In the 1920s, the Palace of the Jewish banker Franz von Mendelssohn, in the lush Grunewald neighborhood, was an outstanding center of the cultural life of Berlin. The niece grandson of the composer Felix Mendelssohn organized there veins of chamber music with renowned pianists such as Artur Schnabel and Edwin Fischer, as well as with famous music fond of music, including Max Planck and Albert Einstein. Mendelssohn & Co. Bank partner, Franz had a valuable collection of old instruments, among which the violin stood out stradivarius Mendelssohn of 1709, who gave his daughter, violinist Lilli von Mendelssohn-Bohnke. She interpreted it in the family quartet with her father and her husband, the composer and violist Emil Bohnke.

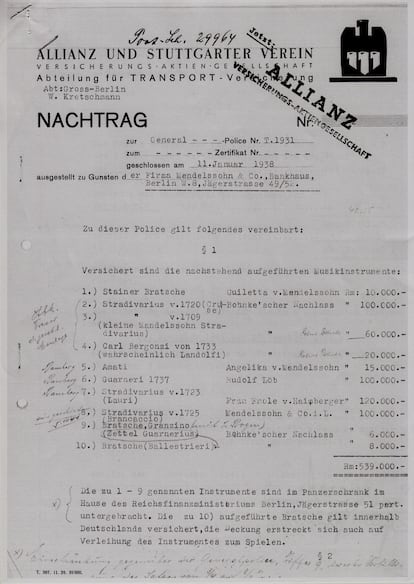

A tragic car accident ended the life of Lilli and Emil in May 1928, leaving three young children. After the misfortune, Franz deposited the instrument in a security box of his own bank, after obtaining an authenticity certificate in 1930. The arrival of the Nazis to power in 1933, their death two years later and the liquidation of the bank, considered a Jewish business by the third Reich, made the violin end at the former headquarters of the Deutsche Bank in Mauersrasse. Apparently, from there he was stolen in 1945 by the Soviet Occupation Forces, although it is also possible that he had been stolen by the Nazis before the fall of Berlin.

This valuable violin has been recently located in Japan, although dated in 1707 and renamed as Stella. A preliminary report prepared by the expert Carla Shapreau, of the Institute of European Studies of the University of California, Berkeley, and disseminated through the website of her project dedicated to the restitution of the musical heritage looted during the Nazi era in Europe, has revealed another fascinating story about a stradivarius plundered during the third Reich.

The intrigue could evoke scenes from the famous François Girard movie The red violin. However, there are studies on the Nazi musical plunder, together with well -documented stories of robberies, sales and reappeARditions of stradivariusthat have nurtured the plot of several novels. It is already a classic Willem de Vries about the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg musical cell, the Nazi command in charge of seizing heritage and eliminating Jewish culture. For its part, the monograph Stradivariusby Toby Faber, combines a pleasant narrative about the life of Antonio Stradivari with the adventures of five of his violins and a cello. As for fiction, Planet has just published the most recent novel on the subject, written by Alejandro G. Roemmers, who starts from the real murder in 2021 of the Lutier Bernard von Bredow and his daughter in Paraguay to build a police and historical story, with Nazi background, around the alleged “last stradivarius”.

Better documented, although literally unequal, is Yoacono’s novel, translated by Duomo Ediciones as Goebbels violin (Le Stradiva-Rius of Goebbels in the French original). The story focuses on the gift that the Nazi propaganda minister made in 1943 the young Japanese violinist Nejiko Suwa: an instrument stolen from a French Jew in a concentration camp. This real story was narrated by Shareau herself in The New York Times In 2012, as an introduction to its ambitious project for the recovery of musical treasures looted by the Nazis, a much less studied area than the plundering of artistic treasures.

Shareau’s article clearly showed the difficulties of this type of studies. The scarcity of documents and the little collaboration of the owners generates controversies and multiple obstacles to research. In fact, the violin given by Goebbels is today owned by Suwa’s nephew, who has never wanted to reveal the characteristics of this doubtful stradivarius of 1722. its results in relation to the Mendelssohn From 1709 they have been very different, since in this case the written and photographic documentation abounds, allowing unequivocal conclusions.

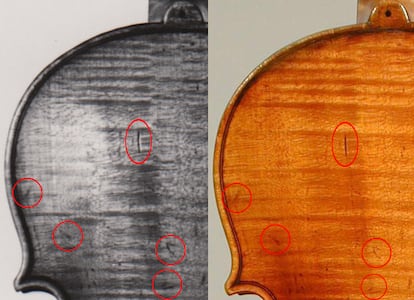

“In June 2024 I discovered the whereabouts of that stradivarius stolen thanks to a track that indicated that the violin could be found in Japan, ”explains Shapreau, who has answered all the questions about his research to El País by email. First he tracked the website without success in search of an instrument of 1709 known as Mendelssohn. Then he compared a black and white photograph taken in 1930, as part of the certificate of authenticity, with all the specimens of violins stradivarius preserved in Japan. It was then that he found surprising coincidences between the brands and scratches that appeared in that image and those of a stradivarius of 1707 called Stella. This instrument had been exposed in 2018 with another 20 stradivarius in the Mori Arts Center Gallery of Tokyo and was owned by the violinist Eijin Nimura.

The story continues with the investigation of the past of the stradivarius Stella of 1707. The first reference to this instrument appears in Paris in 1995, when a Russian violinist took him to the famous Lutier Bernard Sabatier store, on Rue de Rome, to sell it. As the musician said – whose name has never been revealed – had bought it in 1953 to a German merchant in Moscow. Sabatier authenticated the violin in London with the help of the renowned expert Charles Beare, who determined that he had been manufactured in Cremona, between 1705 and 1710, under the supervision of Antonio Stradivari and with the participation of his son Omobono. The manual calligraphy of the label stuck inside prevented whether the date corresponded to 1707 or 1709. Subsequently, the violin passed through two owners and, in 2000, was auctioned in the prestigious Tarisio house in New York, where Jason Price studied and photographed him.

Price also responded to El País by email and confirmed the recent finding of Shareau: the stradivarius Stella and the Mendelssohn They are, in reality, the same instrument. This expert is not only the founder and director of Tarisio, but also the head of the Cozio Archive, which has the most complete database of rope instruments and ancient arches. Interestingly, the name of Stella It appears for the first time in a report dated March 31, 2005, in which its origin is detailed – “he was in possession of a noble family who lives in Holland since the time of the French Revolution” – and the origin of his nickname: an ancestor called him Stella because its sound “shone like a star.”

Shareau has confirmed that this document is false. In the last update of your report, dated August 7, the two responsible cited denied their authorship. Both the Lutier Bernard Sabatier – whose name appears as a signatory – and the Austrian merchant Dietmar Machold – whose letterhead appears in the brief – today reject the veracity of that declaration of origin of the stradivarius Stella. However, the instrument was sold in 2005 to the Japanese violinist Eijin Nimura, an artist for the Peace of UNESCO, who has never wanted to collaborate with this research or respond to this newspaper.

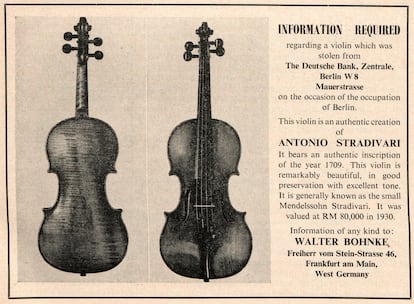

The heirs of the Mendelsso-Bohnke family have always struggled to recover this instrument plundered during Nazism. According to Shapreau’s report, Walther Bohnke, eldest son of Lilli and Emil, began to disseminate the complaint of theft in various specialized media, such as the magazine The Strad, where he published in 1958 an ad accompanied by a photograph. Not only did he gathered numerous testimonies until his death in 2000, but also requested help from Interpol and managed to join the Database of the German Foundation for lost art, which document confiscated cultural goods as a result of Nazi persecution.

At present, the three children of the Mendelssohn-Bohnke have already died, but David F. Rosenthal, the main percussionist of the San Francisco Ballet Orchestra, acts as a family representative, as he is grandson of Lilli von Mendelssohn-Bohnke and great-grandson of Franz von Mendelssohn. He also responded to El País by email. “I grew up listening to this violin and its robbery, and most family members thought it had been destroyed after looting, although my uncle Walther Bohnke never stopped looking for him,” he says in the Shapreau report. He concludes with the main reason to recover it: “It was always known as my grandmother Lilli’s violin and is a fundamental piece of the Mendelsso-Bohnke family heritage. It connects us with our past in a very deep and significant way.”