Nawja Nimri plays a perfidious neoliberal politician, with traces of Isabel Díaz Ayuso and Esperanza Aguirre, who is determined to privatize public healthcare. Borja Luna plays his nemesis: one of the best oncologists in the country who is also a charismatic union leader who fights against the dismantling of healthcare. Things get complicated when the second has to treat the first as a cancer patient. It is the starting point of the series Breathe (Netflix), by Carlos Montero. It has caused people to talk, beyond other artistic considerations, for its explicit position against cuts to the welfare state. Something that some celebrate, as a way to spread the message through popular culture… and that others consider a pamphlet.

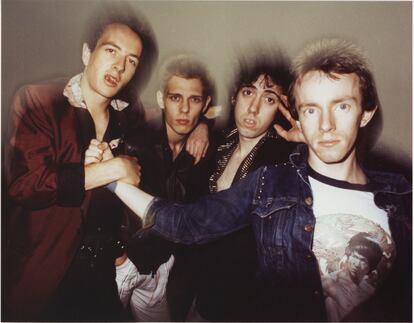

What relationship should cultural products have with politics? Everything is politics, and in political terms a romantic comedy can be interpreted as When Harry Met Sally or a medieval fantasy series like game of thrones. Best-selling writer Sally Rooney declares herself a Marxist, and there is some inadvertent Marxism in her “sad girl literature.” But the political-social has also been explicitly embraced in the history of culture; for example, in the literature of Bertolt Brecht, in the cinema of Ken Loach, Costa-Gavras or Fernando León de Aranoa, in the songs of punk, rap or singer-songwriters, in the poetry of Allen Ginsberg, Adrienne Rich or Gabriel Celaya , in the murals of Diego Rivera. And a very long etcetera.

Ernest Urtasun, Minister of Culture, recently arrived in office, declared that culture is key to the fight against the extreme right. And the extreme right, by the way, sees “cultural Marxism” everywhere, also in culture. To what extent and in what way should films, series or novels embrace certain causes?

Some positions maintain that political commitment should not be the primary driver of creation, but that there must be something else, or something before. The philosopher Javier Gomá, director of the Juan March Foundation, believes that the rationality of cultural works (not to be confused with the cultural industry or cultural policy) is the dignity. That is to say, even if a work is born in a political context or has political consequences or interpretations, “authentic art is born from the love that its author experiences for the dignity and intrinsic perfection of the work he is going to create, anticipated in his mind. “Art enjoys autonomy, it is not a subaltern activity, and the science that studies art is aesthetics, not politics or sociology.” There are those who seek to dissolve cultural products in cultural policy, which Gomá considers a corruption of the essence of art. “I fear that this servitude is one of the symptoms of vulgarity as a general state of contemporary culture. This vulgarity has infected many artists, some of them famous, as well as critics, gallery owners and scholars,” says the philosopher.

The idea of “art for art’s sake” is already intuited in Kant’s philosophy, where beauty is an end in itself, and is taken up in the 19th century by romantic artists and writers, such as Théophile Gautier: creation should not be subject to political, moral or utilitarian purposes. The artist is a very free and indomitable being who only responds to his creative impulses. It is not the same as what would later be thought in the historical avant-garde of the 20th century, strongly politicized, or in the Soviet Union, where art was conceived as an instrument at the service of the Revolution. Totalitarian regimes, including the Nazi regime, have an instrumental vision of culture: they either censor it or use it for their own propaganda purposes. Culture, as a fundamental part of soft power (soft power), was later fruitfully used to build American global hegemony, and in that same construction process is China, the emerging great power, with its cultural products, particularly cinema.

It is not good, as seen so far, to subject the artistic to the political. But where does what is considered pamphleteering begin and what we could call legitimate commitment end? “That does not exist, there is no limit,” responds the philosopher Alberto Santamaría, professor of Art Theory at the University of Salamanca. In that shadowy area he quotes the paintings The surrender of Bredaby Velázquez, or the Guernica by Picasso. Couldn’t they be considered pamphlets? “The pamphleteer,” Santamaría continues, “is usually limited to when a message or idea is too evident in the work, is left unwrapped or is clumsy. But this varies over time. Pamphleteering is not defined in an ahistorical way: it depends on receptions, modifications or artistic forms.”

Political art also does not have to be totally explicit and give everything to the audience, which generates that feeling of indoctrination, but rather it can follow less well-trodden paths: “I think it is not good to ask art and culture for the literality of political messages, because if something characterizes culture, it is that it allows us to move in ambiguity, ambivalence and contradiction. Feeling and thinking opposite things at the same time. That is a great value of art,” says Jazmín Beirak, general director of Cultural Rights of the Ministry of Culture and author of the essay. ungovernable culture (Ariel).

The situation influences the reception of political issues. Before the outbreak of the 2008 crisis, the probability of being branded as an activist increased when pronouncing the word capitalism was considerably higher than once the financial debacle began, when an astonishing percentage of plays, novels, collections of poems or performances They began to feature evil bankers, evicted families, cruel riot police and street protests. For years the crisis hovered over practically everything in the creative panorama, and in a very explicit way. Culture, a reflection of society, varies with its ups and downs, so in good times (if they still exist) commitment tends to diminish.

Sometimes the defense of a cause in a cultural product can be detrimental to that cause, as Sergio del Molino defended in a column published in this newspaper, where he harshly criticized the series. Breathe. For the writer, the pamphlet does not have a necessary negative connotation, it simply denotes a propaganda purpose, as legitimate as any other. The quality of films with an undisguised message, such as Battleship Potemkinde Sergei Eisenstein, o to kill a mockingbirdby Robert Mulligan (based on the novel by Harper Lee). “In art there are no correct postures, only qualities. There are works that ennoble causes: there is no doubt that to kill a mockingbird helped the fight for civil rights in the United States and that artists like Eisenstein gave air and intellectual prestige to communist regimes. When pamphleteering art is good, it helps the cause. When it’s bad, it tears it apart,” says Del Molino.

“It is naive to think that there is a dichotomy between politics and aesthetics,” explains Camil Ungurearu, professor of Political Philosophy at the Pompeu Fabra University and author of Cinema and politics. A quick dive (Tibidabo Ediciones), “art often has an explicit or implicit political dimension that needs to be addressed.” He mentions, for example, the conservative ideology of Walt Disney’s cartoons since the 1950s, the patriarchal reinforcement caused by certain romantic comedies or the expansion of “the social and moral-political imagination” of Pedro Almodóvar’s cinema.

Gorka is too lazy

He good Political art can, therefore, raise awareness and create indignation, although excessive exposure can also undermine that ability to mobilize bodies or minds, becoming a cliché or empty message, in a similar way to internet activism, also known as clicktivismo. We get offended on the couch in front of the Netflix screen, at the exit of the exhibition and during the drinks, in the timeline of social networks; Then we move on to something else and our lives, and the world, continue as always. It is difficult to measure the transformative potential. In societies where there is great emotional polarization, like the ones we live in, culture finds it more difficult to convince because skepticism is widespread and political positions are trenches from which it is rare for anyone to move. In the end, political art remains for the joy and excitement of those already convinced.

Another derived question is how capitalism, which is a mix between a steamroller and a sponge, absorbs and instrumentalizes even the most furious criticism in the market. Any subversive youth style ends up hanging on the mannequins of the textile multinationals and the sounds of the underground that come to destroy everything end up being made profitable by record companies, promoters and platforms. It is very noticeable in the field of plastic arts, where critical art is almost a style like any other, as Santamaría points out in his book Decaffeinated high culture. Low cost situationism and other art scenes at the turn of the century (21st century). It is seen in the frequent scandals at the Arco fair, as in the case of the figure of Franco stuffed in a refrigerator (Always Francoby Eugenio Merino) or in the exhibition of portraits of Catalan “political prisoners” (Political prisonersby Santiago Sierra), which generated a stir in recent years.

“Is it possible to obtain economic profitability from this type of themes?” Santamaría asks about art that criticizes the system. “If so, the paradox is devilish: whoever is criticized (the market) extracts benefit from being criticized. I prefer to think that, even so, the market cannot control all forms of reception. A work of this type cannot work if it is not capable of harboring some hope of emancipation, even a little.” Through commercialized culture, hopes and transformative impulses can still sneak in, especially in this context of political and ecological crisis that generates a generalized feeling of an abolished future. “These are times when the foundations of our communities are questioned and it is especially crucial to have new stories that have a political dimension. We need new political imaginaries, inspiring stories that sharpen the critical spirit, stimulate the senses and emotions, and expand the moral imagination,” says Ungueraru.

Finally, although we tend to judge the politicization of culture by its contents, they are not the only determining factor. Other factors must be taken into account. “Culture has to do with the construction of imaginaries, but it also intervenes in how material affections and ties are configured,” explains Jazmín Beirak. For the essayist, the way in which culture is created is of great importance, how its practice generates community and self-organization through music bands, reading clubs, theater groups, orchestras or choirs. “Culture has a fundamental political dimension, but not only because it transmits or inoculates slogans or slogans, but because it contributes to the articulation of the social fabric,” concludes Beirak.