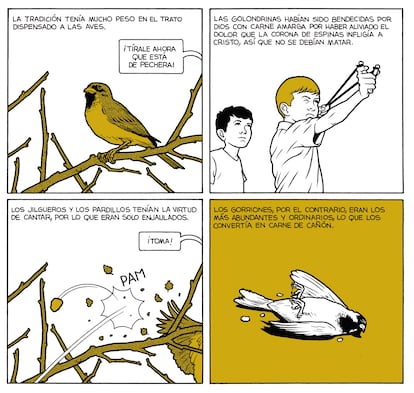

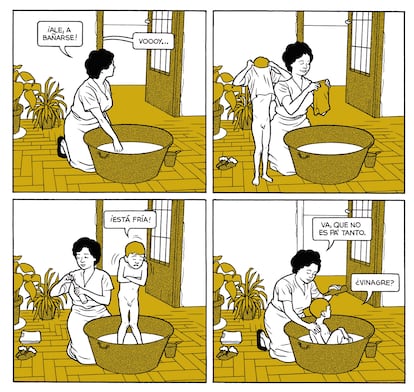

This is the story of a double separation: that of a time that was not his and a place he never inhabited. This is what César Sebastián narrates and draws in Ronsonis the story of a Spain that was and died out: a country of watering troughs and sheds, of town criers and leather workers, of dirt streets with donkeys trotting, of powdered milk and tin tubs to bathe children between stables and carts. A country of wakes with rosaries at home, slingshots to shoot down sparrows, cats treated with kicks, the caravans of the gypsy circus, pesos with a bushel and a barchilla, the smell of grain on the threshing floor and the ineffable taste of the lost afternoons of childhood.

The narrator of this graphic novel says: “I don’t know why I feel so nostalgic when I think about these things. In many ways, that was a dark and hostile Spain. And, despite everything, I was so happy that I almost feel guilty.” And there, more in memory than in reality, is where Ronson and his ochre-coloured portrait of rural Spain in the 1960s has become a phenomenon. It is already being called an instant classic: five editions, a translation into French and consecutive awards from the comic fairs of Barcelona, Valencia and Tenerife, as well as prizes from the Spanish comic critics’ association and El Ojo Crítico.

César Sebastián, 35, is not intimidated by being put in front of a tape recorder. He himself did it with his father. Without realizing it, he would turn on the recorder on his mobile phone and ask him to tell him about his childhood memories in Sinarcas, a town of a thousand inhabitants nestled on the border between Valencia and Cuenca. In long conversations in the rearview mirror, his father gradually unfolded that mythical universe normally embellished by the sieve of bucolicism and nostalgia. But there was more. There were beatings to children at home. There was sexual repression that led to “going to the window” to spy on girls in their room. There was normalized animal abuse. There were nicknames in a world of mellaos y mataliebres. There were, above all, people who thought that their lives did not deserve to be told. And everything that his father told him without knowing that his son was recording it has nourished César Sebastián’s journey into the memory of a father and a country: the backroom of the villages that the summer now lights up.

“Memory is complex,” reflects the illustrator, “it has a collective dimension, that of the story of the past that we tell ourselves as a society. That is why collective memory is always in dispute and in permanent rewriting: because of its high political value. And then there is the individual dimension of memory, which constitutes the framework of our own identity. In some cases what we remember is true, in others it is very unreliable. And that mysterious dichotomy – what we remember and what we don’t, what is true of what we remember and what is not – is what interests me most about memory. The traps of memories. How we fill in the gaps left by oblivion. How what one contributes to that filling says more about our present self than about our past self. Because deep down, we all remember to try to understand ourselves better,” says César Sebastián almost in one breath.

He has tried to distance himself from false nostalgia and pastoral atmosphere. He knows what the rural world is like. He knows it well. He grew up in the village of Landete and lived there until his adolescence, when he preferred his life to smell of fanzines, comics, Fine Arts and exhibitions in Valencia. “The idealization of the rural world always starts from an external view. An urban view that associates the rural with summer holidays and bucolic landscapes, but ignores everything that is unpleasant about life in the village, which is a hard life, with a certain abandonment, few opportunities and the supervision of your life in a closed community that sometimes does not digest the different well.”

All these aspects also permeate Ronsonwhere he avoids idealization. He also avoids drama. Rather, he chooses a path that is not often traveled in the rural approach: the contained fascination with the ordinary. “It only takes distance, in time or place, for a normal or dull reality to seem extraordinary to us. And the life that my father described to me was a shock “It was a constant for me. For example, the proximity of the children to the old people who played games in the bar; wandering around the street with absolute freedom; the austerity of a world where there was almost nothing; the unpunished and normalized violence towards animals, towards children, towards women behind closed doors at home. I heard him speak and everything amazed me,” he explains.

But he noticed a minor detail. An old coin called—nobody knows why—a ronson. The ronson was smaller and heavier than a normal coin. His father used it as a child in the game of black coins: coins were placed in the center of a circle and, by skillful throwing of other coins, they tried to get them out of the circle. Whoever got them out, took them. That ronson that his father still kept has worked like the rosebud of Citizen Kane: a trigger for that lost childhood, recovered with this book.

Sometimes they are metaphors, like the images of a tree that grows until it is reduced to a mere felled trunk and full of roots, as many rural emigrants felt in Spain in the sixties. Other times they are questions in the narrator’s voice. Like this one: “Lately I wonder if I am still able to enjoy the good times while I live them or if, on the contrary, I am condemned to miss them once I have left them behind. I suppose that back then I was not so obsessed with time; uselessly planning the future, constantly looking back and, paradoxically, trapped in the present.”

In the pages of Ronson There are abandoned houses, cracked walls, dilapidated vehicles: but that is not what dominates this tricolour frieze – ochre, black and white – of yesterday that preceded the current depopulation. There are also echoes of Miguel Delibes and the Clam by Luis Mateo Díez. Also the visual eagerness of the Italian neorealism of Rossellini and De Sica. Or that of Death of a cyclist, Main Street o Grooves. Everything shines with the calm of a naturalistic style and a clear line of drawing. Refined. Without visual noise. Almost transparent. Austere and detailed. Reflective.

Can that national-Catholic world without democracy generate nostalgia today? It can. “Nostalgia is a deceitful re-reading of the past. One is capable of feeling nostalgia for the most absurd or crazy things,” says César Sebastián. But it is not the focus of Ronsonwhich began with a son secretly recording his father’s voice with his old stories. Three years later, when the son finished the work and the book was already printed, the father – Julio César Sebastián – waited until he was alone. In the dining room. In the quiet of the night. Then he opened the first page. It said: “The other day, for no apparent reason, Uncle Constancio’s wine cellar came to mind. Now it’s a ruined building and weeds have made their way everywhere, but I still remember what every corner of that place was like. How many hours I spent there playing when I was a kid.”

The man, who is approaching seventy, continued reading. Alone. In silence. He read the entire book in one sitting. He was deeply moved. A few days later he gave his son a present. It was a coin with the effigy erased that no one knows where it came from. A piece of copper with a whole world attached to it. It was the ronson. rosebud of a deceptively happy world.