The most fascinating poet of the 19th century, Arthur Rimbaud, did not sell a single book during his lifetime. The most important writer of the 20th century, Franz Kafka, did not even publish his books. However, Miguel de Cervantes became a popular phenomenon five minutes after the first part of the book went to press. Quixote in 1605. Everything fits in the mysterious vineyard of literature. This ancient work of writing stories and building beauty with words is so prodigious.

After the Second World War, the figure of the professional writer, unprecedented until then, was consolidated in Europe and the United States. To the person writing this it seems that the professional writer only exists in advanced democratic societies, with a high level of prosperity. But it is true that this figure is recent and raises suspicions.

As a result of David Uclés winning the prestigious Nadal Prize a few days ago, a whirlwind of opinions, in the press and online, has come to entangle the old issue of whether novelists who sell books are bad and those who don’t sell are good. Spain is a country that voluntarily deserts rationality whenever it can. We see it in politics, of course. The amazing thing is to see it in literature as well.

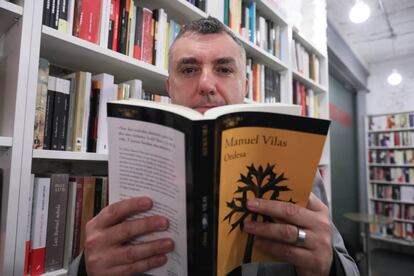

Literary criticism in Spain is also emotional. It is impossible for the critic to avoid the sociology in which a novel is involved. To Uclés with the successful The peninsula of empty houses The same thing has happened to me with Ordesa. When these novels had barely reached bookstore shelves, some critics fervently supported them, convinced that they would be works that were as much masterpieces as they were minority works. When they became popular works they withdrew their support.

That’s what Nadal Suau did with Uclés’s novel and with mine. Celebrate a novel that housewives and retirees read in reading clubs in empty Spain, never ever, dead rather than simple. Critics have to build their own house brand, their divine personality. It is the old fight between the popular and the cultured. And it is also the emotional disorder that the triumph of literature produces in a certain critic, as it ceases to be their property and its government passes into the hands of the common reader, so despicable for the intelligence of the chosen ones.

However, we are talking about the triumph of literature, in an appeal that José Carlos Mainer used in a recent essay when talking about the poets of the Generation of ’27. What was the Generation of ’27 really if not the triumph of literature? Federico Garcia Lorca is not the heritage of the hundreds of specialists in the academic world. Lorca belongs to everyone. Literature, very occasionally, breaks into bookstores and prevails over commercial books and is capable of selling thousands of copies.

This benefits every writer who tries to build novels with a solid literary intention. However, this is not the case in Spain, this country of all devils, where the success of a literary novel quickly removes it from the adjective “literary.” You always have to celebrate when books with a literary intention, whether you like them more or less, or even if they blow your mind, sell in the thousands. It has its comical point, since if literature does not triumph from time to time we will be left without booksellers to recommend it, without editors to edit it, and without literary supplements to comment on it; and two great critics like Nadal Suau and Ignacio Echevarría would be left without a job.

Literature, very occasionally, breaks into bookstores and prevails over commercial books and is capable of selling thousands of copies.

I remember that in his day Echevarria openly lamented the success of Patria, by Fernando Aramburu. And I remember that Nadal Suau called the exceptional novel a failed book A lonely walk among the people by Antonio Muñoz Molina, a book that in France should not have found anything unsuccessful when it won nothing less than the Medici Prize, one of the most coveted awards in international literature.

Failed in Spain; exceptional in France. It has its comedy step, of course. Of course literature happens somewhere else, it almost always happens in the desperate and lonely heart of a writer. That was always its place, but from that heart literature begins a long journey to the most unexpected regions of life, politics and history, and that journey is beautiful, and to censor that journey is to not have understood that literature ends its journey and the meaning of its being in the eyes of a reader who suddenly falls in love with the page of a book.

I owe it to my readers, said Miguel Delibes, and he was right. My readers give me freedom, said Almudena Grandes, and she was right. In literature, 50% is put by the writer and another 50% is put by the reader, Javier Cercas always says, and he is right. Readers, my friends, are literature. Let’s dust off the almost dying value of tolerance. Let’s tolerate all books. All books matter. Those that sell a hundred copies and those that sell a hundred thousand and those that sell ten and those that sell ten million.

Literature almost always occurs in the desperate and lonely heart of a writer.

Let’s read as many as we can. Now, yes, in capitalism the best you can do for a book is buy it. And then, if you’re lucky, read it. But first buy it. And let’s not be hypocrites or corny romantics: writers need to eat three times a day. Let’s not starve them, they sweat their share in front of computer screens. Let us love books with a passion, and let us always celebrate the triumph of literature over ignorance and history.