Jony explains it like this: he was born in Malaga and spoiled in Madrid. His parents were heroinemos, and his mother prostituted himself. He has a memory: when I was little, one day, when he woke up, she “took me from the head and put it in her pussy while I shouted at me:” Thanks to this we eat! ” It wasn’t even true. Almost all the money that entered the house was to buy horseand many times the child had breakfast a glass of water with two teaspoons of sugar.

Jony himself —jonatan Artiñano – in his book himself Thus I ended up living on the street (Penguin, 2025). Many people already know their story because he explained it on YouTube, on Instagram, on Twitch – where almost 400,000 followers have – in their accounts living on the street.

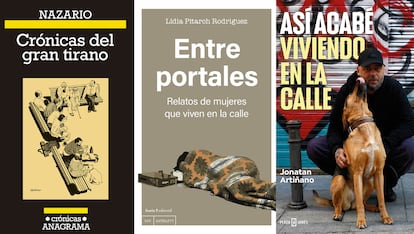

Artiñano has also literally illuminated, in his Streamings– An invisible condition that happens in broad daylight: what it means to live without a roof. In addition to Jonatan’s work, two other publications deal with this topic: Chronicles of the great tyrantfrom Nazario (Anagrama, 2025) and Between portalsby Lídia Pitarch (Icaria, 2025). From different angles, the three books talk about people who live in the weather, a problem that is omnipresent and few want to see. A mirror that returns an image that costs a lot to look.

Jony’s story seemed to improve when his grandmother got her custody and went to live with her. A noon prepared rice to the Cuban and Jony already seemed like a dish so excellent that it spent the following months asking for the same to eat.

But that new homemade paradise was a mirage. The boy was not going well. They were expelled from school and then went to an institute where there was competition to demonstrate who was the worst. “It was exhausting,” he acknowledges now. He walked with the worst companies and began to do things I noticed that I didn’t fit anywhere. Just playing soccer, goalkeeper, felt the appreciation of others.

It was worse. He tried the pills, the cocaine, and began selling them to pay their consumption, until he stepped on the jail. When leaving a mason for a time, and with his first salary the cassette was bought Great plans, of the Violent Poets Club. He also earned a living looking and trading snails for the markets, riding sofas and selling joints prepared by the campus of the Complutense University.

He went back to party and returned the farlopa. He got so much that he was going to catch where he was needed with his Opel Calibra Green Bottle. He returned to jail and when he left he wanted to try his luck in Buenos Aires. But it could not be either. He arrived back in Spain with one hand in front and another behind. He spent a few weeks feeding on what he found in the garbage cubes of Barajas airport, until he ended up living in a Bank of Paseo del Prado.

It was like that seven years, between streets, parks and placitas of Madrid, looking for what to eat, how to wash yourself, where to take refuge from cold, rain or heat, where to keep your things, where you can rest or sleep. Until he managed to stop consuming and have a stable life.

Cigarettes and sardines

The painter, cartoonist and writer Nazario Luque, known as Nazario, had years ago that from the top of his house, in the Plaza Real de Barcelona, who photographed and drew continuously, he saw a group of homeless people who survived between banks, corners and recesses, many times surrounded by neighbors and tourists who pretended not to see them.

He did not look at them when he stumbled upon them, on the street. I was afraid to establish some type of link, “but a glass wall cracks as soon as there is contact with the eyes,” he writes in Chronicles of the great tyrant.

In his case he happened tomorrow, before a greeting. When asked, he explained that he was going to the Boquería market for sardines to batter. Then the group, led by Mich, broke to speak, as in dreams, the taste of that delicacy. Nazario continued on his way, but after buying, cooking, eating and siestear at home, he decided to cook another handful of Fishinglower them to the square and distribute them among the group.

From then on, every day he took food: sepia with potatoes, caldoso rice, meatballs, sauce, sausages with sausage. Something similar to a distant friendship arose, each according to their own interest. For the group, Nazario became the “cloth of tears, cook and pagan philanthropist,” he says, while for himself the relationship meant “a work, a company, a heat space,” he says. Nazario has friends and many acquaintances, pear that was different. Since Alejandro, his life partner for decades, had died, felt “as a dog abandoned in a gutter,” he details in the book.

In those wanderings, Nazario discovers in Mich – the tyrant of the title – a character worthy of Conrad. “Adventurer, offender, expressing, capricious, distrustful, envious, ramming, emboucatory, zalamero, busy, indiscreet, liance, revenge, charming or seductive,” he writes.

And that his greatest fantasy is to have a room for him alone and get a prosthesis for his amputated leg, a poorly sewn stump that “looked like a brunette or a leftover,” according to the Sevillian-Barcelona artist, author of comics like Anarcoma o San Repite a piranhas.

In the dining room of his house, in conversation about his book, Nazario recounts: “I was with them, helping them something like almost four years. At first, Fernanda, my neighbor, told me: ‘Oh, Nazario, how crazy you are!’ And looking out the window that gives to the Plaza Real, seems to miss them. “I more than speaking. The daily life of the Underground cartoonist.

In those comings and goings, with food bags and táperes, Nazario met others who, among blankets, cigarettes and tetrabriks of bad wine, between stories of diseases and thefts, survived in the street. People as a Christian The Frenchthat torea His labrador dog for joy of tourists, who thus threw some coins. Or like Helga, an alcoholic and flirtatious German who loved to dance, who sometimes remembered that he had robbed everything he had years ago, and that, once, at night, he had terrifying nightmares.

A lot of stereotype

The situation of women in the street is much harder if possible. In Between portalsPitch Lídia, Doctor of Global Law and Human Security and Sergeant of the Urban Guard in Barcelona, weaves a fiction of five different women – Lili, Gina, Elisa, Luz and Ary – made of pieces from a fortnight of real women that she met.

Homeless, women normally adopt three different roles to survive, according to Pitarch: some try to go free, go unnoticed and flee from the groups, others adopt an attitude of vulnerability and search for protection, and others face the groups as they can.

Because surviving is very difficult: in his book he details that on the street 10 or 20% of homeless people are women, and that the violence they suffer can be atrocious, reaching 90% of them. That in a very hard situation: in homeless people, mortality is three or four times higher than that of the general population, and life expectancy does not exceed 53 years.

The problem is that the loss of housing and life in general in the city is leading to a dramatic increase of people who end up moving, precisely, between portals: in Barcelona there are 1,250 people in the street (90% more than in 2008); in London almost 12,000 (an increase of more than 100% compared to 2011), and in Los Angeles, 46,000.

“There are people who believe are like that because they don’t accept help, because they have looked for it or because what they do is steal. There is a lot of myth, a lot of stereotype,” says Pitarch. “And from the outside, those people are divided a bit between ‘the poor poor and the good poor’, according to what they are asked, or not,” he explains.

Pitarch coincides with Nazario’s vision: it is difficult to look straight ahead and have empathy with such a problem. “More than I hate, I would say that there is fear of the poor. There is sensitivity to the people who suffer, but with those who are far, not with those in front of your portal,” he reflects on the phone.

His investigations have concluded that many times young women end up living in the street because they have lost along the way in an identity search that has gone wrong. There are bad habits, there is violence, and many times they have broken bridges with their family. In his work, Pitarch confirms that there are girls who agree to repeat the impact of the typical angan phrase at home “If you leave, you don’t need to come back!”, Take it literally. “Sometimes, when we find them living on the street and tell them to warn their family, they tell us that they don’t want their mothers to see them like this,” says Pitarch.

The worst is the feeling of loneliness, of helplessness, that not to matter to anyone, Jony confesses. “One of the things that most hurt people in the street is the mental part. We all need others, their approval, a motivation to follow,” he says.

But nothing is easy, and addressing problems is like a complex issue. “Some only need a push, others instead have serious psychiatric problems, or a chronification of drug use, brutal lack of self -esteem or a very severe alcoholism … and each one needs a different process,”.

He recovered, and now he works from riderdistributing food between streets and avenues. He feels very committed to that community, and between delivery and delivery, confesses that they are planning formulas to avoid the exploitation of foreign work.

Despite the lived inclement, Jony ends the conversation with a light impression: the generosity of many people. “There are people who are for you. It gives you clothes, it gives you food, it takes care of you. That helps a lot at certain times. The truth, I did not expect them to empathize with me,” he says, and then hangs the phone.

“When you suffer like us, the worst thing is to lose dignity. Once I read a poet. It would be Italian, perhaps Russian. I just ask for a little beauty (Editions B, 2016), a chronicle about a group of homeless people in Barcelona, written by the reporter Bru Rovira. “Sometimes you look like a priest, vittorio, a monsignor”, He replies in the book – Joint, half seriously – Rovira. And laugh together.