The latest issue of Jazz Magazine has a striking cover. In the center, a date: 1959. And a subtitle: “Journey to the heart of the best year in the history of jazz.” It is true that this exaltation is not new, in fact it has a lot of nostalgic cliché, but the French magazine delves into the great protagonists of that prodigious year. As the main figure, it highlights the trumpeter Miles Davis, creator of Kind of Blue, It is usually considered the best-selling jazz album of all time (as a matter of principle, one should be wary of such boasts—without figures—from record companies).

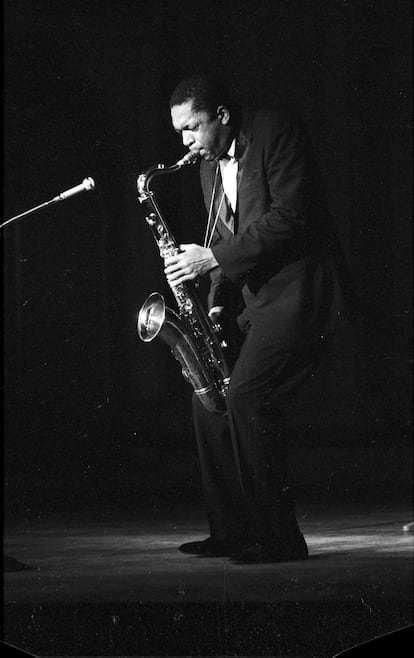

Kind of Blue There was something of a miracle about it: it was done in ten hours, spread over two days in March and April, with no prior rehearsals and minimal input from the trumpeter. Miles’ personal magnetism succeeded in creating a serene, impeccably cool; Even the title seems as colloquial as it is enigmatic, an anticipated answer to those questions about the content of his records that Miles detested. Jazz Magazine The age of the participants stands out, almost all around thirty. That is, with exciting memories of the uprising of bebop, but aware of the risks —Charlie Parker had died in 1955— and willing to try modal jazz. A true dream team: saxophonists John Coltrane (tenor) and Julian Cannonball Adderley (alto), pianists Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Jimmy Cobb.

They would all grow musically in 1959. Miles himself would insist on adapting the second movement of the Aranjuez’s concert, by Joaquín Rodrigo, an audacity that would deeply irritate the Valencian author but that would lead to another groundbreaking album the following year, Sketches of Spain. Coltrane, who had already recorded extensively—as a leader and as a sideman—at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in New Jersey, signed with New York’s Atlantic Records in exchange for a Lincoln Continental sedan and a $7,000-a-year guarantee (about $75,000 today). He wanted a modicum of security: Giant Steps would forget about the standards to play his own songs with superhuman concentration. Coltrane would participate in Cannonball Adderley Quintet in Chicago, contrasting his busy sound with Cannonball’s more earthy expression.

Pianist Bill Evans was more timid than his colleagues. Despite having provided the germ of two of the pieces of Kind of Blue, for his first album in 1959, Everybody Digs Bill Evans, He focused on other people’s pieces, although his delicate solo theme, Peace Piece, has had abundant later recreations, even in the classical universe. Miles’ respect for Evans was such that he did not grumble when he played in Chet, a New York album by his Californian competitor, the handsome Chet Baker.

If Bill Evans was reticent about his talent, there was another pianist happy to find the perfect jazz trio: Canadian Oscar Peterson recorded more than a dozen sparkling LPs in 1959, from A Jazz Portrait of Frank Sinatra a Oscar Peterson Plays Porgy & Bess. Some might wonder if all this production was profitable. Yes, it was: these were quick (=cheap) recordings and, although it was not known at the time, they would have a long commercial life. In addition, the record companies needed to diversify their offering. Rock and roll had lost momentum, with Elvis Presley doing his military service in Germany and Buddy Holly losing his life in a plane (a year later, in 1960, another equally talented singer-guitarist, Eddie Cochran, would die).

Devastated lives

In 1959, there were also devastating deaths in jazz, usually due to alcohol or hard drugs. The sublime saxophonist Lester Young died after a European tour, aged 49. At his funeral, his friend Billie Holiday said that she would be next, and indeed she died four months later, aged 44. Near Paris, Sidney Bechet, a link to the murky origins of jazz in New Orleans, also died. Boris Vian, a novelist, singer and formidable publicist for jazz in France, also died aged 39.

The life of the jazzman o to jazzwoman could be harsh. Thelonious Monk, a fragile-minded pianist and composer, had unpleasant encounters with the police that led to his license being revoked for years. cabaret card, essential for playing in New York clubs. To vindicate his angular talent, he was presented in February 1959 at a university campus with an extensive evening formation from which he extracted The Thelonious Monk Orchestra at Town Hall. Charles Mingus was another troubled genius. Fresh out of Bellevue psychiatric hospital in Manhattan, he assembled an all-star group—on saxophones none other than Booker Ervin and John Handy—that recorded for Atlantic and Columbia. The latter company released Mingus Ah Um, which combined a vigorous carnality with sober recognition of his predecessors: Ellington (Open letter to Duke), Lester Young (Goodbye Pork-pie Hat) y Jelly Roll Morton (Jelly Roll). Equally noteworthy is Fables of Faubus, mocking Orval E. Faubus, the racist governor of Arkansas who opposed the integration of black and white students, forcing President Eisenhower to come out of his slumber and send in federal troops: the famous First Airborne Division. However, Columbia vetoed Mingus’s lyrics and published an instrumental version.

The involvement of jazz in the fight for civil rights was immediate and had abundant manifestations; in 1960 the powerful We Insist!, also known as the Freedom Now Suite, The work of drummer Max Roach, his partner Abbey Lincoln and lyricist Oscar Brown, was received coolly, perhaps because of its wide thematic range—from Southern slavery to apartheid South African—or by musical intensity. In 1959, Ornette Coleman had tested the tolerance of the jazz public, including his own colleagues, with an LP provocatively titled The Shape of Jazz to Come. The form of jazz of the future involved unpredictable improvisations and a strident sound, partly derived from the use of a plastic saxophone.

He announced the upcoming materialization of the movement of free jazz, kick in the shin of formalists like Dave Brubeck, whose witty Take Five would sell millions of copies in later years. It also represented an amendment to the entire hard bop, especially in the variety soul jazz (Jimmy Smith!) or funky, embodied in 1959 by Horace Silver, a pianist with roots in the Cape Verde Islands (Ornette’s astringent approach dispensed with the piano). They said that Silver’s compositions brought tropical exoticism to jazz, but they ignored the fact that that same year two contagious records were released in Brazil: the soundtrack of Orfeo Negro and the first album by João Gilberto. The bossa nova, which, from 1962 onwards, would flood jazz like a tsunami.