It was cold and a melancholic atmosphere covered the Berlin Zoo the other afternoon. He walked under the big trees along the leaf-covered paths with the yellow gaze of the tawny owl (misty stream) still stuck in the retina. After entering through the Löwentor, the Lion Gate, with its plinths with stone felines, and seeing the Rhino Pagoda, the zebras and the giraffes in its eastern palace (unfortunately the old bar no longer exists The thirsty flamingo), had entered an aviary where the tawny owl and other large nocturnal birds of prey, including a huge snowy owl, were loose, perched within easy reach. Then I let myself be caught in the amber eye of a tiger that stared at me from its enclosure, a veritable forest in which its orange fur melted into a burst of twilight colors. I had wanted to visit the Berlin Zoo for a long time, a setting in which two things, a priori so different, but which interest me as much as animals and the Second World War, are inextricably mixed.

The zoo, heavily bombed throughout the war, was one of the most terrible scenes of the Battle of Berlin, the fight for the capital at the end of the war, in April 1945, when Soviet troops launched the final attack against the capital of the Third Reich. I have had the image of the zoo combats in my head since I read it when I was 12 years old. The last Stand, by Cornelius Ryan (Destino, 1966), a gift from a German friend of my mother who must have seen something strange in me to choose that book instead of one by Enid Blyton. The fact is that since then I became familiar with General Gotthard Henrici—in charge of the defense of Berlin—and his shabby sheepskin jacket that made his cousin Marshal Von Rundstedt raise his eyebrow, and with the terrible circumstances of the siege and fall of the city, including the wave of rapes of women perpetrated by the Red Army, which Antony Beevor would give a detailed account of many years later in his canonical Berlin, the fall: 1945 (Criticism, 2002).

Cornelius Ryan (1920-1974), who had already written The longest day and then it would light A distant bridge those two great war stories, explained that next to the zoo was the great anti-aircraft defense tower (Flakturm) built in 1941 that also served as a shelter (Zoobunker) against bombing, a hospital and a warehouse to protect the most precious objects from the museums of the city (there were the sculptures of the Pergamon altar, the Treasure of Priam and the bust of Nefertiti, which could have been placed in the zoo’s ostrich house, the Strausenhaus, built in the shape of an Egyptian temple). And there a point of resistance was established that lasted longer than Hitler’s Bunker itself (the massive tower did not disappear until 1948, demolished by the British). The neighboring zoo, which had already suffered greatly from the Allied bombings (a bomb that fell on the Crocodile Hall sent all the reptiles, including the alligator, Black Peter and the Komodo dragon Moritz, flying into the street), it became a battlefield and was devastated, with human and animal corpses everywhere. Of the 4,000 animals in the Berlin Zoo in 1939, only 92 survived the war, including a draft horse (and the paradox is worth it). Russian tanks were firing at the fortress at point-blank range from the Hippo House, where a dead hippopotamus was floating in the water with an unexploded projectile impaled in its body. In the great ape enclosure, a gorilla and a chimpanzee lay dead alongside three SS officers. The gorilla was the popular one Pongo, with two bayonet wounds in the chest. No less than 58 graves of Wehrmacht soldiers were dug in the zoo during the fighting and another 25 German soldiers were buried in a mass grave at the Elephantentor, the Elephant Gate, the main entrance to the park.

Russian soldiers who remained patrolling the zoo—probably in case there were members of the Werwolf—ate several animals, including a bear. The Berliners also used some as proof that elephant meat reached the black market.

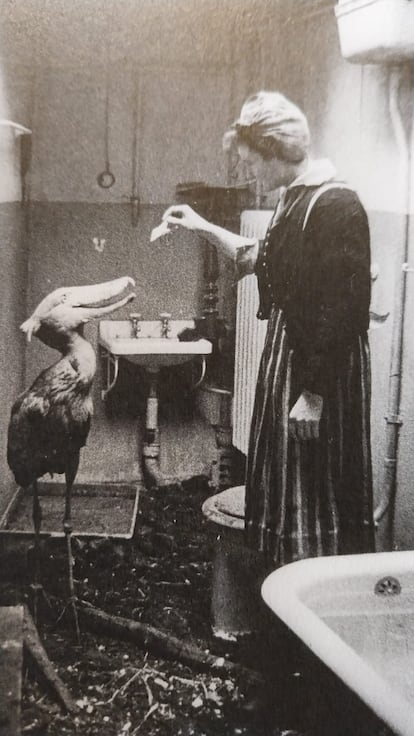

Still, the story that moved me most as a child was the one Ryan told about 83-year-old zookeeper Heinrich Schwartz and his dedication to saving Abu Markubthe rare shoe beak (Balaeniceps rexabu-markub, “father of the shoe”, is what the Sudanese generically call him). Schwarz tried to feed his favorite bird horse meat instead of the unavailable fish, but the huge bird refused to eat and slowly starved to death. Throughout the story of the Battle of Berlin, Ryan returned again and again to the zoo, to Schwartz, and Abu Markubas a counterpoint to the great massacre of the city. On the last page of the book, with the cannons silenced and Berlin surrendered, the old caretaker walked through the terrible devastation of the zoo looking for the missing bird and shouting its name, “Ashes!, Ashes!!” Then: “There was a fluttering, and on the edge of the empty pond stood the strange stork, Abu Markubstanding on one leg and looking at Schwarz. He crossed the empty pond and caught the stork: It’s all over now. Abu Schwarz said. “It’s all over.” And he carried her in his arms.

You can imagine my excitement when, so many years later, walking through the Berlin Zoo as the light faded and thinking about my old book with its red cover that showed the famous photo of the raising of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag, I came across Abu Markub. It was a realistic life-size bronze statue but I caressed it as if it had flown straight from my old dreams.

It was an amazing and exciting afternoon. I pressed my face against that of a jaguar separated only by a glass, I watched a lion silhouetted against a burning sky and the buildings of the Kurfürstendamm, and I photographed a beautiful young Chinese woman who asked me in the Panda Garden. But when you deal with the German past, whether at Wansee or the Tiergarten, you don’t usually get away with it. Near closing time I saw that there was an exhibition on the history of the zoo in the beautiful, orientalizing, reconstructed Antilopen Haus and I went in to see it. The entire zoo is full of memories of its long history (it turned 180 years old on August 1), including statues of famous animals such as Abu Markub and that of Bobby, the charismatic gorilla also immortalized in the park’s logo; another very impressive one of a lion by the sculptor Waldemar Grzimek, cousin of the naturalist Bernhard Grzimek; the enormous stone iguanodont from the Aquarium or a bust of the park’s great promoter (with support from the formidable Humboldt), based on the pheasantry of the Prussian kings in the Tiergarten, Hinrich Lichtenstein; There are also panels between the flower beds and rose gardens with old photos and the destruction caused by the Second World War.

But the exhibition that I mentioned – expanded in the wonderful and very complete official book of the history of the zoo (there is an English edition, Berlin city of animals, by Clemens Maier-Wolthausen, Ch. Links Verlag, 2019)—is especially dedicated to the era of Nazism and makes your hair stand on end. And the Berlin Zoo was very, very Nazi. It’s not that other bad things hadn’t happened before (ethnological exhibitions were held with live human beings, Inuit, Sami, Nubian, Fuegian, Samoan and Sara Kabas), but the Nazification of the zoo was enthusiastic and very complete. From the beginning the staff and staff were enthusiastically gray. Members of the SA and SS had a discount on admission and the director, the ambitious Lutz Heck, who was a member of the Party, an SS contributor and a personal friend of Hermann Goering, put the zoo at the service of the Nazis. The Reich Marshal, whose love for animals was notable, especially for shooting them as Grand Hunter of the Reich, took him under his personal protection. Goering himself gave the park the emperor penguins that the German Expedition to Antarctica gave him in 1939. For its part, the zoo supplied him with the young lions that the second man of the Reich exhibited as pets. Goering was excited by Heck’s Jurassic Park-style program to recreate the extinct aurochs, the large European bovine. The zoo expelled its board members who were Jewish, created a patriotic collection of native and very German animals (geese stood out, by the way, I guess), and hung the “Jews are not welcome” sign even before that anti-Semitic laws were passed and their entry was prohibited. During the war, apart from distributing animals as pets to the army, including submarines and the SS (the rare loris carried by the commander of the Einsatzgruppen exterminator of Massacre, come and seethe shocking film by Elem Klimow, could have been a gift from the Berlin Zoo), zoos in occupied Europe were plundered to expand the Berlin collection, such as Warsaw: the 2017 film tells it very well The house of hope, with the Nazi Heck played by Daniel Brühl. And hundreds of slave workers provided by Albert Speer, especially Polish and French prisoners of war, were used in the facilities.

The subsequent history of the zoo, which remained in West Berlin, is full of less sinister things, such as the active sexual life of the hippopotamus crush, the only survivor in that pool full of corpses from the war and one of the favorite animals of Berliners along with others like the elephant Shanti, Nehru’s gift in 1951, the giraffe Rickreturned to the zoo after being evacuated to Vienna, the alligator Swampy, or recently the famous polar bear Knut and pandas (Berlin is a city that especially loves bears). East Berlin created its own zoo, the successful Tierpark, in 1955, and the two parks entered into competition during the Cold War, including espionage (Tiepark had a Stasi station). After the fall of the Wall, the two zoos have also been unified.

Still, shadows of the past are still present at the Berlin Zoo: the placement in 1984 of a very gently denazified bust of Heck sparked controversy and the statue has not been removed, although an inscription explaining the director’s career during the Third Reich. More arduous has been the fight for reparations for the numerous Jewish shareholders of the zoo who were stripped of their titles by the Nazis and some of whom died in the extermination camps. A commemorative plaque has been dedicated to them and their history appears in the exhibition installed as a necessary reminder in the old heart of the great German zoo.