Commander Román Ingunza traveled in early 1922 one of the British camps that he had gone to all types of military material used by the allies during World War I, when he ran into listening devices that caught his attention. He asked what they served exactly and how they were used and nobody knew how to explain it to him, so, although it is not clear that the commander knew, he bought them at a very low price. And it was not the only similar case, Brigade General Juan Avilés Arnau, his boss and that of the entire commission commissioned by those dates by the Spanish government to tour Europe in search of the gangs that the end of the great war They had left behind in the form of military engineering. “It should not be surprised, because to such camps or deposits almost all the material, in its infinite varieties, established on the fronts and it was less impossible to keep personal expert in all branches of the military technique,” Aviles explains On the foot of one of the three articles he published in the magazine Memorial of Engineers in the summer of 1923.

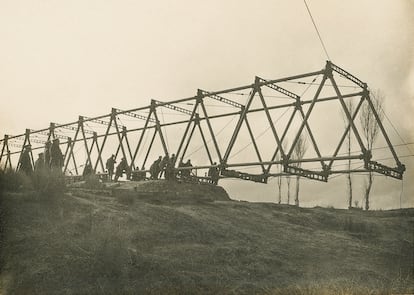

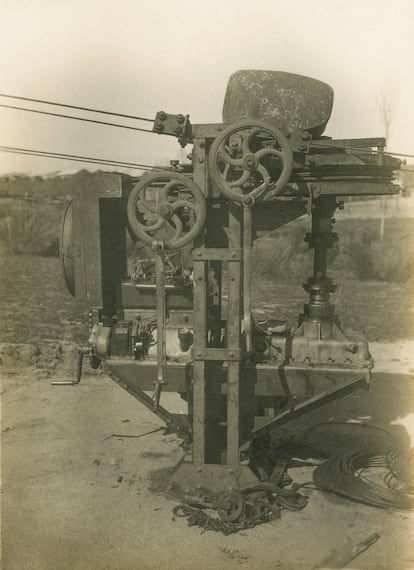

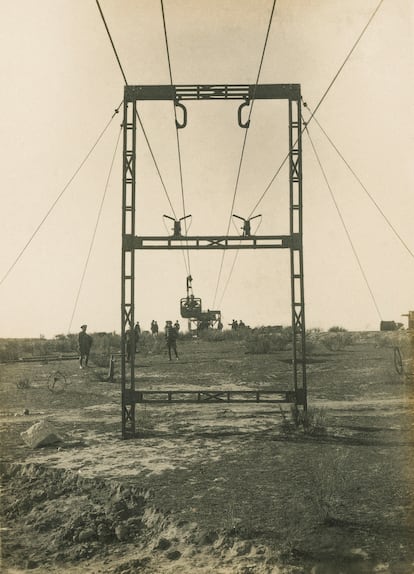

In them, it details the entire process that, after the purchase among others of phones and mobile bridges, flamethrowers, locomotives, all kinds of radio appliances and even a weather station, was completed with an experimental demonstration of use in the Retamares polygon, to The outskirts of Madrid, which lasted for six months. Now, 65 photographs taken those days to document the works have been restored and digitized by the Lucio Gil Fagoaga Foundation, which retains the legacy of the Valencian intellectual in its hometown, Requena.

Spain, which had remained neutral during World War I and whose army was not even among the most modern and best gifted, decided to take the opportunity to get some of the advances that had proliferated during the brutal contest. Thus, the commission headed by General Aviles had the commission to find and acquire material that was unknown until that moment, or that was not manufactured in Spain or that, even manufactured here, could be purchased “at incomparably lower prices”. Everyone they could buy with about 10 million pesetas, the equivalent more or less – according to the reference currency taken to make the estimate – between 18 and 22 million euros today, which does not seem much, having in He says that the objective, beyond the novelty, was to get “sufficient amount to give all” the troops. “Above all those considerations and others less important, the unwavering decision of buying cheap,” Aviles insists.

They didn’t have it too easy. First, because the true bargains had ended long ago, because the war concluded at the end of 1918: “The best time to buy material abroad was that understood since June 1919 to December 1920,” Aviles explains. But also because they had to make their way through a cloud of manufacturers, governments and intermediaries, which demanded a lot , they presented and pondered others, exaggerating their usefulness, and stubbornly raised prices. ” Even so, they achieved in their trips to England, France, Belgium, Holland, Germany and Italy a sufficient amount and variety – the articles do not give exact figures – to leave the promoters of the project satisfied. English blades to 37 cents the unit, 2,000 thermal deposits (thermos) of 14 liters to four pesetas each, new surgical cases to “the sixth part or less of its normal value …”. In the end, in fact, the purchase was not the most difficult, but the transport of devices that were not always in the promised conditions and the assembly of the thousands and thousands of pieces and components that had to reensate for its implementation.

Numerous foreign specialists moved to retamares to lend a hand – a Italian monter for the phones, another German for the steam shovel, a Frenchman for the excavators – although it was not possible in all cases, so it was also much necessary Imagination, especially when a key component was missing that had to be replaced with what could. But the big problem was that those in charge of transport, outside the commission, were carried as they seemed good (some key pieces were stuck for months in the port of Santander) and, once in Madrid, they piled them on the roads and Explanades of the Retamares polygon as God made them understand. Only to order the material of the phones a long month was needed. The railroad, which had to help in the works and serve to try the acquired locomotives, was not complete up to five months after the mission began because the viaduct beams had arrived on the first trips and had been buried under everything that had come later: “(…) were in the immediate esplanades and fields below almost all the material, because of having reached retamares long before the demonstration began.”

To complete the image, I now propose that they stop for a moment to think about all those men – 140 soldiers began, which soon became 250 and reached 400 – that, in the middle of the winter – the work began in October 1922 and It ended on the last day of March 1923 -, they see that, in addition to all that, a good part of the roads have been unused by the rains, frost and the trajín of some trucks loaded to the top for some clues that were made thinking of animal traction vehicles. And, then, as if that were not enough, “the sewers of the toilets of the troop pavilions refused to work,” says Aviles.

Thus, it is not strange that the general celebrated again and again in his articles which considers the success of some works that escaped, in large part, in view of visitors who arrived at the last moment to see how the flamethrowers or lo resistant that were the newly bought transportable bridges. Visitors among which were the then Minister of War, Niceto Alcalá Zamora, or King Alfonso XIII. “Despite the glacial temperature and hurricane wind, mixed with snowflakes, which made the stay in retamares very unpleasant, SM saw everything, he learned everything, asked numerous questions, captivated us with his appropriate observations and did not spare The praise, issuing concepts of affection and applause that the body will never thank you enough demonstration, ”writes the aviles.

Born in Tarragona in 1864, this was not the first technical assignment of this type he received, as he had participated in different commissions on the study of telegraphic networks, architecture and railway traces. Although it was probably the largest, taking into account, in any case, the modesty of an army that suffered a secular lack of resources. A few months after the demonstration, coinciding precisely with the publication of the last of its articles in the Engineering Memorial In September 1923, the coup d’etat of Primo de Rivera arrived, who, among other things, appointed Juan Avilés Mayor of Valencia.

And perhaps this was his connection with Lucio Gil Fagoaga, one of the pioneers of the studies of experimental psychology in Spain, and among whose papers there is a thick photographic album that, under the title Army engineers. Experimental demonstration. 1922-1923is dedicated on the first page. “The dedication is not signed, but we deduce that the gift can be from Juan Avilés,” says the Foundation Archive, Álvaro Ibáñez Solaz. He was the one who located the file in 2018, when he started the works to catalog the documentary legacy of the intellectual requenense. Thanks to a grant from the Ministry of Culture, Rosina Herrera has restored the images and María Ángeles Hervás, of invisible Photo Lab, has digitized them, and the Foundation will try to make them accessible to the public in the future, along with other archival treasures that have gone appearing among the papers that the institution keeps.