“Death in wars has a lot of work. Death in wars is never in a hurry. He takes some and leaves others for later. He left me and Corporal Villegas. He didn’t take anything from me, from Cape Villegas he took one leg, the left one,” wrote Miguel Gila in And then I was born. Memories for the forgetful. The legendary comedian from Madrid, who fought during the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side, in the Fifth Regiment of Líster, was arrested and put before a firing squad. At that point in the war, in 1938, Gila was not afraid of death. He was so exhausted, so devoured by lice, by hunger, cold, fatigue and thirst, that dying could be a liberation. But, as in some of his later stories, absurdity took over the situation: “They shot us at dawn, they shot us badly.”

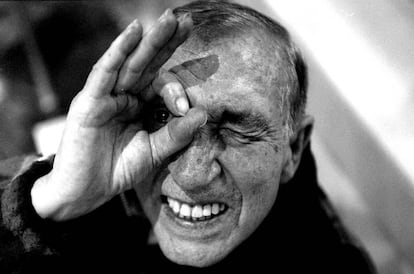

Death wanted to leave him for later. For much later: Gila died on July 13, 2001, at the age of 82, after having made his fellow regiments laugh with his jokes and drawings, and millions of Spaniards for decades with his monologues on the telephone, having the calm and rennet, the genius and the verve, of talking about war and its violence as a conquest of nonsense. From the now legendary “Is it the enemy? Let it be”, to the brutal “They killed my son, but we laughed”; from the sentimental “The war came at the time when it was worst for me,” to the demystifying “The war was not well organized. “They don’t let you know in advance.” A part of those reversals of tragedy, of those laughter of horror, are now part of the fiction film. Is it the enemy? Gila’s movie, directed by Alexis Morante and starring with grace and delicacy by debutant Óscar Lasarte, who gives his speeches that rhythm of phrasing and that accent so characteristic of the famous comedian.

Based on Gila’s book. Tragicomic anthology of work and life (Blackie Books), with a script by Raúl Santos and Morante himself, until now specialized in musical documentaries (about Enrique Bunbury, Alejandro Sanz, Camarón de la Isla, Héroes del Silencio and David Bisbal), but also with estimable children’s fiction, Oliver’s universe (2002), which combined the American cinema of the eighties with the Spanish idiosyncrasy, Is it the enemy? Gila’s movie It focuses solely on his younger years, between 17 and 20, with living in his grandparents’ house, enlistment and battle, leaving out both the painful post-war period, in which he suffered in prison camps and prisons, and his subsequent humorous career in radio, press (The Quail y Brother Wolf), theatre, nightclubs, cinema and television.

total comedian

Gila was the total comic artist, with an unusual humor that could be at the same time absolutely popular and have the subtlety of the most intelligent smile; intellectual, even. And although unequivocally personal, influenced by Ramón Gómez de la Serna and by the work of the authors of the “other generation of 27″: Miguel Mihura, Edgar Neville, Enrique Jardiel Poncela and company. A black humor based on the absurd, but tinged with a strange tenderness that made those harsh situations turn gray and even white. Spanish cinema, however, never took full advantage of it. Actor in generally short or very short roles in around twenty films, he only had a small handful of protagonists, among which stands out the wonderful The man who traveled slowly (1957), by Joaquín Romero Marchent (“Perhaps the only decent film I made,” he claims in his memoirs), which was also one of his only three scripts, along with The Ashen e Stories of love and massacre. With the episodic structure of a road movie, the script was signed by three people, including Gila and the director, but according to all sources the ideologist of each of the gags It was Gila alone, also the author of the drawings that accompanied the credits.

Now, his almost non-existent career could have changed with a little of the luck that he lacked in the cinema and that had given him in front of that firing squad in which the soldiers were too drunk to shoot and to worry about the terrible shot. of grace that they did not manage to execute. Gila was about to be the protagonist of the masterful My uncle Jacinto, of Ladislao Vajda, instead of Antonio Vico (he had to settle for a small role), and of the no less superb Placid, by Luis García Berlanga, before they decided on Cassen due to a lack of availability due to other professional duties. Of course, Gila never really liked cinema as a professional variant. As he says in his memoirs, after having freed himself from the early mornings of his time as a mechanic, it was hard for him to get up at seven in the morning and be taken “to a field full of flies, to eat a sandwich and an orange at 11 in the morning”, and that constant “Sequence eight, take 12” and “Wait a moment for those clouds to pass”.

Gila had already been bold enough on the night of August 24, 1951, when, fed up with what he defined as mediocrity, with no one buying his written monologues, and in a complicated economic situation, he decided to gamble heads or tails on the disappeared Fontalba theater, on Madrid’s Gran Vía, like a spontaneous man armed with a dirty old cape who jumps into the Las Ventas arena. He dressed as a soldier, managed to, once the play being performed was finished, get into the prompter’s shell, and come out there saying: “Please, Serrano Street?” The actor Fernando Sancho, almost holding back his laughter, managed to reply: “Excuse me: how do you say?” “Isn’t this the exit from the Goya metro?” Gila continued. “No, this is the Fontalba theater.” And what follows, already addressing the audience, was the first flame of a genius of Spanish monologue comedy: “I’m going to tell you why I’m here. I worked as an elevator operator in a warehouse and one day instead of pressing the button for the second floor I pressed a fat woman’s navel and they fired me. I went home and sat in a chair we had for when they said goodbye. Then my uncle Cecilio arrived with a newspaper that carried an advertisement that said: ‘For an important war you need a soldier who kills quickly.’ And my grandmother said: ‘Sign up, you who are smart.’

Wit, nonsense and tenderness. The rest is history. That of the man who traveled slowly. That of the man who was wrongly shot. That of the genius who always wanted to talk to the enemy. Let it be.