An Iranian girl looks ahead, arms crossed. She wears the veil, and a certain firmness in her eyes. Just two vignettes later, we see exalted men and women, protesting with raised fists: the Islamic Revolution begins. Those drawings, which began in the year 2000 Persepolis, they changed the history of that little girl, of the graphic novel and, perhaps, even of Iran. So much so that for years Marjane Satrapi (Rasth, 54 years old) continued to be asked to portray that young woman, to which she responded again and again: “she has grown up.” She has become a woman. Comic legend. Filmmaker. Franco-Iranian. Fierce opponent of the regime of her country. And now, the Princess of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities, as announced this Tuesday by the foundation that awards the awards.

The jury highlights Satrapi as “an essential voice for the defense of human rights and freedom, a symbol of civic commitment led by women,” and describes her as “one of the most influential people in the dialogue between cultures and generations.” and remember that in “Persepolis “It exemplarily embodies the search for a more just and inclusive world.” That is to say, the award recognizes many things at the same time, exactly what Satrapi’s works represent. Above all, the talent of a narrator capable of learning and mastering new formats. She had hardly any experience, other than having only been at the Strasbourg School of Decorative Arts for a short time, when she built her masterpiece. She believed that she would never find a publisher, that it would all end up being little more than photocopies for her friends. It became a milestone for comics “only comparable to the Maus by Art Spiegelman”, according to Reservoir Books, the publisher that publishes it in Spanish, Basque and Catalan.

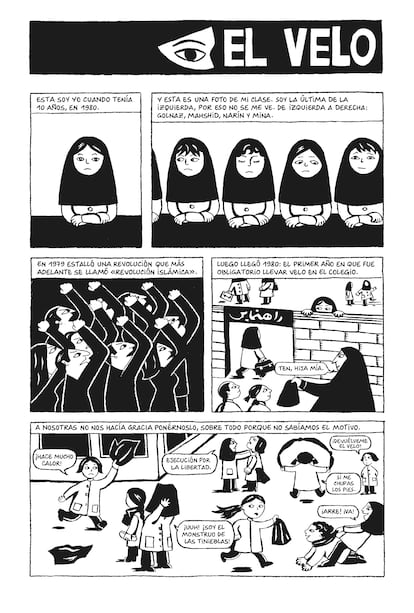

Why Persepolis She draws on her childhood in Tehran during the Islamic Revolution that, in 1979, overthrew the Shah of Persia and brought Ayatollah Khomeini to power, until the beginning of her adult life with her arrival in Europe, where her parents sent her and she has resided since then. Satrapi’s family, wealthy and progressive, initially sympathized with the revolution, but when it was dominated by Islamist sectors it led to a theocratic regime that restricted individual freedoms and embarked on a war with Iraq in 1980, under the surveillance of the Guardians of the Revolution. All this is narrated in Persepolis, but the black and white of the drawing also serve to trace all the grays of such a complex event: the macro-story, between ecstasy, repression, prison and deaths, along with daily life and the perspective of a teenager who longs for both freedom and a Kim Wilde cassette on the black market.

“Drawing is the first expression of the human being, prior to writing,” she said about choosing the comic. And Satrapi didn’t know much about cinema either when he let himself be convinced to adapt Persepolis to the screen, four hands with Vincent Paronnaud. Received equally the Grand Jury Prize at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival and, then, the first nomination of a female creator for the best animated film in the history of the Oscars. Later, she filmed the road movie in Spanish sauce The Jotas band, The Voices, about a killer in the deep United States, or the recent Madame Curie.

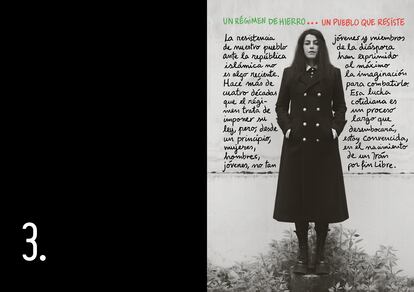

But the Princess of Asturias also exalts the courage of a voice always ready to shout for justice and against oppressive power, in her statements and interviews, as in her art. So much so that she recently returned to comics for the first time in years to coordinate Women. Life. Freedom, anthology where she has brought together stars like Paco Roca and Joan Sfarr – a kind of “international comic brigade”, in her definition – with Iranian authors like herself or Shabnam Adiban, to support the protests that are shaking their country and denounce the repression that citizens suffer. All since the death, on September 16, 2022, of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old girl detained by the morality police for not wearing the mandatory veil for women in Iran. Satrapi has insisted several times that there is only one word to explain what she boils in her country. Neither “revolt” nor “movement”, but “the world’s first feminist revolution.”

She was equally clear in qualifying the other front. “This regime does not love Iran. They don’t dress like Iranians or talk like Iranians. “Iran gives them the hard time,” he told EL PAÍS in November. “They are a minority and do not represent even 15%, and among them are the religious lunatics, but also a large part of people with economic interests,” he added. His choice is therefore evident in another difficult debate: there are Iranian artists who have stood up against the Government and have paid a price for it, such as the director Jafar Panahi, sentenced to six years in prison for propaganda against the regime. Others, like filmmaker Asghar Farhadi, have been accused of profiling for years. Satrapi has belonged to the first camp for decades. Somehow, with Persepolis, He even showed the way.

“I sold millions and I don’t know how many hundreds of conferences I gave. Did I change something? What do I know? Did I arouse people’s curiosity? Yes. I contributed a little. Just a little bit, although that’s the only way to change the world,” she reflected in November. Because, at the same time, Persepolis It contained other fundamental keys for Satrapi: a realistic portrait of the country and its people, far from the frames of “hills and donkeys” or the image of a nation “trapped in dark times” that Western festivals look for in Iranian art, as he lamented. a month ago The Guardian. There is another key word, one of the most repeated in his interviews: “Decency.” That of not wanting to give lessons or suggestions from afar, but only support and a speaker, to his fellow citizens who fight every day in Iran. And not to complain despite decades without visiting your home, because there are others suffering greater tragedies.

All of this has guided his work, his career and his life. With the same decision she opposes a dictatorship, being photographed, or being locked in a category. “I make both the films and the books with this part of my body (the head). My tits and my sex have nothing to do with this. If I am appreciated I want it to be as a filmmaker, not as a man, woman, hermaphrodite. If there are festivals for men and women, let’s make them for blacks and whites. Or short and tall, because if you are 1 meter 10 or 1 meter 50, you will not have the same vision of the world. They are ghettos! “This feminism doesn’t interest me at all,” she told EL PAÍS in November. With the same freedom, she smokes one cigarette after another or clarifies her position on one of the most controversial aspects of Iran: “The veil is a symbol of women’s submission. It means saying: ‘I am a sexual object, I must cover myself because, if not, the man will have an erection.’ And it starts at six years old, because at that age she can already excite a man. Taking it away is important, but neither the left nor the feminists in the West support us, because they have gotten it into their heads that Islam and Muslims were the same: if you attack Islamism, you attack Muslims. And, at the same time, in another interview, she declared: “As I consider that human rights are superior to my personal point of view, I will fight so that (women who want to) can wear the veil even if I hate it.”

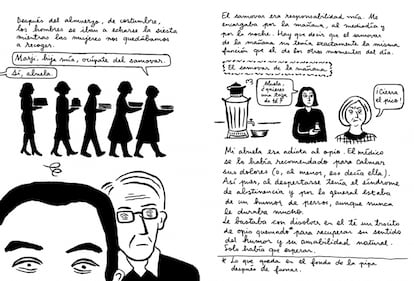

Among his other works are Embroidery, which tells the lives of Iranian women, and Chicken with plums, also adapted to film by its author. This work recounts the last eight days of the life of a relative of Satrapi named Nasser Ali, a well-known player of tar, the traditional Iranian lute. “She has been a followed, respected and loved author in our country for two decades, with hundreds of thousands of loyal readers who continue to grow day by day. We are proud to be the publishers of Persepolis, a work that is already an icon of universal culture, but his other two graphic novels are no different in quality and mastery,” says Jaume Bonfill, editorial director of Reservoir Books. Satrapi’s voice has been heard for years. The girl of Persepolis has grown. She has changed. But believe and fight just like then. Or more.