“Hello! In this room there are very modern armchairs, stools and tables,” exclaims a visitor as he turns the corner of the gallery. No one expects to find seemingly common furniture on display at the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum. Some of these pieces belonged to the Huarte Beaumont family, well known in Navarra for their companies and patronage actions. Others were for sale in the iconic Espiral furniture store in the center of San Sebastián, now defunct.

Its design is by the Basque artist Néstor Basterretxea (1924-2014) and follows the Nordic trend of the middle of the last century, although with limitations. “It is noticeable, above all, in the profiles of Huarte’s industries. This structure is the basic element that forces the artist to work on very specific forms during his time in Madrid,” explains the curatorial director of the exhibition, Gilermo Zuaznabar.

This Monday marks the centenary of Basterretxea’s birth and more than twenty Basque institutions are gathering around his figure. Hence, this exhibition about this multifaceted person with a great presence in Euskadi due to his nearly fifty sculptures located in public places. “We have a stereotypical image of him, but he has a very interesting life, in which he touched many disciplines,” admits Zuaznabar during a visit to the gallery itself in conversation with EL PAÍS.

great cartoonist

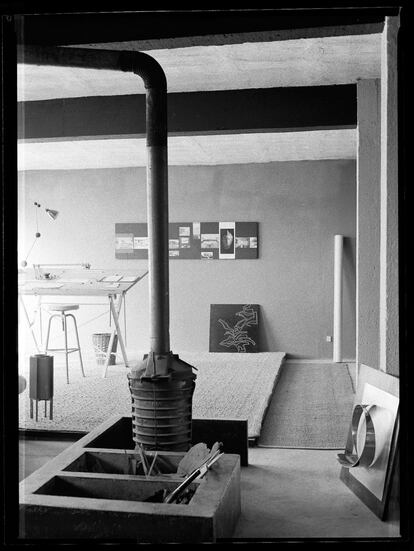

His union with Jorge Oteiza was such that, in 1958, the two artists settled in Irún, in a house-workshop that he himself designed. In that house, not only Basterretxea drew. The floor of the outside porch used to be covered in scribbles. In this case, not pencil, but chalk. His son Gorka Basterretxea and his friends entertained themselves this way when they left school. “It has been a very diverse and plural house. The door was always open,” remembers his descendant. “In addition, Uncle Jorge and Aunt Itziar lived next door—referring to Oteiza and his wife, Itziar Carreño—so you can imagine the constant effervescence of that.” Now, the City Council of the border town is restoring the building, until recently, in ruins.

This sculptor born in Bermeo (Bizkaia) really stood out for his skill with the pencil. The concept of three dimensions on paper still amazes his son. Just as Oteiza molded clay and then translated it into iron, Basterretxea sharpened the charcoal and let himself go. “My father He was a very good draftsman, in fact, he met me or taking a portrait of him in Argentina, where he had to emigrate and earn a living after seeing his desire to study architecture cut short after the outbreak of the Civil War.”

Search for transformation

Its marked nationalist ideology and the Franco dictatorship accentuated this search for a reorganization of society with new forms to generate new values. Zuaznabar points out that this was also happening in other European countries after the Second World War: “Artists conceived of art as a way to reach society not only in a museum, but through everyday objects.” Hence, the catalog of his works includes more furniture, such as a bed base (1965), even cabinet handles and chandeliers (1968) or a chess set (1961).

“Basterretxea cannot be separated from its present,” says the director of Artium Museoa, Beatriz Herráez, by telephone. “He was involved in the social transformation of the political and social scene of Euskadi in the late 60s and early 70s,” she specifies. Her “remarkable work” has had an influence “not only in plastic languages, but in many areas,” she considers the person in charge of the Basque Museum of Contemporary Art.

The chief curator of the Bilbao art gallery adds that Basterretxea placed art within modern movements: “He does it in a way that represents a social transformation. “He identifies the characteristic Basque forms and presents them from absolutely modern and groundbreaking languages.”

Public work

That feeling, added to the influence of Oteiza, introduces the artist to sculpture. “The first public work was a sandstone fountain in Irún (Fuente1969), while the last one was placed in Baiona (Good morning Bayonne, 2014)”, details his son, who is also dedicated to cultural management. However, his most ambitious and emblematic work is Basque cosmogonic series (1972-1975) composed of 18 sculptures, 17 made of oak wood and one bronze.

Basterretxea himself reflected in one of his texts the reason for his projection towards sculpture: “I worked on the long apprenticeship of ordering shapes (…). But now, I strive, out of Basque passion, in (…) a work of introversion into the deepest and most suggestive roots of our people, to interpret with tangible images the ideas implicit in our first tribal gestures.”

Censorship in the Sanctuary of Arantzazu

Along this path, he also came across the Church when he entered the competition for the pictorial decoration of the new Arantzazu basilica. After a year of work, his work was attacked for discrepancies in his avant-garde style. He was not able to finish it until 1984. “It seemed like an atrocity to the hard-line ecclesiastical sector of the time. The whole family was extremely angry,” recalls the youngest of Basterretxea’s four children.

In the mid-70s, the Alava Provincial Council commissioned him to create the objects of worship for the Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Lasarte church. There were, in total, seven liturgical pieces: an altar, two gates, an ambo, a tabernacle and two candelabra.

Activities for the centenary

A few kilometers from this temple, Artium Museoa is a witness to all the work done by Basterrexea. In its documentation center, more than 7,000 pieces are preserved, including drawings, texts, publications and photographs. “The family had the generosity to deposit the artist’s archive,” thanks Herráez in an intense week of preparations for the cultural institution: in a few days, they will inaugurate an exhibition with those archives.

This new exhibition in Vitoria comes after hard work of scanning, cataloging and uploading these documents to a website – soon to be public -. “They are projects, for the most part, unfinished and almost utopian,” describes the director. It will join the one open until the end of May at the Bilbao museum and other events organized by the Etxepare Basque Institute, the Basque Film Library, the San Sebastián Film Festival, the Basque Parliament and several city councils.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_