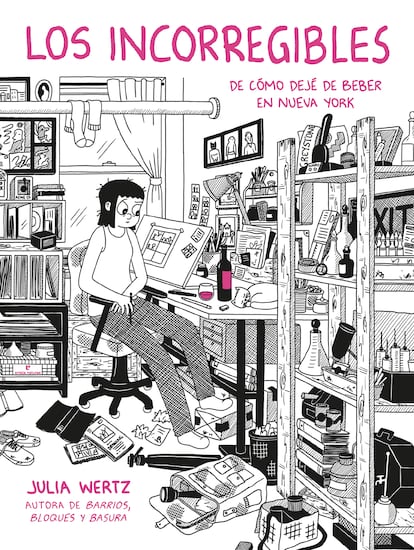

This book is a gift. It is told to us by its author who, in just over a decade, has gone from being excited to being overwhelmed by New York. She has gone from accepting her elitism to learning to make a living and from accepting the difficulty of living there to getting to know the city by getting to know herself. Thus, after signing the priceless Neighborhoods, blocks and garbage (Errata Naturae), Julia Wertz (San Francisco, 41 years old) has once again painstakingly drawn New York. He has walked its streets, investigated its urban legends, delved into the little stories, observed its details, lived its miseries, breathed its greatness. And he has drawn all that. Still, even if his new comic is full of architecture, the gift in this latest journey is inside. Inside. Not only in the few meters of his bare house. Above all, on the journey towards his head, his fears, his refuges, his self-deceptions. And his addiction.

The incorrigible It is a memoir of how Wertz, at thirty years old, went from drinking three bottles of wine a day to getting out of that hole. It is a very serious comic that, with large doses of humor and greater humanity, tells how he stopped drinking in New York. It is important where and how it happened: it was in a wonderful city. I was alone. And that is a double lesson: nothing is just one thing.

That’s why where he stopped drinking is not a coincidence, it is precisely where he started to do it uncontrollably. Where he felt the vertigo of possibilities and the rawness of loneliness to which an ambition can lead.

Wertz’s process of self-inquiry has a setting, Manhattan, that simultaneously oppresses and heals. That is, perhaps, the greatest message of the comic, a memory that serves for any type of harmful attachment: excessive attachment to work, to brands, to drugs, to money, to sex, to gambling, to even unconditional affection. , to almost any distraction that prevents us from the obligation to look at ourselves, observe ourselves and learn to know ourselves. And to accept us as a prior step to any possible improvement.

The exterior of Manhattan offers, it is true, a notable contrast to the mental closure. We are not talking about someone who has lost everything. We are talking about someone obsessed to the point of obfuscation, by his vocation, by his work. That is, the mind, consciousness, the world and another life in this one.

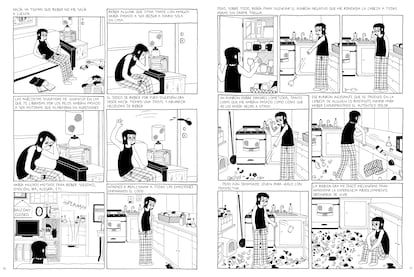

The book begins without tricks or makeup: Julia has just turned 30 years old. He is in Puerto Rico, on the island of Vieques to celebrate. And his car goes down an embankment. At 26 he had already been diagnosed with stopping drinking if he didn’t want to die at 30. On his way out he passed by the liquor store.

She told herself that drinking focused her on work, that it helped her by keeping her away from the problems of the world. And yet, every Monday I decided to stop drinking. But it failed. Anything: a noise that didn’t let her sleep, celebrating two days of abstinence, what Wertz then proposes with her comic is what it makes us see. And what it takes her to see is the size of her home. Its conditions (lack of light, air and proper sanitation). But also the other side: the place where that home allows you to live. The result, I have said, is a double journey, meticulously drawn, nakedly narrated. And with huge doses of humor. Don’t miss it.