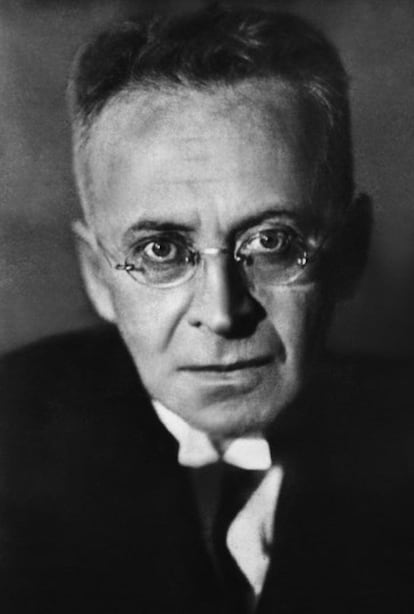

A torch burns, illuminates and leaves a trace. That’s what the writer Karl Kraus did with The torch (The Torch), the magazine that from 1899 until his death in 1936 he directed and practically wrote entirely from the heart of a Europe magnetized to barbarism. Some 30,000 pages of articles, essays, studies, poems, songs, plays, quotes, letters, aphorisms, satires and all kinds of literary genres that caused the scandal of the Austro-Hungarian bourgeoisie and the astonishment of contemporary writers such as Kafka, Brecht, Benjamin, Musil, Trakl, Schnitzler and — above all — Canetti.

It was there, in the pages of The Torchwhere a madness was born in the form of an anti-war plea entitled The last days of humanity. A mythical work that explains the horrors and cynicisms of war. A Babel of voices and genres that portrays the worst Europe. A too-unknown literary colossus that now, thirty years after its last edition in Spain, returns to bookstores with the Barcelona label H&O. And it does so in a terribly current context: where propaganda, lies and language seem the prelude to blind fanaticism and destruction.

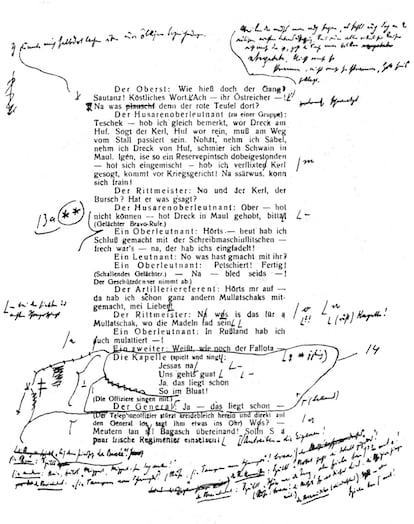

The best way to understand the spirit and texture of this work is to read the first lines of its author in the preliminary text. Kraus writes: “This drama, whose length would be equivalent to more or less ten evenings according to human measurement of time, has been devised for staging in a theater on the planet Mars. The public of this world would not be able to bear it. For it is blood of their blood, and the content is that of all these unreal, unthinkable years, ungraspable by a waking mind, inaccessible to memory and only preserved in some bloody dream; years in which characters from the operetta played the tragedy of humanity.”

With all this he was referring to the barbarity of the Great War. To the “disgust” that this idea of a homeland produced in him that leads the cattle for slaughter—the soldiers’ cannon fodder—to express, from the trucks, their enthusiasm for their own butchers. It is also – and perhaps above all – an attempt to denounce the “triple alliance of ink, technique and death” that is war.

Adan Kovacsics, prestigious translator and creator of this linguistic challenge, explains in the prologue that The last days of humanity It is “a work about and against power based on three axes: in the rear with its beneficiaries and profiteers, in power (political, economic, military) and in the victims (the common soldiers, children, the elderly, mothers, animals, the forest). For Kraus there is no power without victims; there are no great ones without little ones.”

For this reason, the author strives to offer an altarpiece with the aroma of a total novel that captures the spirit of his time. A choral story where passers-by, beggars, black marketeers, prostitutes, officers, soldiers, protesters, waiters, ministers, the imperial family, nationalist students, Galician refugees, war invalids, blind people, helpless poor, homeless children, literati, cafe journalists, correspondents on the front, a censor officer and a counterespionage agent, Polish legionaries, bohemians, dancers, singers, salesmen, speak. race programs, officials, parishioners, insane people and psychiatrists, members of the resuscitation service, people waiting in line at a grocery store and a woman fainted due to hunger, a military chaplain, repatriated mutilated people, prisoners of war, officers settled in the rear, civilians who have managed to avoid the military, revelers, motorists, the imperial music band, stockbrokers, salesmen, third parties, con men, swindlers and speculators, bourgeois and aristocrats, and even members of an association called “A laurel wreath for our heroes”.

They are only a small part of the enormous the person of the drama that parades through the 600 pages of this work full of humor, satire and biting criticism. Everything fits into a literary artifact filled with monologues and dialogues, with five acts and more than 200 scenes that attempt to compose, with small tiles, that oral history of his time that the vagabond Joe Gould would later pursue in another sense through the New York Village. Here Kraus seeks to capture the zeitgeist from when Peru of the Old Continent was screwed. Like Zweig and Roth, but in a badass version. Incendiary. Scourge. Intellectual whip.

For example, the denunciation of those who get rich from war. Glutton says, in verse: “Who wants peace? God save us from it! With how difficult it has been to adapt to war! We provide, we deliver and we are profitable; peace for us would be a disaster.” Golosa responds: “To each his own. To the hero, the dark pit. To us, the hyenas, to profit comfortably.”

The hyenas—speculators, rogues, beneficiaries and profiteers—are commanded by whoever holds the power of the ink. The patriotic gloss. The fanatical tares. The verse that glorifies her. The cruel language. The yellowish covers. The inflammatory headlines that newspaper vendors shout on street corners to pave the way for lies, propaganda, social blindness, destruction and mass suffering.

As Adan Kovacsics emphasizes, Kraus detected in language the genesis of the banality of evil—everything begins in the word, and Kraus makes it very clear—and pointed out the touchstone of collective delirium: when a man begins the experiment of living outside of guilt and, therefore, of being. Do not feel guilt; have no remorse. Stoke the Somme massacre. Opening the gas shower at Auschwitz.

This fresh from the Central Europe (Central Europe) of the 20th century invites a parade along the Ringstrasse Promenade, the Café Purcher or the Imperial Palace of Vienna. It is a journey through the Janov Pond, Grodno Market Square, the Baden-Vienna electric tram, its suburbs, a primary school, the Viennese newspaper offices, its cinemas and theaters and dance halls, the terrace of the Südbahn Hotel, the train stations, the little houses in Tyrol, the Gross-Salze spa, a Protestant church, a gynecological clinic in Weimar and a Berlin doctor’s office.

Furthermore, it is also a journey into the heart of the darkness of war through its battlefields, its craters, its clouds of smoke and horizons that look like walls of flames between corpses and the dying. There is no trace of epic, no heroism. It is also a provocative incursion into that other side of war that is money stained with blood, tears and corruption: a factory subject to the War Production law, the German front with its postal censorship, an Infantry regiment 300 steps from the enemy, a banquet of German and Bulgarian journalists, a military court in Kragujevac with its court martial, a military hospital with the howls of pain of the wounded, the Imperial Hotel where business advisors seek taking advantage of the war, or a party room at the headquarters of the High Command of the Austro-Hungarian Army among girls, drunks and officers. It makes you want to laugh, as Kraus warns in his prologue, if we were not forced to cry.

Eduardo Hurtado, editor of H&O, considers it “a small miracle” to have given birth to this project that aligns Karl Kraus, the translator Adan Kovacsics and the Nobel Prize winner Elfriede Jelinek and the writer Clemens J. Setz with respective epilogues. Hurtado is aware that Kraus’s colossus is a “demanding read.” But he insists there is a reward. “The work points out the coincidences between his time and ours: the political intrigues and corruption, the impudence of the press in the pay of partisan interests and its perversion of language, the growing tension between the popular classes and the hatred towards the foreigner or the different. It is not necessary to remember that Kraus writes just before the First World War and during the war. Hopefully – the editor sighs – this anti-war manifesto will sound the alarms, wake up consciences and recover sanity.” That’s what a torch is for.