“This afternoon I have gone with the children to visit the burial of Platero, which is in the Pineapple Garden, at the foot of the Round and Paternal Pine”This was how Juan Ramón Jiménez referred to the tree almost 20 meters high and 3.80 perimeter, where the hairy, small and soft donkey was buried, with cotton belly, the protagonist of his most universal work. That pine, of more than two centuries of life, has just been starting from rennet by the tornadoes that last week razed part of the coast of Huelva. Recover it to return not only the sap to its hundred branches, but to prevent a symbol of the Juanramonian narrative, which has also become intangible heritage of the municipality of Moguer, where it sank its roots.

“We are talking about irreparable damage, but it is a good that can rebound,” explains the mayor of Moguer, Gustavo Cuéllar. The pine was erected on a sand of sand and its roots were at a very superficial height. The large amount of water accumulated by the Borrascas train that lasted Andalusia last week caused the floor on which they were supported and that they could not endure the tornadoes that accompanied the storm. “I had a lot of weight and the strength of the winds has lying it,” corroborates Antonio Ramírez Almansa, director of the Zenobia Camprubí-Juan Ramón Jiménez Foundation.

The technicians and experts of the Ministry of Environment of the Junta de Andalucía who have analyzed the situation of the tree this Monday have proposed “cover the roots with a mortar of humus and natural substrate of the environment, clean up the cup cleaning and cutting many of the branches that are open and dry,” according to the mayor. “We are not going to know if it recovers until a safe time passes, but now the essential thing is to close the open wound and avoid that, now that it has stopped raining, the roots dry,” he abounds.

“That pine was gorgeous,” laments Carmen Hernández-Pinzón, granddaughter’s niece and responsible for the legacy of the Nobel Prize for literature and that has been claiming more attention to the preservation of that tree, cataloged as a singular species. “The last rains have finished finishing it, but it was seen coming that it was going to fall,” he says. Hernández-Pinzón refers to how at the beginning of the century the foundation denounced the abandonment of the area and that at his feet accumulated the garbage left by a group of occupies. “Two months ago there were some technicians and elaborated a file in which it was requested to acted with immediacy because the Cup weighed a lot, they had dry branches …”, he details and emphasizes that he has also suffered the evil of the processionary. “There has been carefree,” he says.

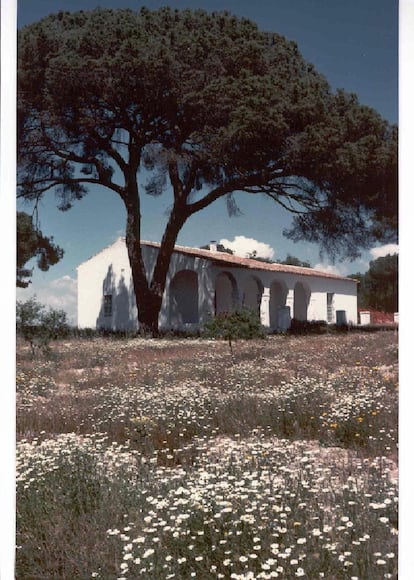

Ramírez Almansa, however, affects the age of the tree and how the strength of the hurricane winds last week has also started a fifty centenary pines in the area. Juan Ramón’s pine is located on the side of the house of Fuentepiña, on the Santa Cruz de Vista Alegre estate, privately owned. “The poet always wore a stone of fountain in his pocket. There he wrote endless books, including Silversmith And many more, ”says Hernández-Pinzón. That was Juan Ramón Jiménez’s summer house between 1906 and 1910 and the Junta de Andalucía could never declare it well of cultural interest, although he tried twice.“ There were errors in the processing of the file that was appealed by the owner family, ”explains the mayor of Moguer, who indicates that he is not putting any obstacle in the operation to deal with relive the tree.

“Juan Ramón spoke of eternal pine. “In the celest and warm light / in the slow morning, / for these pines I will go / to an eternal pine that awaitsthey are the first verses of the poem Pinar of Eternityas you remember. “This pine has been universalized through the poet’s work. The burial of Silversmith Under its roots it is an example of its connection with nature, with the concept of eternity and transcendence. The poet buries it there with the idea that the essence, the goodness of Platero will last beyond death, ”adds Ramírez Almansa.

That pine also symbolizes the identity and belonging of the Nobel with the landscape of his homeland, which he had physically in his stone -shaped pocket. It is the tree that Juan Ramón met in his youth and that his countrymen have also made his. Many of the neighbors walked to Fuentepiña to photograph themselves and the schools led their students to read their poems or plateria. “We feel very sad for the situation of the tree because many felt the Juanramonian spaces as some public ownership,” index the mayor of Moguer.

The tree really seems eternal. In recent years he survived intact two fires. “He has been surrounded by fire, he has not been able to drought with him, he has been part of the history of natural and unnatural events caused by man, and yet it seems that water is what he could with him,” the director of the Foundation laments. But both he and the mayor refuse to talk about pine in the past. “It’s alive,” emphasizes Ramírez Almase. “And that gives us hope,” abounds the councilor.

“In the temperate light and one / I will arrive with a full soul, / the pinewood will rumorear / firm in the first sand.” This concludes Pinar of Eternity And firm in that sand that has not been able to sustain it before the envy of the winds of the last days is how the authorities hope to return to the eternal pine that Juan Ramón dreamed and that also the dream of butterflies and lilies of Silversmith.