Photo editor Carl Robinson had been silent for 50 years, but he had not forgotten what happened on June 8, 1972 in the office of the AP agency’s correspondent in Saigon. When he finally began to speak many decades later, after a meeting with old colleagues who were like him in the Vietnam War, his words reached Gary Knight. And it was this veteran war photographer and founding member of the VII agency who decided, together with his wife Fiona Turner, to dedicate themselves to history and continue pulling the thread. The fruit of his determination to “discover the truth” is The Stringer, as Knight himself explains in the documentary, presented this Saturday at the Sundance festival.

The story that Robinson kept silent for half a century, and that Knight decided to investigate in depth, has to do with the authorship of one of the most iconic images of photojournalism in the 20th century, a shot that fully impacted American public opinion and that , according to the official story, was taken by Nick Ut, a 21-year-old Vietnamese photographer, a staff member at the American agency AP. In the center of the image, a nine-year-old girl runs naked and burned along the road, sobbing and with her arms crossed. There are other terrified children running nearby, three soldiers behind them and as a backdrop a thick cloud of smoke, traces of the napalm bombs that fell in a failed operation on the Vietnamese town of Trang Bang on June 8, 1972.

The then president of the United States Richard Nixon even asked one of his advisors if that photo was not a montage due to the perfect summary of the horror of the war it reflected and its overwhelming echo, as recorded in recordings from that moment. The napalm girl in that photo, titled The terror of warmarked a turning point. The last American troops left Vietnam a few months later. In January 1973 peace was signed. The Stringer Nothing about all this changes, and yet the hour and a half film aims to shake up and question some of the ethical foundations of American photojournalism.

Was the photo attributed to Nick Ut when the author was another Vietnamese photographer who was in that place and who has remained in the shadows since then? Was it the famous Horst Faas, head of the bureau of AP in Saigon, who gave the order not only to go ahead with a photo of a naked girl that contradicted the agency’s rules, but also to have Ut’s signature appear even though the film from which the image came was, according to Robinson, noted with another reference? These are the questions that Gary Knight tries to clarify, whose investigations lead him to find the stringer of the title, supposed real author of the photo: Nguyen Thanh Nghe. This army photographer had trained as a filmmaker and that morning he drove the CBS crew car to the fatally bombed town of Trang Bang. In the documentary, Nghe explains that he took his film to AP and they gave him a copy of the photo of the napalm girl and $20. An NBC sound manager, Tran Van Than, says that he was the one who accompanied AP and managed that. Nghe’s wife destroyed the copy of the photo. And although he did not win any Pulitzer like Nick Ut in 1973, nor enjoy his fame, he also left Vietnam in the seventies and has lived in California ever since.

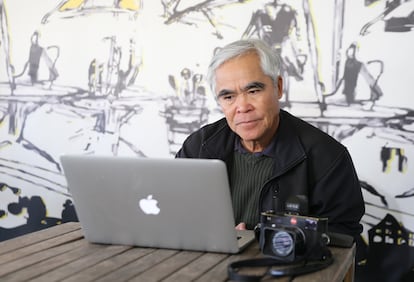

No one disputes that Ut was there, but he took the photos from further away, Nghe maintains, and his claim is confirmed by image analysis experts from the Index agency in the film, who affirm that it is “highly unlikely” that he took that photo. “When I saw that analysis it seemed convincing to me and I understood that I had to make the connection between Gary Knight and AP,” explains Santi Lyon, a photographer who worked for 25 years at the American news agency, where he became vice president and head of the entire news area. photograph. “This is a story of justice, because the freelance “He has no voice,” he explains into the phone.

The efforts of Lyon, who appears briefly in The Stringer, They came together in a meeting that led to a dead end: the agency would not sign any confidentiality agreement, as Knight and his team demanded. AP, however, prepared a report as a preventive response to the documentary, after undertaking an investigation for six months. “In the absence of new and convincing evidence to the contrary, AP has no reason to believe that anyone other than Ut took the photo,” said the report, prepared from the testimony of seven people and scrutiny of the negatives.

Two of the fundamental sources in this story, the man who revealed the photos, Yiuchi Jack Ishizaki and the head of photography bureau, Horst Faas, they are already dead. It is not clear what or who gained anything by attributing the photo to the young Vietnamese man Ut, who had been employed by AP for six years, and whose brother had died working for that same agency seven years earlier. Robinson, who now exposes the fraud, left AP in 1978 and, although he has written a several hundred page book on Vietnam, he did not talk about it. AP rescues a photo in which he is seen toasting with champagne with the rest of the agency’s team in 1973 after it was announced that Ut had won the Pulitzer for the same photo, whose authorship he now claims was someone else.

Be that as it may, the doubts raised The Stringer They go beyond the photo, and despite not having the testimony of the photographed girl, neither of Ut, nor of AP, the many interviews that the documentary brings together raise questions about who really took the young woman to the hospital, the chronological order of the images and where exactly Ut was on that road to take that photo. It also calls into question the use that the AP agency and many other news organizations have made of the work of stringers y freelancers which, as Knight points out, “they only have his signature.” The film is dedicated to “Vietnamese photographers of the American war in Vietnam and to the stringers brave men of today’s wars”, and at one point states that Ut himself is a “victim” in this story.

Beyond the fact that it can be conclusively proven what The Stringer defend and force the rectification of AP, or of the complaint that Nick Ut through his lawyer has announced that he would file against the documentary team, there is no shortage of those who remember that there are more cases in which authorship has been questioned. An example: Robert Capa and his collaboration with Gerda Taro, so close that they signed the photos of both as Capa, and about whose image of the fallen soldier there are still suspicions of a montage. “All of this falls under the academic review,” says Thomas Dworzac, former director of the Magnum agency. “Perhaps the question that should be asked about the photo of this girl in Vietnam is whether something like this would be published today and also what impact images of war have today. I am afraid that much less than what they had at that time when their echo was even greater than that of television.”

Others, such as Fred Ritchin, dean of the International Center for Photography, also wonder about the opportunity of research by The Stringer: “This is a strange moment in the United States to open this conversation and present the documentary, in the same week that Trump’s inauguration is being celebrated. That iconic photo reminds us that none has been taken with such an impact in the wars in Gaza or Ukraine and, however, that form of resistance to the power that photography represented is still necessary.”