The Court of Granada has sentenced Santos Boy Jiménez, an antiques dealer from Alagón (Zaragoza), to four years in prison and a fine of 3,650 euros for misappropriation of an 18th century baroque sculpture attributed to José de Mora that, since the 1970s, fifties of the last century, it was located in a cloistered convent in the Granada neighborhood of Realejo. The carving, made of wood and about 1.5 meters high, left the building in April 2018, on the way to Zaragoza, in a Boy Jiménez van. The convent had closed in February of that year and the nuns, according to the ruling, summoned the antique dealer to give them an estimate for the restoration of that piece and some others. They gave her the carving, but as time passed and they did not receive it back, the nuns claimed it. What they received was a “crude copy,” according to the ruling. The convicted man has informed EL PAÍS that he will appeal the sentence.

The antique dealer claims that he paid 10,000 euros to acquire the piece. A few months later, he sold it for 90,000 and the next public news was that it was being offered in New York, where it was located, for 350,000. Once the departure abroad was reported by heritage associations in Granada, the figure was confiscated by the police and among the numerous people involved in the piece’s route from Andalusia to the United States, passing through Alagón, Madrid, London and Maastricht, The only one who knowingly did something illegal was the Zaragoza antique dealer, according to the judges: he kept a sculpture that was not his and deceived the nuns by practically returning a doll. For justice, no one else did anything against the law.

The story begins in the first days of February 2018, when the cloistered convent of Los Angeles closed its doors. After the abbess died and with only three nuns, the order of the Poor Clares established its definitive closure. But closing a convent opened almost five centuries earlier, in 1538, goes beyond pulling the door and leaving. There were dozens and dozens of antiques that, with more or less value, had to be moved to avoid loss and looting. This transfer of belongings took place for the most part between that February and the following July. The nuns had gone to a convent in Estepa and one of them, Sister Josefa Palacios, was appointed pontifical commissioner in charge of an orderly eviction and inventory of the heritage. The truth is that the output of the material was not as orderly and noted which must have been because, months later, some pieces appeared in the Madrid flea market.

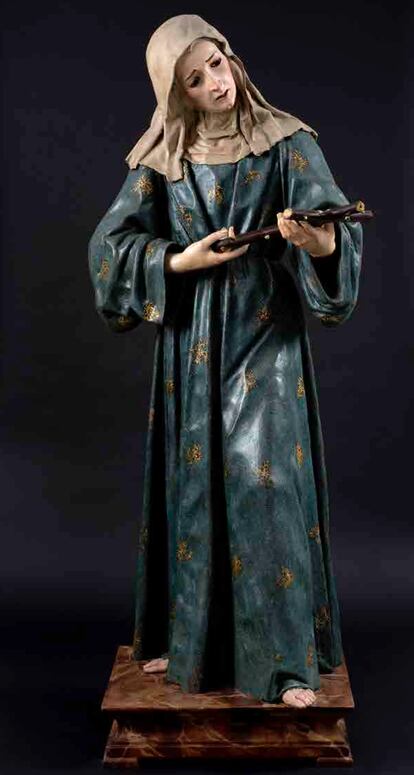

Regarding the sculpture of José de Mora, it is relevant to know that until 2019 it was known under the title of Santa Rosa de Viterbo. That year, the gallery owner Nicolás Cortes—who bought the statue from Boy Jiménez for 90,000 euros in June 2018 and has been acquitted in the trial—published Seven Centuries of Spanish Art). There she already appears as Saint Margaret of Cortona. Although closed, the convent celebrated masses open to the public and the carving was well known to the people of Granada who came. It was near the altar, high up, to its right.

The closure of the convent was published in the media, so it did not go unnoticed by antique dealers, gallery owners and people in that field from all over Spain. More than one passed by and, after paying in cash and leaving quickly, the convent became empty. Some pieces appeared in the Madrid flea market and others, like the then still Santa Rosa de Viterbo, left Granada in Santos Boy Jiménez’s van. This antique dealer admits that he found out, like so many others, about the situation of the convent and traveled to Granada. He took two trips in the van and explains to EL PAÍS that everything was a sale with the nuns’ knowledge. However, they, and now also the sentence, speak of taking this piece—750 kilometers from the convent and another 750 kilometers back—to make a restoration estimate.

From there, the gallery owner Nicolás Cortás bought the image from the antique dealer “without knowledge of its illicit origin,” say the judges. A machinery is then set in motion that in five days obtains an export permit from the Ministry of Culture and ends up with the piece in the Cortés gallery in London. The piece is put on the market for 350,000 dollars (320,000 euros at today’s exchange rate). The sculpture already appears as Saint Margaret and with that name and the documentation it travels from London to Maastrich (Holland) and New York. Nobody wants it for that price and, during its stay in the United States, the history of the work is made public and the gallerist is required to bring it back and hand it over to the police while they investigate who it belongs to and, also, if can be sold abroad.

A central part of that operation is the name change, which is not trivial. The piece is cataloged but, even today, the Andalusian Institute of Historical Heritage, in charge of the protection and research on the historical heritage of Andalusia, maintains the file of this piece in its digital archive under the name Santa Rosa de Viterbo and places it in Steppe. The image on the token is the one we now know as Saint Margaret of Cortona, but, therefore, no one who searched for Saint Margaret of Cortona in archives, the internet or a specialized database would find, in 2018, images or tokens about the object piece of controversy. So that name and image made match We had to look for her in Santa Rosa de Viterbo.

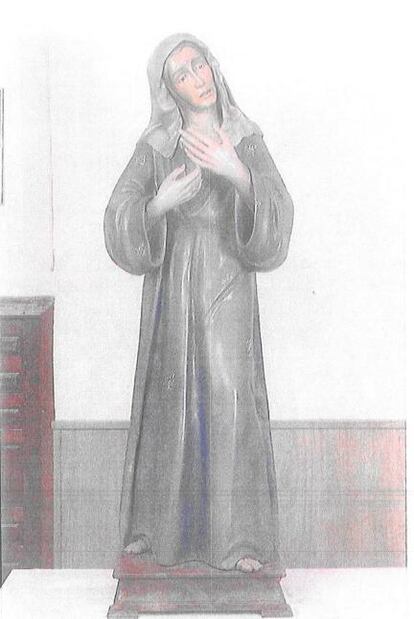

The journey has other moments of interest. For example, when the nuns, according to the judges, ask the Zaragoza antique dealer to return the piece because he took it a long time ago. According to the nuns, something that Santos Boy Jiménez denies, he returned them a copy easily distinguishable by, among other things, the position of his hands, lack of a cross, etc. The truth is that they considered the copy good and did not denounce it until sometime in 2019, as the nuns have acknowledged, when the whole matter of the comings and goings of the piece was already public.

Since January 14, 2020, when the gallery owner delivered the piece to the police, the piece formerly known as Santa Rosa de Viterbo rests in one of the warehouses of the Museum of Fine Arts of Granada, in the Alhambra. Once the judicial process is resolved, the work should leave for its destination, almost certainly the Poor Clares convent in Écija. The convent that they closed in 2018 is now owned by a Buddhist community, which bought it for 2.5 million euros to convert it into a meditation center.

Jesús Villamor Blanco, lawyer at the Ayuela Jiménez firm and defender of Nicolás Cortés, and Laura Sánchez Gaona, Art Law advisor at that firm, highlight: “The court has taken the four main arguments that we put forward to consider that our client did not know in “there is no case that the work could have been stolen.” And they emphasize that Cortés makes public at all times that he is the owner and wants to sell it, so “it does not move in a clandestine environment, but quite the opposite.”

Santos Boy Jiménez, for his part, has been very upset with the fact that the court did not admit a recording in which, according to him, it would be demonstrated that the nuns did not give him the work for a budget, but rather sold it to him. .