The year was 1989. Douglas Coupland, then just a 28-year-old Canadian advertising copywriter hired by a publisher to write an essay about the boomerssettled in the Mojave Desert and began to shape a novel with a fragmented layout—pieces of cloudy sky, here and there, that is, images like prehistoric banners— that I had never planned to write and that not only gave name but above all content, prefiguration, to a generation. The stormy and sad generation romantic love

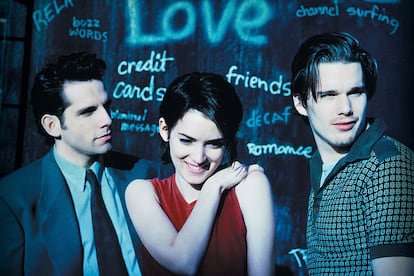

The clearest example of what Coupland labeled in Generation It is Ben Stiller’s cinematic classic The harsh realitywhich starred Ethan Hawke and Winona Ryder, two icons of the time. “I didn’t even pretend to be a writer. “I ended up being one by accident,” said Coupland, who since the publication of that text in 1991 has delivered a work – novels, collections of stories and essays – every two, three or four years, including the award-winning and extremely visionary novel Microserfs (1995). Until 2013, he began a hiatus during which he dedicated himself to art—he made a pixelated whale and a sculpture that visitors had to modify with their chewed gum, among other things—which closed in 2021 with the publication in English of Binge (Binge), a collection of 60 short stories edited now in Spanish by Alianza with translation by Juan Gabriel López Guix.

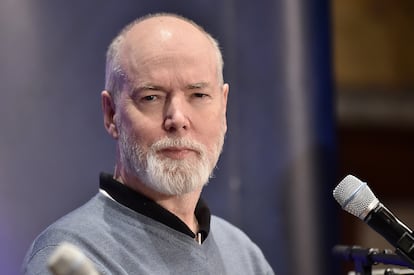

The same label is also preparing the reissue of Generation y Microserfsat a time of renewed interest in the work of the Canadian author. Perhaps because of his ability to dissect the anxieties and challenges of the hyperconnected society. Coupland’s works of fiction, today a 62-year-old guy far from the spotlight to the point that communicating with him is an impossible mission — he has avoided the request for an interview with EL PAÍS for weeks and has not answered questions of any kind for years -, detail a society of unique individuals domesticated, destroyed and collectivized by capitalism, the system that, in search of clients, turns everything it touches into a product – relationships, people, everything that can be felt – and , At the same time, it alienates and distances its inhabitants from reality, subjecting them to an infantilization that prevents them from maturing. All they are is all they desire, and they desire without consequences, like children or, better yet, like adolescents. The only way out of this overdose of oneself is a upgrade of product, to be another, to be reborn in your own body.

It happens to one of the characters in the microstories of Binge. The protagonist of ComRom She doesn’t know why she’s alive. “I contribute zero to society,” it is said. “It seems paradoxical to me that, despite my general uselessness, if you killed me, you would still have to go to prison for murder.” “I don’t want to be dead, but I don’t want to be me. I’ve been doing it for 52 years and it hasn’t gotten me anywhere,” he repeats. I am of no use among so much product, so why exist?

More than a critique of the system, Coupland’s fiction performs an autopsy, since in his stories capitalism seems to operate from a beyond in which the human being is a collection of neuroses barely held together by an idea of the self invaded by desire. of being an infinite number of others. Their characters are pieces of a gear that have forgotten that they were once more than just pieces of that gear. What defines them are their weaknesses, what makes them unique, in the worst of ways. The future, for them, is a pure mirage, a hamster wheel that doesn’t plan to stop. All of this developed with an endearingly wild sense of humor, a peculiar pop absurdity that has greatly influenced the fiction of this 21st century, from Alexandra Kleeman to Sheila Heti, through Paul Murray and the Pulitzer Prize winner Joshua Cohen.

What mediates between that Microserfsthe first glimpse, precarious and alienating, of life on the other side, that is, inside the computer screen – the protagonists are geeky office workers, an approximation to a prehistoric Silicon Valley devoid of all glamor – and this Binge It is a sophistication of the way in which Coupland approaches the loss of innocence and any type of hope from the most hopeful of worlds: the one that seeks to sell perfection and, at the same time, a standardization that in the age of Instagram has made the human being its own product.

Perhaps the Canadian writer and artist who was born in West Germany has done nothing else in all this time than write what he could not write in the Mojave Desert. A long treatise—in fiction—on the boomersor better, its consequences. After all, his characters are deluded and immature adults, terribly spoiled big children, condemned to live in a world of inaccessible desires. A world divided into clients and employees and in which, as the title of one of his classics says, All families are psychotic (2001), because they cannot not be.

“I am curious about the moment when personality becomes a pathology,” he wrote not too long ago, convinced that the era of social media is accelerating the erasure of what makes us unique and promoting the product—the self. identical, what he calls “autophobia”, the fear of being different. “Let’s be honest, being unique is not easy. It’s very hard. It is better to be like the rest, and feel alone and at the same time part of something. Today’s human being is not prepared to think for himself,” he ruled in that same essay, published on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the arrival of Generation to bookstores, in that distant 1991 in which the end of the century was a threat and, at the same time, an opportunity that the world was clearly going to miss. Hence all that bizarrely nostalgic anguish that remains intact today because everything was lost even then.