A window of the stay at sea, the other two to the urban plot of El Cabanyal. There, in an apartment in the old fishing neighborhood of Valencia, the name of the Italian Umberto Eco is invoked in a hot afternoon of early summer. Campecheanía, scholarship and semi -teaching teaching The name of the roseas the letter that helped a young Argentina to save themselves from the dictatorship of her country or her criticism of the “Fathistas left left ”.

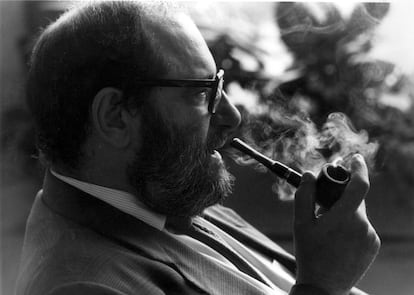

Lucrecia Escudero was that young woman. Today this Argentine semiologist is 75 years old and has the singing voice with its caudalous speech. Discipula and great friend of the Italian intellectual and writer, one of the most influential of the last third of the twentieth century, who died at 84 in February 2016, stars in a new book. His memories, his vital experience and his relationship with him professor turn Umberto Eco (declassified). Salvation semioticsof the journalist and writer Mayte Aparisi Cabrera. Edited by Jot Down, its publication is scheduled for the first quarter of 2026, coinciding with the tenth anniversary of the death of the progressive and anti -fascist intellectual. In his will, Eco expressed his desire that no tribute or symposium or academic act was taxed until at least 10 years of his death. Therefore, an avalanche of news is expected.

Umberto Eco (Declasified) It has the peculiarity of having initially gestated in the Cabanyal – without any link con The professor who taught doctrine from the University of Bologna -, with interviews also in Paris, the two current residences of Lucrecia Escudero, and to approach the most human profile of the author and also his personal and political involvement.

“Umberto saved my life and not only on the intellectual plane,” says Escudero, sitting on the floor of El Cabanyal of the also semiologist Cristina Peñamarín, emeritus professor of the Complutense of Madrid, whose testimony is also included in the trial. Both are friends since 1976, when they agreed on the seminar that echoed in Bologna. They maintained a personal and academic relationship with him for the rest of his life and now they have bought two homes to spend seasons in the Valencian neighborhood, which the Argentine editor based in Paris Carlos Schmerkin discovered.

Retired professor who taught at the universities of Lille (France), Córdoba (Argentina) and La Sorbonona Nueva-París 3 (France), Escudero explains that being a young woman answering at the University of Rosario (Argentina), very active and defender of human rights, she decided to write to echo to ask if she could study with him. In that 1976 it was already an authority in the academic field, but not yet the celebrity that would become years later with the publication of The name of the rose, In 1980. She had been impacted after analyzing her influential essays in the faculty Apocalyptic and integrated y Open work.

Disappearance of students

Those were the years of the crimes of the paramilitaries in Argentina, of the Triple A, of the subsequent dictatorship of the military (between 1976 and 1983) and the insurgency of the Montonera left. The disappearance began to be common, above all, “of students and workers.” “Many of them of philosophy and letters, like me, some very close to me,” says Escudero. “Then I write a letter to Umberto, as who writes to Santa Claus. I was a good student, but it was not waiting for me to turn the miracle at the same time, at a few weeks General Semiotics Treaty dedicated, ”he recalls.

With this credential, Escudero was presented to the scholarships granted (and granted) the Italian Institute of Culture, an organism assigned to the Italian Embassy in Argentina, to study in the transalpine country, especially aimed at the very large population with Italian ancestry. He won it. Fifty years later, the semiologist still gets excited to remember how she breathed relieved and exploded in applause when the plane took off with numerous students on board, leaving their country behind.

“I lived the trip as a release. It is true that some of the students who also traveled did not have the problem of militancy and repression or did not live it closely, but I did, and not just me,” explains Escudero. Argentina tells in the book of Aparisi Cabrera that in its suitcase kept newspaper cuts in which lists of names of people killed in military clashes in Argentina appeared, with a single destination: Amnesty International. “Umberto, years later, recognized me that when he read my letter he perceived that I was in danger,” he recalls. This was also transmitted by the writer to Patrizia Magri, who was his right hand.

Escudero recalls that in the first meeting he held with the intellectual in Bologna, he already showed him his naturalness and complicity, inviting him to eat a pizza and trusting his satisfaction, although also a certain fear: “He had just bought a ruined convent in the middle of the mountain, and as he was married to a very strict German woman, Renate Ramge, he did not know how to tell him.”

The convent

The convent played an outstanding role in the writing process of The name of the rosemedieval detective plot novel and compendium of cultist references that was very well received by critics, a part of which, however, it distanced itself when it became a planetary popular success, with dozens of millions (half a hundred according to some estimates) of copies sold. Last April, the Teatro de la Scala de Milan premiered the operatic version, composed of Francesco Filidei, which will also be represented in the Paris Opera.

All this is spoken in the book of Aparisi Cabrera, which presents the most unknown and close face of Eco in a research work that rescues the oral memory of some of its main disciples, with special attention to its link with Argentina.

The book includes the Escudero meeting in 1990 with an Italian diplomat at the Italian Institute of Culture of Paris. He told him that in the entity “they were aware that with the scholarships granted during the lead years” they were helping to save young Argentines.

In any case, what was not on the part of the Institute of Culture of Italy in Argentina was an organized operation or had anything to do with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, according to the diplomat Enrico Calamai, in telephone conversation with the country from his home in Rome, reports Federico Rivas Molina From Buenos Aires.

“It may be that the director of the Institute helped, but as something personal or that Eco wrote to the Foreign Ministry in Rome,” says the 80 -year -old diplomat, who was working those years at the Italian embassy in the Argentine capital. Previously, Calamai had served as ViceCónsul in Santiago in 1973, a position from which he helped and protected hundreds of Chileans who entered the Italian embassy fleeing from the Pinochet coup d’etat.

In the Italian Institute of Buenos Aires “there was a commission composed of Italian and Argentine officials, who validated the candidacies.” “If the Italian part insisted, the candidacy could happen. In the event that it would have been a well -known guerrilla, it would have been very difficult. There were also many people who were in danger, who had left the organizations and was not yet indicated,” he adds.

The psychoanalyst Cristina Canzio, a friend of Escudero, met Calamei in Buenos Aires, before being also a scholarship in Italy. His only motivation was to study in Florence with Graziella Magherini, the psychiatrist who coined in 1979 the “Stendhal” O “Florence Syndrome”, which refers to a psychosomatic disorder caused by exposure to works of art. His house in the Italian city was a place of passage and contact of some Argentines fleeing the dictatorship in those years, he points on the phone.

Now, Cabanyal is becoming a meeting place with new neighbors. There, Escudero is fixing a ground floor on one of the streets that retain popular architecture (eclectic, modernist, humble) from a neighborhood that went from abandonment and threat of the piqueta to be fashionable. From there he summons the teacher and friend who “changed the chip” and made her see that she “had been a fascista left left. ”Eco questioned the spill of blood from the struggle of the Montoneros and the revolutionary Peronists of the 70s, whom he compared with the Red Brigades of Italy, who murdered Aldo Moro, truncating the possibility of implementing the historical commitment advocated by the leader of the Berlinguer PCI to reach power in alliance with the democratic democratic The great ambitionrecently released in Spain.