The Internet Society Panama Chapter had a plan. They would build the country’s first community network and bring the Internet to one of the country’s many Indigenous communities that were still offline.

“Indigenous communities are the most forgotten. Some live 20 to 30 minutes from the city and yet don’t have Internet access,” said Julio Lezcano, director of the Panama Chapter’s Community Networks Committee.

Over the years, Indigenous communities across Panama heard a lot of empty promises from politicians pledging bare minimum connectivity. They also heard from NGOs offering services they didn’t need, in exchange for a photo opportunity. The Panama Chapter promised something different: high-speed Internet, skills training, and community control of the network.

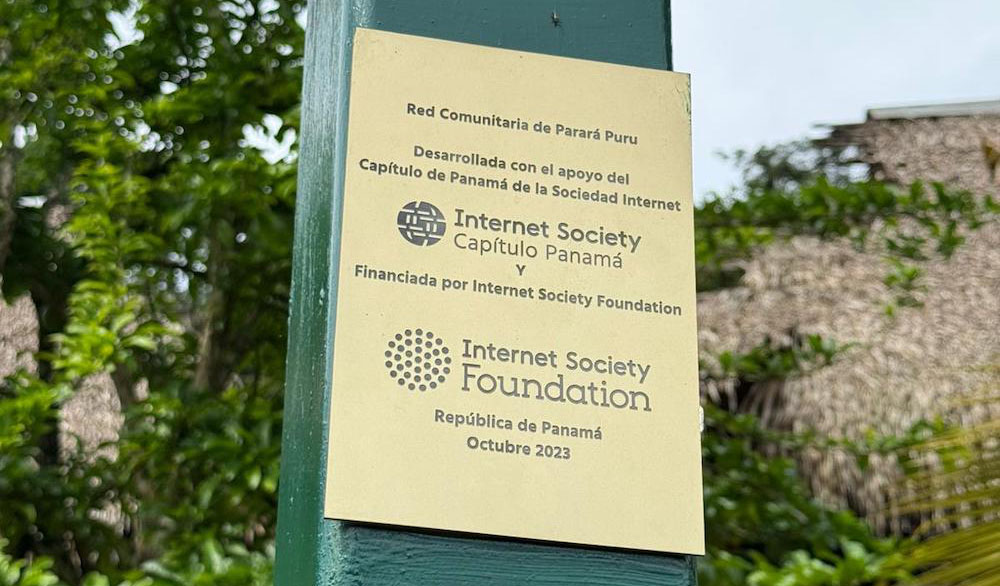

The chapter chose the Emberá village of Parará Puru as the location for the project for the simple reason that it was closest to Panama City, where most chapter members live. Proximity is just one of many foundational considerations when relying on a volunteer network with full-time jobs and families.

Another early consideration is funding. “Commercial Internet service providers always look for areas where they can profit more. But in this area, they don’t see a return on their investments,” explained Julio. Chapter members Rachel Vazquez and Pablo Ruidiaz were able to secure funding for the project through a Beyond the Net (BtN) grant from the Internet Society Foundation. BtN grants are given exclusively to Internet Society chapters to support innovative connectivity projects.

Although no one expected the process to be easy, nothing prepared them for the number of hurdles—bureaucratic, technical, geographic—they would have to jump over to meet their goal.

First off: close doesn’t mean easy-to-reach. Parará Puru sits on federally protected land, along the Chagres River. The community’s main source of income is tourism, which requires communication with vendors and visitors. But in order to make a phone call or send an email, they had to take a boat to the mainland then travel by bus to reach a signal. Which is a tough way to run a business.

“When the river is low, you have to get out at some points to push the boat past the shingles. Conversely, when the river is flowing too strongly, you spend an hour fighting the current to go upstream. So the boat ride alone can vary from 15 minutes to an hour,” said Russell Bean, another chapter member who helped build the community network and has since joined the Internet Society as a full time Internet exchange point development expert. Throw in Panama City’s famously congested commuter traffic, and it can take anything from 40 minutes to over two hours from Panama City to Parará Puru.

In Panama, any network that charges fees for service is considered an Internet provider. And in order to be an Internet provider, you have to have a license to operate. It’s one thing for a telecommunications company to get a license, but for a village with under 100 inhabitants, it’s just about impossible. Thankfully, the government made an exception for Parará Puru, but the rule is still in the books.

Originally, when the Panama Chapter surveyed the topography of the village, the best network design option was … complicated: erect a long-range antenna on top of a hill and connect to the only man-made structure in visible range, a cement factory. Next, lay down fiber to connect to the neighboring village. “The one available path for fiber was a mud track, not even a real path. We think it would have been possible,” said Russell.

In the end, they didn’t need to test their hypothesis about the mud path, because a new low earth orbit satellite service became available and changed everything. “It went from being a very difficult, technical project with huge costs and a 20-meter tower to a four-meter pole and some solar panels.” If they were starting from scratch, Russell would skip the complicated surveying altogether.

“One of the first (benefits identified by the leaders) is that with the Internet access, they could communicate instantaneously with the tourism agencies that bring visitors to the village, where they live,” said Julio. “It allowed them direct communication with the hotel and the ability to monitor visits.”

The Parará Puru community network set the bar for what community connectivity in Panama can and should look like. “It’s been so successful some politicians are now taking credit for it,” said Russell. Now the Internet Society Panama Chapter and the Emberá people of Parará Puru are advocating for more connectivity for other Emberá villages and Indigenous communities across Panama.

Russell’s advice for anyone who wants to build a community network? “Don’t give up.” In all, it took four years of diplomacy, regulatory and legal wrangling, surveying, engineering, logistics, and collaboration to make the community network a reality. “There were so many moments when we could have given up.”