Josele Santiago lives under great uncertainty: he does not know how he will react when he faces a stage again to offer a concert and exercise his profession, that of a musician. His last recital dates back to October 2024. He climbed the stairs, stepped on the platform installed in the Bullring of Caravaca de la Cruz (Murcia), “and it was like being on another planet,” he explains. “I was playing and I couldn’t hear the music. I heard noise and saw lights, but I didn’t know where I was. A terrible thing. I wanted to continue, and then Fino (Oyonarte, bassist of Los Enemigos) came up, saw how I was and, with good judgment, told me: ‘Let’s go, Josele, let’s go.'” The next day, Los Enemigos released a statement announcing that all tour dates were cancelled. “Josele is dealing with a series of health problems whose treatment is affecting him physically and especially mentally more than expected,” they reported.

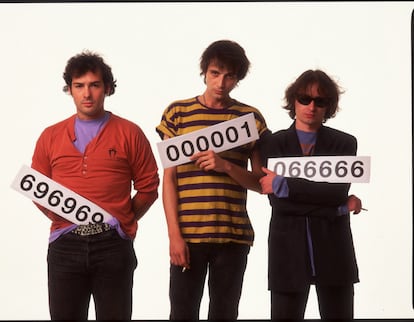

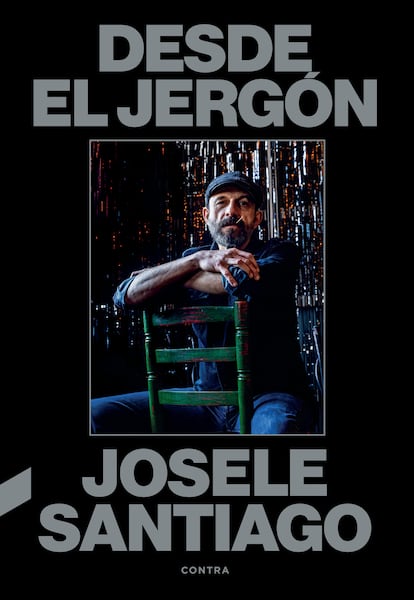

Sitting in a bar in the center of Madrid, his city, although he has lived in Catalonia for 16 years (“Things of love,” he indicates), Josele (60 years old) brings out that dry remark so much his that it permeates the many dramatic episodes of his life and some of the 200 songs he has composed: “Knowing my history, people must have thought: ‘This guy must have gotten into it…’. But none of that. It’s about stage fright. At my age…”. The year 2025 was difficult for the brave musician: without income due to not being able to perform, he had to sell 20 guitars from his collection. He has only been left with three or four, “the unsaleable ones.” “With that money, an advance that I asked for from authors and a bite that I gave to a small financial cushion that I had, I have been getting by,” he concedes. Creatively, however, it has been a fruitful period: he has composed and recorded the new Los Enemigos album, which will be published in September, and has written his memoirs, From the pallet (same title as one of Los Enemigos’ most popular songs; Contra publishing house, on sale February 25), a book that is devoured because it is written with humor, passion and drama. Also because courage counts history of Los Enemigos, a group with four decades of existence, of great cultural and emotional influence and with Spanish rock classics such as September, From the pallet o The countdown; and because without intending it Josele has described in the book a generation that spent their adolescence and youth in the eighties in the city neighborhoods, boys and girls passionate about music who had to deal with the lack of understanding of their parents, the first economic crises in democracy and the scourge of heroin.

This is how Josele describes himself in his memoirs in the first half of the nineties: “I love going to the Revolver (famous concert hall/discotheque in Madrid) and listening to Nirvana, Sugar, Pearl Jam, Mudhoney or Soundgarden at full blast from the center of the floor and dancing up to my ears… Addiction has conquered the stronghold of your priorities. Your last stronghold, by the way. I am attracted to anything that “I hurt myself. I self-harm with cigarettes and bang my head against walls.” He weighed 50 kilos (and is a kind of imposing presence) during part of the five years he spent hooked on heroin. “Yes, of course, you could say I was a junkie. All I needed was my tracksuit,” he jokes over a black coffee and a glass of sparkling water.

He wears a beard and a cap protects his alopecia from the cold on a cold January morning in Madrid. His voice is unmistakably rough and deep, as heard in his songs. Look into his eyes, which are bright this morning, although he claims that he has barely slept because he spent the night reading. billiard players, by José Avello. “I don’t understand how this writer is not better recognized.” He has come to Madrid for a few days and is staying at his mother’s house (94 years old), in Puerta del Ángel, southeast of Madrid, where he, an only son, grew up. There and in the nearby neighborhood of Lucero. “I had a hard time at school, the Salesians, nuns and soldiers no less. Getting there was my mother’s thing, who is very religious.” They called him The Fool. Even the teachers. “They were going after me, because I had long hair and I liked music. They were radical, praying the rosary and singing the Face to the suneven with Franco dead. Over time I realized the trauma that school caused me. You are at a very receptive age and you have some ideas that are not good: punishment, sin, the Devil… In the end, they invited me to leave the center, and I was delighted.”

Arriving at the institute was a liberation, but there was a problem that plagued him for many years: his problem socializing. It was difficult for him to make friends and he did not like “the hippies”, which were abundant in his institute. It was the late seventies. He hated progressive rock, Emerson Lake and Palmer, Genesis, Yes. I preferred the album Fun House, of the Stooges. “I know the bass lines on that record by heart. It also changed my life when I heard the opening chord of A Hard Days Night, of the Beatles. After that chord you knew something good was coming.”

Life in the neighborhood passed between misdeeds and songs. He claims that at the age of 17 he was already an alcoholic. “Although, of course, I didn’t know. I had a whiskey at a party and I liked it so much that I drank seven more. What are we going to do?” At the age of 20 he started taking pills. He had just formed Los Enemigos. “They diagnosed me with anxiety and depression and prescribed me anxiolytics. Knowing how they knew I was an alcoholic and that I had no plans to stop drinking, I don’t think they should have prescribed them to me. Because I was a bomb: taking all those pills and drinking like a beast. My problem has always been addiction. I have been addicted since I was like that (and he puts his hand at a small height). According to my family, one day my mother dipped the pacifier in sugar and the next day I found the sugar. Since then I have always been like that. I become addicted to whatever. My illness is that I have a totally addictive personality, and that’s where everything comes from: depression, anxiety… “

He tells of his life with a tone of voice absent of dramas. He laughs frequently. Pause to reflect and then speak. In From the pallet highlights a Madrid rock that was made up of people like Cucharada, Leño, Asfalto, Mermelada, Topo, Burning, Moris (Argentine who knew how to sing to the capital like few others)… “Sometimes you get the idea that in Madrid there was no music at all before the Movida. Forgive me, before the Movida and its colors the panorama in Madrid was not as gray as it is painted. There were many groups doing things, despite the difficulties.” When the best years of Los Enemigos were going on, the Movida was already institutionalized and the groups earned generous amounts of money. While pop bands of that era boasted about playing just enough, Los Enemigos spent six hours a day rehearsing. “This thing didn’t seem even half normal to me. amateurismo: Man, if you’re in a group, at least tune up, and especially when they were earning millions hired by city councils. I also think that the whole issue of Madrid being the center of the universe has been greatly overstated. Yes, Andy Warhol came, but when he came he was no longer anyone. And I like things about La Movida, for the record: two of the best concerts of my life were one by Gabinete Caligari and another by Golpes Bajos. “Both of them in Rock-Ola.”

The musician makes it clear in his memoirs that Los Enemigos’ most celebrated album, life kills (1990), is not about religion, but about death, which he saw around him, with friends from the neighborhood who died from overdoses or AIDS. “I got hooked on heroin when I was 25, after recording life kills. There I realized: I have gone too far, there is no turning back. At first it was injected, but then I used the nose, because the silver paper gave me a bad feeling, and time has proven me right: the Chinese with the silver paper does much more damage, it is super toxic,” he explains. He stopped five years later after going through a detoxification center in the Community of Madrid. Now he reflects: “I am of the opinion that this is incurable. There are people who say yes, but I think no. It’s going to accompany me all my fucking life. “We have to accept it.”

In 1992, Lalo Cortés, a friend, representative and key player in the future of Los Enemigos, died in a traffic accident at the age of 28. Josele wrote for him The letter that does not… “If I have to choose a song from Los Enemigos, I choose that one.” This is how he defines the trajectory of his band: “We have not been in the first division or the second. We have earned our money as best we could. It has not been the typical rise and fall. Ours has been linear. We have never had a huge success and we have few followers, but very fans. The truth is that we have always been in a somewhat precarious way, but we have remained there.” The group remained separated for 10 years, during which time Josele launched his solo career, suffered severe depression and realized that his natural ecosystem is to be in a band, even more so when David Krahe joined Los Enemigos on guitar to replace Manolo Benítez. The group returned with a worthy solo album (Smart life, 2014) and a continuation at the height of his great works, beast, 2020. The next one arrives in September.

Josele gave up the last of his addictions, alcohol, 15 years ago. It was shortly after starting a relationship with the journalist Núria Torreblanca, whom he married in 2009. He dedicates several pages of his memoirs to her, proclaiming his love and thanking her for her help in the only drinking relapse he has had in 15 years. “This time I don’t have tremors or cold sweats or nightmares when I wake up. When I’m asleep, I do have them. Every day. But I also have Núria. I don’t know how she’s holding up, to be honest. I continue to appear regularly at the health center and I feel better. What I have the worst this time are the doors of bars. I try to avoid them, but sometimes it’s impossible. I can smell a glass of cognac from the street. Now that I don’t smoke, I can almost tell you up to the mark. Not much. Little by little I return to notebooks and guitars,” he writes in From the pallet.

The interview takes place in a bar, at his suggestion. The people around us began asking for coffees, but the conversation has lengthened and vermouths and beers appear; someone who had lunch early asks for sun and shade. “It took a long time for me to be able to enter a bar. It’s the golden rule: not even to order a coffee. Because you go to order a coffee and this phrase comes out of your mouth: ‘A whiskey, please’. And when you realize it, you already have it on the bar and there is no turning back. Better to avoid it. If I’m in company, like now with you, okay, but entering a bar alone is complicated.”

The meeting ends, but the musician wants this to be reflected in the interview: “With Jorge, from Ilegales, and Robe Iniesta (both of whom died last December), in addition to their music, we have lost a large part of the little lucidity that this country has left. What a shame not to have met Robe.” He also reports that before starting the Los Enemigos tour, probably in the fall, he wants to offer some acoustic concerts in the summer with David Krahe. There we will see if he has overcome stage fright. “I’m scared,” he says. “I don’t know what’s going to happen. But I have hope, because the rehearsals have gone phenomenal, the recording has gone very well. We’ll see…”