The life of the Portuguese writer Eça de Queiroz began in hiding in Póvoa do Varzim in 1845, born of an “unknown mother”, and, somehow, he ended this Wednesday in the National Pantheon, in Lisbon, surrounded by other greats of history from Portugal. Although his biological existence ended in 1900, his remains have traveled through various locations until reaching the church of Santa Engracia, where the main authorities of the State have paid him a tribute that can be considered a final point. The author of The Mayans He arrived where he had to go, “the place of the immortals”, in the words of the President of the Republic, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa.

Eça de Queiroz will now rest alongside other Portuguese who were protagonists in politics or culture, among others, a fadista (Amália Rodrigues), a footballer (Eusebio) and a general murdered for fighting the dictatorship (Humberto Delgado). A company of undesirable glories, for some members of the writer’s family who opposed the transfer and who failed in their attempt to veto the move in court, as defended by the majority of the 22 great-grandchildren. In June 2024, the court settled the issue and endorsed the proposal of the Eça de Queiroz Foundation, which resumed the organization of a ceremony that had had to be postponed in 2023.

The head of State, Prime Minister Luís Montenegro and the highest authorities of the country participated in the institutional session. During a long ceremony, actors and academics read passages from his most famous works such as The crime of Father Amaro o As Farpaswhile an honor guard escorted the coffin. In the midst of the pomp, the writer and president of the Foundation, Afonso Reis Cabral, recalled that Eça de Queiroz “arrives at the Pantheon carried on the shoulders of the people who have read him so much, read him so much, or will read him so much.” “It continues to be read in the 21st century, translated, studied by academics, but it has also been caricatured, taken to the theater, turned into a statue and even a pop figure; It is the proof of posterity,” he highlighted.

The novelist’s remains stumbled a few times. For nine decades it was in the pantheon of his in-laws, the counts of Resende, in the Alto de São João cemetery in Lisbon, but deterioration led the family to move it in 1989 to a tomb in Santa Cruz do Douro, in the municipality of Baião, where a country house had been rehabilitated and became the headquarters of the Eça de Queiroz Foundation. “This fair tribute could have already occurred years ago, taking into account that it was in a provisional grave for almost a hundred years,” declared the former Minister of Culture and Queirosian specialist, Isabel Pires de Lima, to the RTP network.

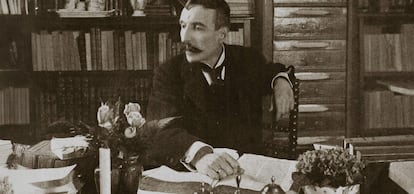

Eça de Queiroz died at the age of 54 in Paris, where he was consul. Despite his work as a diplomat, he had time to create one of the best legacies of 19th century Portuguese literature. “The idea of the country that we still have is his,” highlighted his great-grandson Afonso Reis Cabral. “He is the writer who reveals our vices and who best denounces our collective defects,” stressed the president of the Assembly of the Republic, José Pedro Aguiar-Branco.

Satire was one of his traits, which he cultivated both in journalistic writings and in gatherings such as the one formed by the group Vencidos por la Vida, where some of the most brilliant intellectuals of that century were integrated, such as the historian Joaquim Pedro Oliveira Martins or the writer José Duarte Ramalho Ortigão, with whom he wrote The mystery of the Sintra highwaypublished as anonymous letters in the News Diary during the summer of 1870.

Eça de Queiroz himself was a character full of contradictions and extravagances. He dressed like a dandy and lived beyond his means while advising his wife, Emília de Castro, to be stingy. “Times are gloomy, greed is a duty, an imperious necessity,” he urged in a letter in 1898. Meanwhile, the writer continued to choose expensive mansions for his summer vacation and stayed in luxury hotels every time he traveled. His economic asphyxiation, despite his official salary and his literary income, was permanent.

The great mystery of his life was, however, his relationship with his parents, who married when the writer was four years old. At the time of her birth, her mother, Carolina Augusta Pereira, settled in the house of a relative in Póvoa do Varzim to avoid the scandal of giving birth unmarried in her town. Eça de Queiroz was registered with the surname of his father, Judge José Maria Teixeira de Queiroz, but as the son of an “unknown mother.” Educated by mothers, grandparents, uncles and boarding schools, he barely lived with his parents and siblings. A biographical aspect that marked his literary universe. Specialists in her work highlight the absence of maternal figures in her novels. “And if there are,” Isabel Pires de Lima pointed out to the magazine Saturday“they are problematic.” Of the many letters exchanged by Eça de Queiroz with friends and relatives, none were addressed to her mother or sent by her.