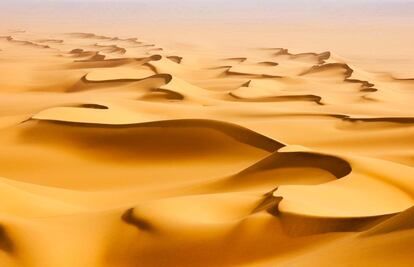

As chance or fate would have it, the current resurgence of the painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, author of Thumbs down, via Gladiator II y Those who are going to dieI have coincided with the wonderful arrival, as if the simun, the give me or the khamsin I would drag it, of desert sand. And not from just any sand but one from the Great Sand Sea of the Libyan desert, the land without maps, the extensive properties, of course, and forgive me for the loop from which I think I will never get out —Al-Hamdu night!thank God—, by Count Almásy, the explorer protagonist of The English patient. Among Gérôme’s famous paintings, apart from those of gladiators and chariots like the aforementioned Thumbs down, Course de char or the terrifying The re-entry of the felineswith its full lions, tigers and panthers and its charred crucified men, there are some that especially move me, such as Bonaparte in front of the Sphinx y Napoleon and his generals in Egypt (which must have also inspired Ridley Scott, I say). But above all I love it Queen Rodope observed by Gyges (1859), which recreates the famous and morbid episode of the Lydian monarch Candaules that Herodotus narrates in book I of his History and that appears in The English patient (Michael Ondaatje’s novel and Anthony Minghella’s subsequent film).

“This Candaules,” says the great Greek historian with his best tone for gossip and the scabrous, “was in love with his wife and, as a lover, he firmly believed he had the most beautiful woman in the world,” so he kept telling her about it. to his favorite officer, Gyges, a great spearman apparently. Thinking that he didn’t quite believe it, he told him: “Try seeing her naked.” Convinced that he was in deep trouble—as he was—Gyges tried to reject the unusual offer. But the king insisted, and the reluctant voyeur ended up hiding in the royal bedroom, where he watched, swallowing saliva for various reasons, as the queen (Herodotus does not give her name but according to other sources her name was Nisia or Rodope) was shedding her clothes. clothes until they are stripped down (sic), the last linen garment, which was later also taken out.

Taking advantage of the fact that Candaules’s wife turned around and headed to the bed where the king was waiting for her, who must have been very upset by all this, well, if not what (in fact history has given its name to a sexual practice, candaulism, getting excited by seeing your partner undress in front of another person, which is already a curious vice), Gyges ran out of the camera, although not before she discovered him. The next day, the queen, angry with the whole operation (Herodotus points out that among the Lydians “being seen naked is a great humiliation, even for a man”), presented the officer with two radical options: “Either you kill Candaules and You take over me and the kingdom, or you are the one who must die without further delay to prevent, from now on, by following all the orders of Candaules, from seeing what you should not.”

Giges, voyeur despite himself, He very intelligently chose to preserve his life, and that night, “in the same place where he exposed me naked,” the queen hands a dagger to the officer, who kills the king while he sleeps, and, says Herodotus, “he took the woman.” and with the kingdom of the Lydians.”

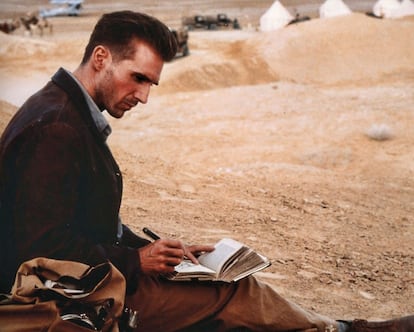

In The English patient where the episode takes on a very different meaning as a preamble to a captivating romantic relationship, the trio is made up of the rich Geofrey Clifton, his wife Katharine (they are newly married) and Count Almásy. The three are part of an expedition in the Great Sand Sea and the husband does not stop singing the excellence of his wife and how in love he is with her, leaving us a new word, “uxoriosness”, excessive love for one’s own woman. But Katharine, who has asked the explorer count for some reading (which is never a good sign on a wedding trip) and he has ended up leaving her annotated Herodotus, without which she never goes to the desert, reads during a party in the dunes the Candaules passage. And Almásy points out in Ondaatje’s book, magnificently summarizing the novel: “This is the story of how I fell in love with a woman who read a certain story by Herodotus.” When things start like this you can’t help but end up in a room in Cairo looking for Almásy’s Bosphorus (the vascular synoid, the little hole in the neck) while it plays on the record player Love, love, that melancholic Hungarian lullaby, and you evoke the burning flight over a lost oasis. In the film, with a script by Minghella himself (I have it on my nightstand next to Ondaatje’s novel, my Herodotus and certain Almásyan fetishes), there are some variations of the scene of the reading of the Candaules episode. The explorers, at the Pottery Hill camp, the script specifies, play around a bonfire to spin the bottle with an empty one of champagne and the task is to recite something. It’s Katharine’s turn (Kristin Scott Thomas) and she tells the story of Candaules while Almásy (Ralph Fieness) fixes his eyes on her. A paragraph to remember that in The English patient other readings come out as beloved as Anna Karenina, Kim y the last of the mohicans. The first two have plot logic (Tolstoy’s novel obviously, Kipling’s because of the presence of Kip, the Sikh sapper); The third one, the truth is, it’s a bit difficult to see, although I can’t think of anything more beautiful than having the adventures of Uncas read to the (supposedly) English patient.

There are other paintings that describe the central episode of the Candaules story, such as that of Jacob Jordaens, with a very Rubensian king’s wife, from 1646, or the controversial one by William Etty, an author much better at painting butts than arms, known very accurately as The recklessness of Candaulesfrom 1830. But for me, the best without comparison is that of Gérôme. I have become so obsessed with the painting that on one occasion I went to see it where it is kept, which is quite far away: the Ponce Art Museum, in that town in Puerto Rico (how Gérôme’s Candaules ended up there would deserve another chronicle). I crossed the entire island with the Spanish consul Eduardo Garrigues to see it, but it turned out that it was in the warehouse and there was no way for them to get it out, so we had to console ourselves (!) with the contemplation of June blazing sunLeighton’s dazzling work and the museum’s collection of Pre-Raphaelites.

There are also other literary revisions of the Candaules passage (and a Petipa ballet!). Plato collects in his Republic the legend that Gyges possessed a ring that made him invisible, which would have saved him a lot of trouble in Herodotus’ story. But the two most interesting and elaborate versions of the story are those of Théophile Gautier (King Candaule,1844) and the one included by Mario Vargas Llosa in his stimulating Stepmother’s Praise (1988, Tusquets, The Vertical Smile). Gautier tells it with a wild orientalism dripping with romanticism that moved Victor Hugo himself. The wife of Candaules (Nisia, daughter of the Persian satrap Megabaze), who appears mounted on an elephant and covered in clothing and jewels, is described as a goddess whose barbaric modesty prevents her from revealing herself to anyone other than her husband. In Gautier’s story, Giges, “le beau”, the beautiful one, has seen her before, since a gust of wind had briefly revealed her face. To remember a phrase from the French writer: “Women are only given to those who do not deserve them.” Candaules suffers because by only being able to see his wife, no one knows what treasure of beauty he possesses (that very masculine attitude that is essentialized in the joke about the castaway and Claudia Schiffer). And he seeks the confidence of Gyges, whom he introduces to the royal chamber, where the queen’s involuntary striptease occurs. “He dropped his robe and the white poem of his divine body suddenly appeared in its splendor, such as the statue of a goddess whose wrappings are removed on the day of the inauguration of a temple.” And Gautier points out, unable to describe more: “There are things that can only be written on marble.” In the story, Gyges is so impressed by Nisia’s vision that it does not take him much to convince himself to kill Candaules (“meurs ou tue!”). She, it seems, wasn’t immune to the officer’s allure either. Once the king, the last of the Heraclids, was eliminated, Gyges took on the crown, established his own dynasty, and, Gautier says, “he lived happily and did not let anyone see his wife, knowing what it would cost him.”

What Vargas Llosa does, a declared erotic genre, is very different. The Candaules passage appears, along with other classic episodes represented in art, in the middle of the morbid story of the couple formed by Don Rigoberto, his wife Doña Lucrecia (the stepmother of the title) and the former’s child, the clever and disturbing Alfonsito, Fonchito, advanced voyeur and of a perversity that leaves astonished and refers to Bataille. The Candaules that the novelist recreates, with his unsurpassed prose, reflects Rigoberto’s interest in his lady’s behind and what he boasts to Gyges is the queen’s rotund “rump.” Vargas Llosa, fortunately for those of us who fetishistically venerate Herodotus’ version and Gérôme’s painting (not to mention the echo in The English patient), refers to Jordaens’ painting in his thuggish and sycalyptic story, dedicated to Berlanga.

I said that the memory of Candaules that gave rise to these many lines came to me with a blast of sand from the Libyan desert. It was sent to me by Ángel Carlos Aguayo, who has been there with his things. The golden sand, in which I dug to see if the lost army of the Persian king Cambyses was buried, which Almásy searched for so much, came packed in a bottle of Egyptian mineral water of the brand Shiva, which comes from the springs of the famous oasis. Siwa is the oasis of Amun, famous in ancient times for its oracle and often mentioned by Herodotus. And it is where the Bedouins take the English patient (Almásy) burned after falling with his burning plane into the Great Sand Sea. Ángel Carlos has added another bottle of Siwa to the shipment (Natural Water from the Siwa Oasis, it says on the label), this one with the original water, with the nice suggestion that I use it to baptize my grandson Mateo. I can’t think of a better idea: a baptism of adventure and legend, with Herodotus in the readings, and Count Almásy as godfather.