Despite the deliberately disruptive desire of 20th century art, it is always possible to build bridges between the avant-garde and the historical past in which they were rooted. It is evident, for example, in the respect that artists like Klee and Picasso, two Pablos and icons of their time, showed to the traditional genres of painting: portrait, landscape, still life, nude. The new Thyssen Museum exhibition revolves around these four themes, Picasso and Klee in the Heinz Berggruen collection (from October 28, 2025 to February 1, 2026), the second “great duel of the titans” of the season of the Madrid institution after having inaugurated last week its particular vis-à-vis between the two emblematic artists of pop art and abstract expressionism: Warhol, Pollock and other American spaces.

While this last exhibition could be interpreted, as the museum director, Guillermo Solana, pointed out in the presentation to the media, as a proposal of “panoramic effects and large impressions”, the comparison between Picasso and Klee requires a more “careful” reading on the part of the viewer, since the associations established seem more “subtle and can only be appreciated very closely and very slowly.” Curated by Paloma Alarcó, head of Modern Painting at the Thyssen Museum, and Gabriel Montua, director of the Berggruen Museum in Berlin, the exhibition also brings together the legacy of two prominent European collectors: Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza (1921-2002) and Heinz Berggruen (1914-2007), whose collections have gave rise to two public museums in Spain and Germany, respectively.

Solana mentioned the “great duel of the titans” as a joke: when he was dedicated to art criticism, the editorial team titled a review that way and that gave him “terrible shame.” But, although the expression is hackneyed, it is not lacking in truth: those of Paul Klee (1879-1940) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) were undoubtedly major names of the first half of the 20th century, the first associated with movements such as surrealism and expressionism and, the second, the initiator of cubism that would shake the patterns of art. Almost like “opposite figures,” as Alarcó added, Klee started from a point of view more rooted in the mentality of northern Europe, “intellectual and musical.” Picasso was, however, Mediterranean: “earthly and intuitive.” The man from Malaga was also more inclined than his colleague to monumental formats, but this exhibition mainly presents small-sized works often made on paper, given that both artists, as Solana stressed, “were passionate draftsmen.”

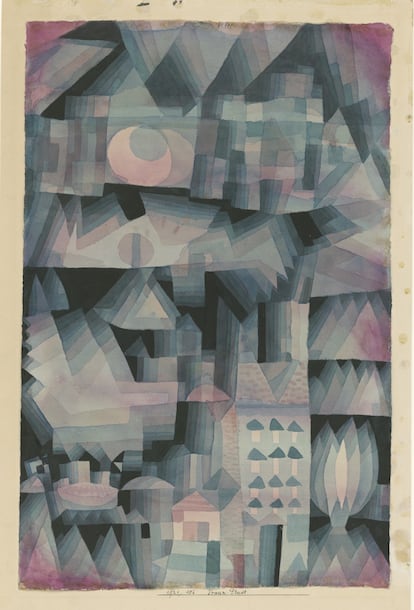

Spread across four rooms on the first floor of the museum, the exhibition opens in the room dedicated to portraits and the concept of the mask understood “as the great revolution of the genre,” according to Alarcó. With it, the portrait broke its association with the concept of mimesis and masking awakened new magical and hidden meanings in the representation of appearance. If in this section the contribution of Picasso stands out – who, not in vain, was “one of the great portrait painters of the 20th century” – in the next stop, the one dedicated to landscapes, it is the voice of Paul Klee that resonates most strongly within the four walls. The sensational landscapes of invented cities created by the Bauhaus professor share the same fixation on geometry displayed in his still lifes in the third room of the exhibition, the one dedicated to objects. At the end of the route, several works of harlequins are exhibited alongside the nudes, a circus theme that Picasso devotedly cultivated but that Klee also addressed, and that coincides with the nude in his interest in anatomy.

Some old paintings from the Thyssen collection have been placed in the different rooms that highlight the historical continuity of artistic practice: for example, a View of The Hague (ca. 1690) by Gerrit Berckheyde in the landscapes section or the wonderful fountain nymph (ca. 1530-1534) by Lucas Cranach the Elder in the part dedicated to the nude. Although the pieces by Picasso and Klee on display come largely from the Berggruen collection – whose museum, which is part of the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, is closed for work – there are also several that come from the Thyssen collection and that at some point passed through the gallery that Heinz Berggruen ran in Paris. In fact, the famous Harlequin with mirror (1923) by Picasso, which today is guarded by the Madrid museum, once hung on the walls of the Berggruen family home.

Heinz Berggruen’s son, Olivier, participated in the presentation event, where he said that his father began building his collection in 1940 with a watercolor by Klee, and that little by little he added the works of a handful of creators whom he considered essential to modernity: Cézanne, Seurat, Matisse… and, of course, Picasso. “He didn’t collect many artists, but rather he collected deeply,” said Berggruen, who confessed that his father had “a complicated relationship” with Picasso’s late work, “although in the end he ended up collecting it.” Also complex, to put it an adjective, was the way in which Picasso and Klee met, back in October 1937: the Spaniard was invited to the Swiss-German residence in Bern, but as his train arrived early, he entertained himself eating and drinking and ended up arriving late for the visit, something that was not exactly to the liking of his host. In that meeting, as Alarcó related, Picasso picked up a work by Klee and began to turn it over, not knowing if he was placing it face up or face down. As a metaphor for the world they had lived in, Klee said something similar to this: “You can look at it wherever you want, because everything is upside down.”