That my brother Carlos gave me for Christmas the lead figurine of a German submarine captain from the Second World War (Günther Prien, the one who put U-47 in Scapa Flow and sank the battleship HMS Royal Oak) has returned me to the turbulent time of the gray wolves and their constrained world of steel coffins. The curious circumstance occurs that I had bought the same figurine to give him as a gift – at the final sale of the much-missed Stock bookstore on Comtal Street in Barcelona, where over the years I have found things as good as the model. of the japanese battleship Yamato which I sent to the writer Jan Morris—so that now I have two identical German submersible captains (I finally gave my brother a coat), which refers, of course, to other brothers, the Ites, a singular case in the submarine force of the Third Reich (and in any other). The Ites, Otto and Rudolf, were identical twins and both U-Boat captains (Unterseeboot, submarine), so when Admiral Doenitz saw them together he must have thought he had gone too far with the schnaps. Otto (1918-1982) was a notable officer who, after training in torpedo boats, commanded two submarines, sank 15 enemy ships and earned the Knight’s Cross. He survived the sinking of his second submersible, U-94, in 1942, and was taken prisoner. After the war he became a dentist (probably credited to the fear he had caused at sea) before joining the new German navy and ending up as Konteradmiral. Less famous and fortunate, Rudolf (1918-1944), did not sink anything and sank with his first command, the U-709, on its first patrol.

My two little figures, as alike as the U-Boat twins, have taken me, therefore, to the depths and hazards of submarine warfare, a subject that interests me both historically and morbidly given my irreducible claustrophobia and whose attraction even led me One day, surprising myself, I embarked on a combat submarine, an adventure that confirmed my opinion that it is better to read about submarines than to get into them. By chance, on Twelfth Night, an old book of World War II stories from 1960 also fell into my hands, which contained Rear Admiral Daniel V. Gallery’s account of one of the most spectacular episodes of the war: the capture in 1944 of a German submarine by a US naval group led by the aircraft carrier USS Guadalcanal and under whose command was Gallery himself. The guy was a kind of cowboy obsessed with capturing a Nazi submersible on the high seas and being the first since 1815 to shout “board!” from a ship of his country’s navy.

The fact is that he did it: he caught U-505 off Mauritania and took it home. The way he tells it is incredible and makes you think about the hands in which the US has often placed its fleet. After forcing the submarine to surface with depth charges from its destroyer escort, Gallery relates, “I said to myself, Now it’s yours!, and taking hold of the microphone I launched the ancient command voice never before heard through the loudspeakers of a modern warship: “Boarding!” And he adds: “Our plan worked out wonderfully.” While the Germans abandoned the ship in a pandemonium of terror, gunshots and urgency, an assault party arrived at U-505 and, advancing in the opposite direction to the fleeing crew members, jumped into the water and entered the submarine. If there is anything worse than getting into a submarine (you have to have gone down the turret hatch to see how narrow it is and what a narrow world it leads you to) it is doing so in an enemy one in the middle of the ocean, in the middle of combat, with its occupants tense. and doing everything possible to sink it to prevent its capture. The handful of brave men who took U-505 (one won the Congressional Medal of Honor) didn’t know if the sub would stay afloat, if the demolition charges the crew used to activate would explode, or if there would be some fanatical Nazis down there waiting for them. Luger in hand.

They finally managed to secure the U-Boat and lay a cable for the aircraft carrier to tow it. And Gallery achieved his submarine. When the “ugly snout” of the submersible was left with the four loaded torpedo tubes almost touching the stern of the Guadalcanalthe rear admiral – he himself relates – prayed that none of his prying crew members pressed the launch button. Gallery found an opportunity to board the submarine himself—the turret of which was playfully repainted in the purest tradition of Operation Pacific by Blake Edwards—with the excuse that he was an expert in booby traps. He was ecstatic, and in his story he highlights the importance of capture when taking signal codes. In reality, as the scholar Mark Lardas explains in the most precise and serene The capture of U-505 (Osprey, 2022,) Allied commanders were amused by Gallery’s obsession, but they never thought he would make it a reality. In fact, the capture of the submarine on the eve of the Normandy landings put them in a hurry and on their nerves, since they had long ago decoded the German secret codes and had obtained Enigma cipher machines from other submarines. The news of the capture of a German submersible, if it reached the ears of the enemy, would have caused the Nazis to change their system, so the aircraft carrier and its prize were sent far away, to Bermuda, to hide U-505 there. under the not very imaginative name of Nemo.

I am reluctant not to add that U-505 (on display in Chicago) was an unfortunate submarine: its previous captain, Peter Zschech, had committed suicide on board during a mission (I travel on a submarine and I am told that he committed suicide the captain and I throw myself through the torpedo tubes). He was replaced on the final voyage of U-505 by Harald Lange, the oldest U-Boat commander of the war and who never sank anything. Lange was saved that unfortunate day, but, in addition to his submarine, he lost a leg.

The most amazing thing about the capture of the Nazi submersible, given how difficult and risky the matter was, is that it was by no means the only one. The Allies—see Enigma U-Boatsby Jak P. Mallmann Showell (Ian Allan publishing, 2009, revised edition)—they tried and succeeded several times. Among the notable cases, Lemp’s U-110 (the only one I know of that fired its deck gun without removing the plug), trapped by British destroyers within sight of Greenland in 1941 and which provided many secrets, including its Enigma machine ( the story inspired the questioned and sometimes crazy but very exciting film U-571, who exchanged British for Americans); the U-570 of the unfortunate Rahmlow, branded as a coward, who surrendered to a plane! and that the submersible presented a Dantesque appearance as its lavatory had burst (one only for 50 crew members with an unhealthy diet and loose bowels due to the depth charges); Heidtmann’s U-559, which sank —voilà the courage— with two of the three members of the British boarding party inside (the survivor later died, what must be seen, on the ground in a fire); the U-852 stranded in Somalia and captured by a camel-mounted troop, or the U-175, caught in the middle of a bloodbath with its captain, Bruns, mutilated in the turret beyond recognition by destroyer fire that surrounded it on the surface and sprayed the submersible with a furious hail of steel. The U-250, whose captain was Werner-Karl Schmidt, who had been a bomber pilot in the Battle of Britain and on the Russian front (an extraordinary case of versatility), was the only U-Boat captured by the Soviets, after they sank it. a torpedo boat and be refloated. The scene they found when they opened it was tremendous: 46 drowned crew members still floating in a layer of water with a lot of eels snaking among the corpses.

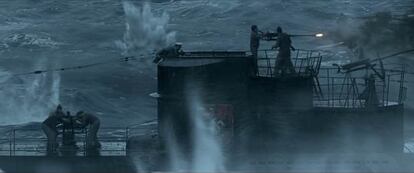

To get into the mood during these days of submarines, I have taken the opportunity to watch on Apple TV + Greyhoundthe Tom Hanks film about convoys and submarine herds that I had pending. I liked it a lot, although it has flaws that you don’t need to be a student of the Battle of the Atlantic to notice. The main one is that not even the most brainless Nazi submarine captain would dedicate himself to launching radio messages making bullying to the destroyers. The psychological harassment tactic of the fictional Gray Wolf—voiced by that specialist in Nazi roles, Thomas Kretschmann (Fegelein, Eichmann, the music-loving officer of The pianistthe lieutenant of Stalingrad, the German captain U-571)—, and which includes launching a wolfish howl more typical of a disc-jockey from the sixties, it’s just bullshit. The film confuses Doenitz’s gray wolves, who were Nazis but were professionals, with the Rose of Tokyo or Lord Haw Haw.

Greyhound is based on the novel The Good Shepherd (1955) by our admired CS Forester, creator of the unforgettable Captain Hornblower. Hanks embodies Captain Krause very well, with his self-denial, his doubts and his religious devotion. A curious reverse of the expansive Rear Admiral Gallery and his determination to acquire a submarine. We’d probably have a better time drinking at Gallery. TO Greyhound, In any case, with its absolute demonization and dehumanization of the enemy, whom we do not see at any time (only the submersibles), it lacks that point of moral complexity of cruel sea (Nicholas Monsarrat’s great novel and subsequent film), in which the captain and sailors of the corvette Compass Rose They are disturbingly confronted with the crew members of the hated submarine they have sunk and those they have rescued and taken prisoner. Nazis but seafarers, seafarers but Nazis.