On January 28, 1937, the national troops had taken the western area of the capital of Malaga, the Italian fleet imposed itself from the sea and the German bombers were waiting their turn. Norwegian journalist Gerda Grepp knew that Málaga was doomed as soon as she arrived. She found streets in ruins, thousands of refugees. Scarcity of food and abundance of fear. Entire families fled along the road to Almería, where they were massacred in the episode known as The Disband. “One feels like a coward, leaving behind a city in which so many are going to die,” wrote Grepp, the last journalist to leave the Malaga capital before her fall. Tenacious and passionate, she recounted the Civil War in Spain for a year and a half. She did it from the front line, with stays in Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia or Bilbao. The Norwegian journalist also relates it in her biography. On the front, recently published in Spanish by the Malaga publisher Plankton Press.

The reports and family letters written by Grepp, the first Scandinavian journalist to set foot on Spanish soil after the July 17 uprising, are the pillars of the exciting book that also explores her private life. Born in Oslo, the daughter of two totems of Norwegian socialism, Kyrre and Rachel Grepp, her family upbringing and training in Copenhagen and Vienna defined her anti-fascism. A young mother of a boy and a girl, she was convinced that the growing fascist movement, which was then becoming strong in Nazi Germany, had to be fought as soon as possible.

Grepp saw the Spanish Civil War as an opportunity to contribute his grain of sand and, in the process, relate the combat between two ways of seeing the world. “She had an incredible life and felt the obligation to leave her mark, that’s why she took the risk in Spain,” says Marta Koch-Mehrin, director of Plankton Press, which is publishing only her tenth book with this: “We are very interested in recovering women and her “It fit perfectly.”

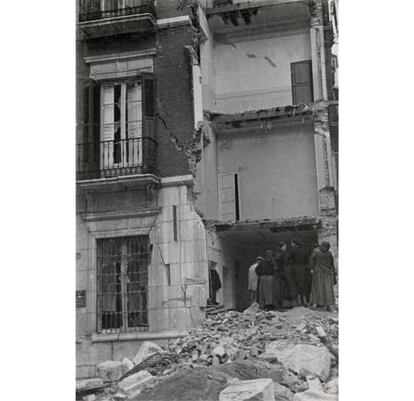

Separated from her husband, Grepp left her children in the care of her mother – a convinced feminist – and traveled to Barcelona in October 1936. Barcelona was the epicenter of the European left and life, like ideas, was bustling in the streets. “The atmosphere is simply wonderful,” Grepp said in a family letter. She wrote four reports for the Norwegian newspaper Arbeiderbladet, also published in Sweden and Denmark in the Social Democrats. He soon knew that he must go to the front. With his international press card in his pocket, at the end of the month he went to Madrid, where he found frenetic military activity. Staying at the Gran Vía hotel, she came face to face with the war and described a city with ration lines, nerves, and soldiers. The population looked at the sky with terror. “Out of nowhere, bombs rained down on Madrid,” she said. She followed the action of the bombers with her colleagues from the Telefónica tower, but also at street level. “A bomb bursts the milk line, explodes against the wall in the middle of the line and kills five women. All the others are hurt,” she wrote.

Grepp was the eyes of the Nordic countries in Spain, with a journalism that was little practiced at the time: he listened to the victims, told the experiences of civilians, looked at the pain. “It focused on the suffering of the weakest,” emphasizes Elisabeth Vislie, who published the biography in Norway in 2016, after delving into the Grepp family archives. “Male journalists had largely reported from the front lines and the trenches. But when the reporters arrived in Spain and saw so much suffering and atrocities, journalism changed. Gerda’s most compelling works deal with the suffering of children and women in war. They are her journalistic legacy,” says Vislie, already retired from journalism. She describes Grepp as part of a generation angry and fearful of fascism. She was also a brave, forward-thinking woman, a convinced socialist, idealist. “She believed that she could contribute to making the world a better place and she worked at it with fervor,” she notes.

Valencia, Malaga and the Basque Country

After a brief rest in his country and some classes to improve his photographic training, in January 1937 he traveled to Valencia, already the seat of an exiled Government. The Civil War occupied the front page of newspapers throughout Europe and she wanted to experience it even more closely: Malaga. Only the Hungarian Arthur Koestler—journalist and also spy, later author of Spanish will—accompanied her. They visited Alfarnate, where the soldiers smiled for their camera four days before that front fell. “They were photos of young men who had never seen a woman wearing pants before,” Vislie recalls in the book. She later tried to get to Marbella and only a miracle saved her from the bombs that afternoon. She left Malaga by instinct. “I felt terribly ashamed and cowardly doing it,” she admitted. She was also the last journalist to leave there.

In Andalusia he had known the lack of control of the Republican army, the lack of means, the hunger of the soldiers. He knew the annihilation of civilians by sea and air on the Almería highway, The Desbandá, while she escaped in an official car. She had a bad time. And on her return to Valencia she suffered the psychological consequences, destroyed, wandering between barricades. She “had a clean look at the war in the sense that she worked with a certain naivety and the photos of her, almost spontaneous, sought naturalness. She understood that in a catastrophe like this none of the sides was up to the task,” says producer José Antonio Hergueta, who has Grepp as the protagonist of two documentaries: Paradise on fire y Caleta Palaceboth nominated for the Goya Awards, with actress Ana del Arco in the role of the Norwegian.

Later she was sent to the front of the Basque Country, where she suffered in the trenches of blood and death. She knew the horror of Guernika through its victims. She went hungry. “The battle of Madrid is like a game and Malaga is like a pleasant getaway compared to what I am experiencing here,” she said honestly in a letter to the American journalist Louis Fischer, with whom she had a close relationship. At the age of 30, on June 14, 1937, she embarked on the Habana heading to the United Kingdom surrounded by children. She was once again the last journalist to leave the city: Bilbao fell just five days later. She then passed through Paris, her work was recognized in numerous international meetings and she hesitated about returning to Spain, until tuberculosis ended her life in 1940, at the age of 33, months after the Nazis occupied Norway. . “There was a long war with the Germans, it was a traumatic period and, perhaps, that was why Gerda’s story had been lost,” says Elisabeth Vislie, whose role has been fundamental in recovering the figure of Grepp.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_