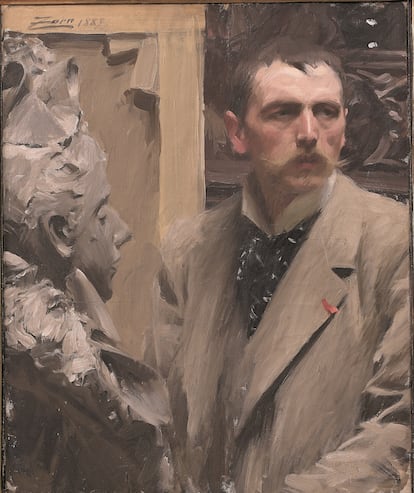

When he arrived at the reception of his hotel on one of his many trips to the United States – the now deceased told it Chicago Chronicle in a text from 1890—the staff asked the then well-known Swedish painter Anders Zorn (1860-1920) about his origins. The pale, mustachioed young man turned to his entourage and asked, “Where do I come from?” Someone suggested classifying him as a man “from everywhere,” but the proposal was rejected. Zorn turned to the employee and replied: “Nowhere.” Not a bad answer to describe a cosmopolitan guy who had traveled the world, from Egypt to Russia, from Palestine to Paris, from Central America to Türkiye. And yet, the most seductive thing about his exciting life was his fidelity to a peasant and rural past that any other artist in his elitist position would have hidden. That duality, which led him to be described by his circle as “half gentleman, half peasant,” permeates a work, forgotten for decades, which now stars in the first pictorial exhibition of the year at the Madrid headquarters of the Mapfre Foundation: Travel the world, remember history.

The exhibition, which will open on the 19th of this month and can be visited until May, brings together around 130 works by the artist and is the first retrospective dedicated to him in Spain. As the curator, Casilda Ybarra, explained well in the presentation to the media this Tuesday, “it is going to be a discovery for the public because it is very underrepresented in Spanish collections.” Actually, in the world. The Swede has long been the kind of enormously talented but forgotten artist who finds himself in the background of museum collections. Those works that are contemplated with brief pleasure on the way to the great names. The last time he was present in Spain was in an exhibition in 1992 that put him in dialogue with the work of his great friend, Joaquín Sorolla.

Of course, their reality was not always that, on the contrary. Zorn was a tremendously versatile artist who became an artistic reference in his time, from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th, with a production focused on nudes, society portraits and scenes of traditional Swedish life. And with a career, which the exhibition in Madrid presents in chronological order, also multifaceted. He began with watercolor, a technique that he ended up mastering and that occupied almost all of his first production until 1887. The Mapfre exhibition begins with one of them: In mourning, which at only 20 years old she presented at the Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm where she was studying and, as the curator explains, “it was celebrated as a breath of fresh air in the art scene.” A watershed in his life that “gave him the security and confidence to abandon his studies at the Academy, be a totally free artist and begin to travel the world.”

From the place I went, I learned. He came to Spain “attracted,” says Ybarra, “by that romantic image that had spread throughout Europe about our country. And, specifically, he was interested in the image of the Spanish woman.” He established a good friendship with Sorolla and Ramón Casas and fell in love with Velázquez, who ended up being a reference and source of inspiration for him. On at least one of the nine occasions he visited the country, he did so, according to what he wrote to his wife, because he missed the Sevillian teacher.

Then he settled in Paris—that’s a saying, because he didn’t stop traveling—in 1888 and went from watercolor to oil. “He was very aware that oil painting was the painting of the great masters and to measure himself in the capital of modern art he wanted to start working in this medium,” says Ybarra. And it didn’t go bad. His style, where very loose diagonal brushwork predominates and a very contained palette with a great command of light, led him to achieve great success almost immediately. “He received in Paris the greatest recognitions that an artist could wish for: the first medal at the Universal Exhibition of ’89, the Grand Prix in 1900, and the Legion of Honor. There he also had his great retrospective exhibition in 1986,” continues the curator.

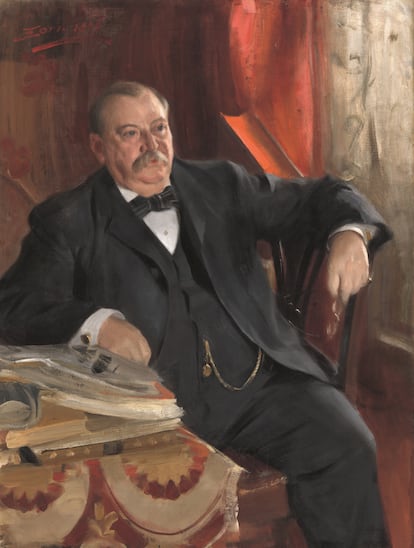

With this technique, and his consolidated image as a cosmopolitan, modern and international artist, he became one of the elite’s favorite portrait painters and ended up portraying dozens of great personalities: three American presidents—Howard Taft, Roosevelt and Cleveland—, magnates, aristocrats, actors and opera singers. He was also the great portraitist of Swedish society and its royal family. “In his portraits he bets on the individuality of his model by giving him an environment that is absolutely particular to him. They are works that have naturalness and spontaneity,” says Ybarra. A complete room in the Foundation reflects this. Also, although the exhibition does not focus on that, he is considered one of the great masters of engraving in the history of modern art and one of the revitalizers of this medium in Sweden.

But he never forgot his roots. That “from nowhere” that he referred to in the hotel was actually Mora, a small rural town in the center of Sweden that never tired of distilling its essence while commissioning portraits of the great personalities of its time and rubbing shoulders with the highest intellectual circle of society. His loved ones said that there, in a traditional Swedish cabin, away from ostentation, was where he was happiest. He returned every time he could and settled there permanently in 1896 never to leave again. “There he cultivated two of his favorite themes: that of bathers in Nordic waters and that of the popular traditions and customs of Sweden,” says Ybarra. Traditions that he saw were about to disappear and he wanted to freeze them to preserve them. “With that he headed a list of an entire generation of Swedish artists who promote the country’s identity through the revitalization of traditional culture and the appreciation of the Swedish landscape,” continues the curator.

What happened and how did it go from being a reference in the art world of its time, to being practically forgotten? “Basically, his work was relegated by the entire avant-garde revolution,” responds the curator. Just a few decades ago there began to be a resurgence of his figure and certain museums around the world have returned to him, in his native country, in Paris or in New York. The truth is that it is a unique and modern work. “It continues to touch on issues that challenge us today, such as our gaze towards the East or the representation of the female nude in the history of art,” Ybarra concludes. That double perspective that sustains his work, the global and the local, seems to resonate strongly again.