The history of human fascination, and greed, for gold is lost in the night of time, told over the centuries with mythological stories, such as King Midas; Legends like El Dorado, a city that Spanish conquerors sought; In films that taught gold fever in the distant west of the United States, or in the photographs of Sebastião Salgado that portrayed the anthill of prospective In the Amazon, in search of a cup of the precious metal. However, gold is also a material to capture artistic beauty in filigree, perforated plots and rich decorative motifs, as the collection of more than 300 objects shows that can be seen for the first time in Spain, in the exhibition The gold of the Akan. Royal Treasures of Western Africa, in the Barrié Foundation (A Coruña), until July 13 and with free admission.

The Akan are a set of villages that inhabit partly in the coast of ivory and Ghana, virtuous in the elaboration of some pieces that not only attract because of their brightness, but also contain a whole symbolic code, either to represent power, religion or respect for their deceased, and that were made to exhibit their kings and senior leaders. The objects, however, come from the old Europe, from the Liaunig Private Museum, in Neuhaus (Austria), where they had only left one occasion to expose themselves in Iphofen (Germany). Interestingly, this collection of African art is the counterpoint to that of contemporary art that houses the Austrian museum.

At the beginning of the tour, a salacot, the typical hat of the explorers, in wood and gold, dated 1935. Most of the objects are from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, although there are some oldest. A lower jaw can be seen next to the Salacot. “The Akan took them from the enemy because it was a way of seizing their voice and history,” explained the gallery owner and African art expert Jean David in the presentation to the press this Friday. David was accompanied in the guided tour by the director of the Liaunig Museum, Peter Liaunig, and the director of the Barié Foundation, Carmen Arias (institution that invited this journalist).

It was Jean David’s father, René (1928-2015), who lived in Ghana-a part of this country was known as the Costa del Oro-and gathered a large collection of tribal art over forty years, in which he also traveled through Mali, Cameroon, Congo and Ivory Coast. David’s narrow contact with Ghana’s royal family led him to give them part of his group, the organizers tell. While the collector Herbert Liaunig (1945-2023), Austrian, was buying pieces in the art gallery of David in Zurich until the son of the gallery owners, Jean, when he was already in charge of the business, offered him the complete collection: about 400 objects.

At a time like the current one, in which museums from all over the world rethink the colonial origin of some of his works, David has defended that his father “since the sixties traveled to Ghana and fell in love with his culture, bought objects, which were sometimes almost thrown and did not cost much. Everything was legal and was the first European who opened an intercultural museum in Africa. ” “In addition,” he says, “we must bear in mind that they used to sell these jewels to gather money with which to send their children to study abroad. It was not a sacred material for them. ”

Perhaps some of those sellers held in their heads the spectacular crowns of gathered regents, such as the one decorated with small knives and a war horn, a distinctive power. Or the one that shows two erect lions on their hind legs. There are also wood and gold control canes, intended for the king’s spokesmen, in whose handles we can see antelopes, turtles or snakes or an elephant that avoids a trap. “It represents that the king is above all and that he is saved from falling into that trap,” according to Liaunig.

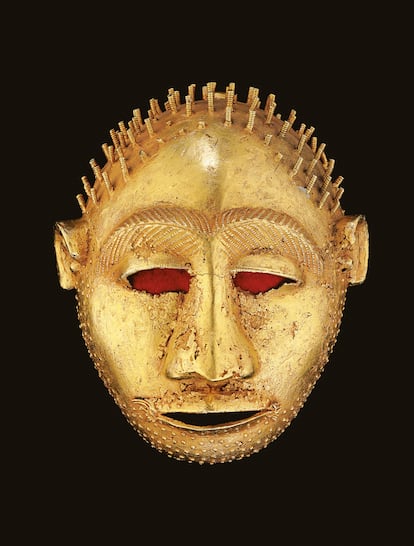

Next, emblems of swords, with which the warriors decorated them, like that of an almost human face lion and huge fangs, made in 1915. “The warriors gave these swords to their king as a sign of fidelity, which later returned them,” David explained. The Gold of the Akan – who a good title for a Tintin album – is also in arms like a hunting rifle and in the so -called “executioner knives”, with horn handles.

Courtesy of the Liaunig Museum and the Barrie Foundation

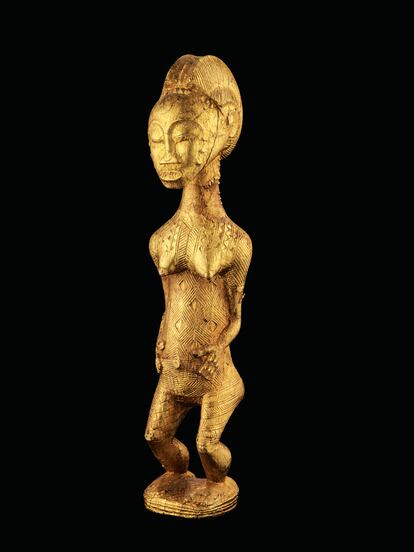

More delicate are the small carved female figures, with dense and flat surfaces, and the spectacular rollers with gear, snakes or lions. An Akan King could take up to 10 rings, although due to the size of these there were only a couple or three in their hands.

It is not difficult to be speechless to see how the “pectorals of mourning” shine, round pieces that the relatives of the deceased were hung by the neck. The Akan not only joins this wonderful gold work, but also a political organization in the form of a monarchy (only men reign, but the successor is only chosen by the queen mother), a common language, the twi, and its religious beliefs.

Closest to European culture are the bracelets, in solid gold, which, according to the poster, the head of the tribe was placed on the left arm, while in other cases, adorned with amulets, they were adjusted, between three and five, in the upper part of the right arm.

In a section the variety of utensils used to weigh the gold powder, which did not prevent them to also have an artistic treatment. Ground gold was used as a currency between the early fifteenth and 20th century and a video tells the complex handmade processes with this ductile and malleable metal. Liaunig emphasizes that among the Akan, the goldsmiths “are always men, it is a trade that passes from parents to children and that is considered very complicated because, according to their beliefs, they work with a piece of the sun,” and David adds that the status they have in their society “is very high.”

The end of the tour is chaired by two pieces. A throne of wood and gold, which Liaunig points out that kings used it “because it has the backing slightly inclined back; If it had been for a magistrate I would be straight. ” And some real sandals in leather and gold. A good ruler must have the feet on the ground, but in this case they were manufactured for the king “because he could not touch the ground, he could not go barefoot.” And since not everything was going to be so majestic, there is room for more prosaic utensils, such as a small richly decorated album whose center is a rod. David stops before the showcase and says: “It was to clean her ears.”