1948 hours before his assassination, as well as the cremation ceremony. Also from that year is his report on the civil war in China, from which the People’s Republic would emerge, with its snapshots of the chaos of the disintegration of the previous regime.

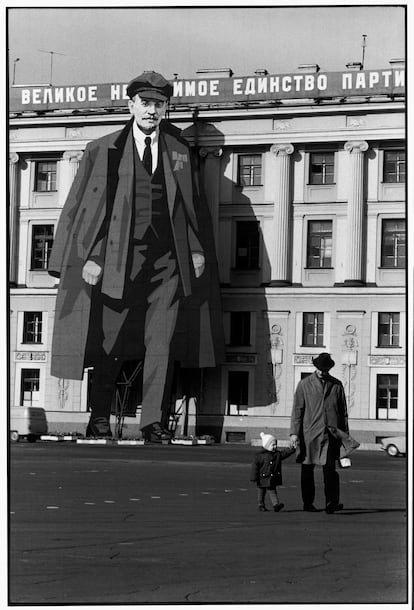

Then came his reports on the Soviet Union, criticized for showing a complacent view of the monster of communism; East Berlin a year after the construction of the Wall, or Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Cartier-Bresson often displayed his sense of photographic humor, such as in the image of a young Cuban woman sitting on the street with a rifle in her lap in front of a window advertising Valentine’s Day. Over the years he adopted a healthy skepticism about his mission: “I don’t have a message, nor a mission, (…) I have a point of view.” However, the human being was always the center of his photography.

A contributor to the most important magazines, he traveled from one end of the world to the other in a professional frenzy: racial segregation in the United States, with portraits of the leaders of the black community, such as Malcolm X in a Harlem restaurant in 1961, or Martin Luther King; neorealist Italy and the barricades of May ’68. This trip through the 20th century closes with photos of the first feminist demonstration in New York, in 1971. Once again she looked away to portray three guys with horn-rimmed glasses, ties and looking like they didn’t understand anything they saw.

Shortly afterward he distanced himself from Magnum, among other reasons, because the magazines had imposed the use of color, which he did out of pure obligation. So he retired to return to his beginnings, those of drawing and painting.

The end of this magnificent exhibition is a gallery of his portraits of intellectuals: like the famous one he made of Sartre, who smokes a pipe on the Pont des Arts in Paris; that of Giacometti protecting himself from the rain with a raincoat, as if he were one of his figures; Coco Chanel smoking defiantly, Arthur Miller… It is the immense legacy of someone who described photography as “a very warm kiss.”