“Captive and disarmed the Red Army, the national troops have reached their last military objectives. The war is over.” This part signed by Francisco Franco put an end to the Civil War on April 1, 1939. Franco, as Generalissimo, would remain in power until 1975 and the different families of the right would dominate all layers of the State. They were the winners. The losers, on the other hand, would suffer repression and exile.

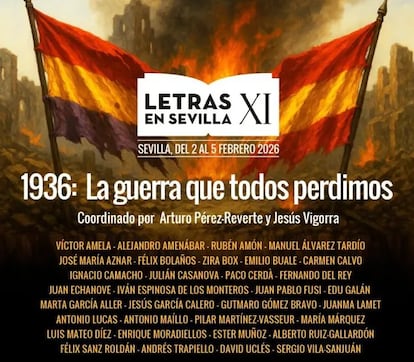

Between February 2 and 5, a series of talks with this title is held: 1936: The war we all lostcoordinated by Arturo Pérez-Reverte and Jesús Vigorra within the Letras festival in Seville. For 11 years, this initiative has brought together people of all political tendencies to debate issues that are often hot and divisive for society, such as migration, feminism or the political class.

Beyond the cultural interest, the event rose to the point of controversy this Sunday when the writer David Uclés, author of the best-seller The peninsula of empty houses (Siruela), which deals with the Civil War, announced his resignation from attending, mainly for two reasons. First, because he did not want to share the bill with former president José María Aznar and with the former general secretary of Vox, Iván Espinosa de los Monteros: “They have tripped up democratic values and measures that make us a modern and empathetic society,” Uclés told this newspaper. Other participants are Félix Bolaños, Alejandro Amenábar, Julián Casanova, Juan Echanove, Juan Pablo Fusi, Enrique Moradiellos, Carmen Calvo… (Uclés also mentioned the lack of parity: 27 men and only 6 women).

And, second, because, in his opinion, appearing on that poster under the motto “the war we all lost” gave the impression that he shared the motto as nodding. As Arturo Pérez-Reverte explains to this newspaper, the fact that this phrase appears on the poster as a statement, and not as a question, is due to a “layout error” due to which the question marks were not included. And so it is replicated everywhere. Is all the controversy due to a typographical error?

For Uclés, in any case, we did not lose the war all. “I think the correct title would have been the war that we suffer all, which is what I defend in my book, where I deal with the intra-history of the conflict. But we didn’t all lose it. There is a very important nuance: the war was won by the same people who provoked it, and they profited from it for 40 years,” the writer told this newspaper. The resignation of Uclés dragged others, such as that of the coordinator of Izquierda Unida, Antonio Maíllo, the deputy secretary general of the PSOE of Andalusia, María Márquez, the writer Paco Cerdá and the sociologist Zira Box.

“We already know that there was a winning side and a losing side, that’s obvious,” says Pérez-Reverte. “What we want to say is that all of Spain lost in issues such as women’s participation, years of the Republic, years of agrarian reform, years of the Constitution were lost… In short: Spain as a country lost years of progress.” The creator of Captain Alatriste is also surprised by these resignations, after 11 editions bringing together people of diverse ideologies, sometimes completely opposed. “There was even Cayetana Álvarez de Toledo with Juan Carlos Monedero!” he says. “I don’t want to talk about the kid (in reference to Uclés), but I think that if a character is being built, it shouldn’t be done at the expense of something so respectable.”

The debate that has been generated revolves around whether or not these types of events of a reconciliatory nature suffer from an unfair equidistance with respect to historical facts, whether they fall into revisionism around the war or whether people with progressive tendencies should go to them. And the issues related to the Civil War, generations later, continue to be difficult in Spanish society.

Since the Transition, a certain consensus was forged on the illegitimacy of Francoism, which for decades was reflected in the culture almost to the point of boredom—as the novelist Isaac Rosa ironically stated in his title. Another damn novel about the civil war!—, it was a shared truth, useful for closing wounds and building a common story. But it began to crack with the emergence of revisionist currents that responded to the growing attention on the crimes of Franco’s regime and placed the origin of the war in the 1934 revolution and the instability of the Second Republic. To the point that, on the recent fiftieth anniversary of the dictator’s death, the controversy remained open, while the extreme right gained ground among young men. This tension causes resentment when something sounds equidistance, even remotely.

To attend or not?

The journalist Edu Galán, in a column for the magazine Go titled How to fight by fleeing, enters into the matter: “We didn’t all lose (the war), the defenders of democracy lost it to some murderous coup plotters. But precisely I go to this meeting – and to so many congresses to which I have gone in disagreement with their titles – for this reason: to qualify it, explain it or dismantle it alongside its organizers. Progress comes from these debates.”

For his part, Antonio Maíllo, coordinator of Izquierda Unida, thought it was useful to attend, despite not being a priori according to the approach, to “confront through words”, but, like Uclés, he is not comfortable with the promotional poster, in which he also perceives that the participants resemble undersigned. It seems, in his opinion, “that he supports the thesis of equidistance, which not only do I not share, but I fight because it is an attempt to revise the tragic and unequal reading of the Spanish Civil War,” he explained in the statement announcing his resignation. “Defending the word and the accompanying debates also requires sensitivity on the part of the organizers so as not to frivolize,” he added.

The historian Gutmaro Gómez Bravo will attend and sees this attendance as something that falls within the normality of his profession. “I don’t understand all the noise about this. I know that I’m going somewhere to debate with people who don’t think like me, but it’s my job. I’ll talk to historians who think that the war is caused by the failure of the Republic, I think it’s because of a coup d’état. But we historians have to attend and give professional arguments,” says Gómez Bravo, who, moreover, acknowledges that the design of the poster doesn’t seem “very lucky” to him.

“We believe that we have made a balanced and plural program,” says journalist Jesús Vigorra, coordinator of the series, “we screened four films, two from one side and two from the other. We want to take the debate to the streets.” The coordinator adds that, in addition, the design of the posters has been the same for all editions of Letras en Sevilla. In the case of Uclés, his event consisted of a talk with the Cervantes prize winner Luis Mateo Díez in the presence of a group of students. Other scheduled sessions explore the need to forget or remember, compare the violence in both rearguards or ask, paradoxically, if a dialogue is possible in Spanish society about the war. “It is clear that this dialogue is not yet possible. Marañón said that a civil war lasts 100 years, only 90 have passed, but it seems that this one is going to be eternal,” concludes Vigorra.