You have to have a great mastery of the photographic technique and a lot of sensitivity so that the image of a pepper or a toilet may seem like a torso or another part of the human body. The American Edward Weston (Illinois, 1886-California, 1958), a classic in the photograph of his country of the first half of the twentieth century, succeeded with his black and white shots, as can be verified in the retrospective with 177 photos dedicated to him by the Mapfre Foundation, in Madrid, until January 18, 2026.

The photographic exhibition that opens the season of the Foundation, entitled Edward Weston. The subject of formsbegins with a self -portrait of the photographer of 1908, who poses with one of the plates cameras with which he developed his entire work. Basically self -taught, he opened a study in 1911 and experienced in its beginnings with pictorialist photography, which tried to resemble painting. They are photographs of bucolic landscapes and staged situations. However, as explained by the commissioner of the exhibition, Sérgio Mah, “soon he saw that photography should not look at painting, but emphasize his own characteristics, so he expanded his imaginary.”

Urban, objects and naked landscapes passed, with sobriety and sharpness, through the Weston Chamber, which begins to make a name. What he seeks with his gaze are the forms, his roundness, as if it were a sculptor. Especially with the nudes, which seem to overflow the paper. It was the way to what was called direct photography, a new aesthetic arising in the United States of interwar, which sought a representation of reality with simplicity and clarity.

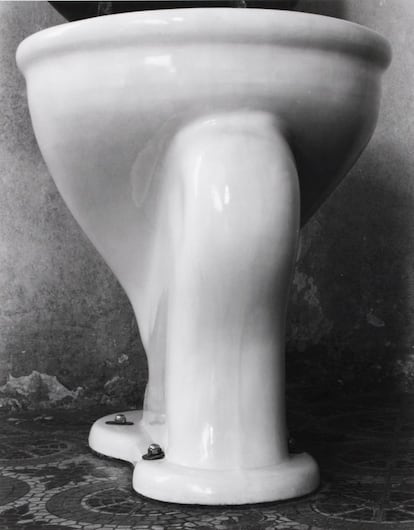

Mah attracts attention to photography called Toilet (1925), which Weston took in Mexico: “That bright and enameled receptacle of extraordinary beauty. There were the sensual curves of the divine human form,” the photographer wrote. Therefore, next to this white toilet, a naked torso confirms that for Weston the important thing were the volumes, the shapes, the curves, the folds, beyond that they are part of a sensual female back or a watter.

The commissioner pointed out the day of the presentation to the press, on September 16, that the vast legacy of this author is mainly found in the Center for Creative Photography of the University of Arizona, in Tucson. In that corpus the photographs of women have a significant weight, very important in their life and work, although the commissioner rejects that Weston was “a Don Juan, as sometimes he has been presented in his country, affecting too much on how that personal issue influenced his work.” Of course, Weston left his family and left for Mexico in 1923 with the Italian photographer and actress Tina Modotti, who had been her model before lover. While Modotti and other artists and writers participated in the effervescence of post -revolutionary Mexico, Weston remained foreign, leading his camera to anthropological themes.

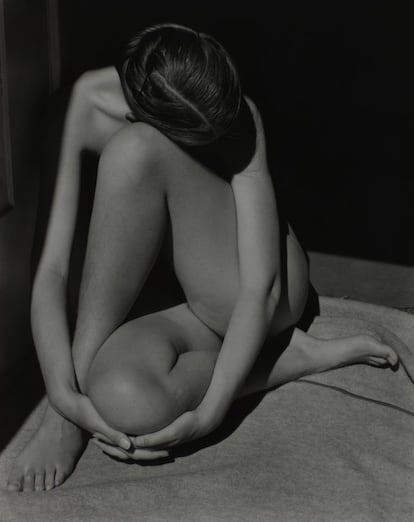

In any case, the Mexican experience opened its mind and was decisive in its trajectory. As explained in the exhibition, Weston then realizes that he has the ability to “transform the trivial into something suggestive.” “His instinctive way of seeing, which isolates the matter that interests and eliminates the unnecessary, becomes the essence of his talent.” After four years of relationship with Modotti, he returned to his country in 1926, where he resumed the nude series with commercial works. The best -known nude of his work did it in 1936 to which he was then his model, then wife, Charis Wilson, sitting with his arms around his legs and hiding his face and the pubic area.

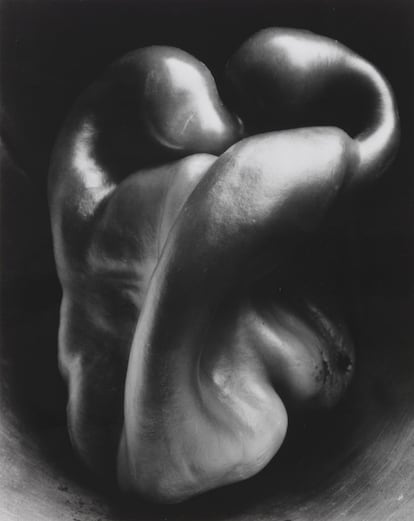

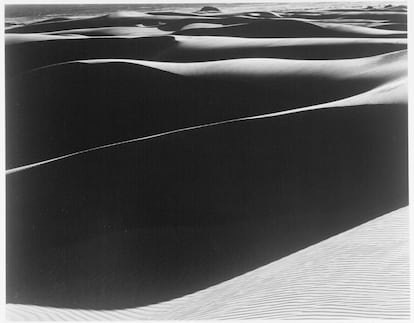

The exhibition, which, as usual in the Mapfre, has an extraordinary catalog (300 pages), continues with gangs of pumpkins, peppers, artichokes, mushrooms or marine shells … that under the meticulous Weston lens make the imagination fly to turn them into abstract, mysterious masses, which on other occasions are resembled to bodies that are twisted. As the photographer said, he wanted to “make a pepper more than a pepper.” That stamp continues in works on plants, trees and rocks. And the poetry of his series about Dunes, of 1936, of extraordinary beauty, in a black and white of great purity is striking.

In 1937, at the great moment of his career, with 55 years, he won the first scholarship granted by the Guggenheim Foundation to a photographer, who served to finance his emblematic book, California and the West. “Dare to be irrational,” he said, “stay away from the formulas (…) Our time is increasingly tied to logic, the mediocrity of mass thought, a dangerous shirt of force.”

Four years later he received a great commission, the visual portrait for a luxury edition of the classic Grass leavesby the poet Walt Whitman. However, the result of the thousands of kilometers and several states traveled for almost two years – a long trip in which Charis accompanied him, of which he divorced in 1945 – did not like the editor, who wanted something more literal that illustrated the verses. Weston had gone for free, with a more melancholic and decadent look. In the negatives that he took home, about 800, there were many of Louisiana and Georgia cemeteries, of abandoned or destroyed houses, garbage. “For the first time in his work there is disappointment and criticism of American reality,” says the commissioner. Only fifty images were published in the book. With the years and economic difficulties, despite the recognition of critics, Weston gave many of his photographs of that feeling of disenchantment.

From what interested him in photography and life, of women and their trips, he written many pages in his numerous newspapers: “Photography as a creative expression must be more to see. Seeing only means registering facts. Photography is not at all to see in the sense that they see the eyes. Our vision is binocular, it is in a continuous state of flow, while the camera only captures a single condition isolated from the moment”.

The indisputable thing is that after more than half a century of work, Weston “had contributed decisively to the photography to consolidate as an artistic medium,” says Mah. Weston, sick with Parkinson’s, who had removed him from photography at the end of the forties, died on New Year’s Day of 1958.