Cristino de Vera (Tenerife, December 15, 1931) came to the surroundings of EL PAÍS, in Miguel Yuste, to eat apples with friends, at the time when the great Canarian artist fed on what the sky, God or painting told him. His lifelong love, Aurora Ciriza, rescued him for daily life, and that did enormous good for his survival as a human being and as a painter.

A great painter, a friend of painters and also a friend of the whole world, a student of Vásquez Díaz, in his youth he warmed his body, or cooled himself, before the canvases of El Greco in the Prado Museum. It was common to see him, in times of his great expansion in life, avoiding the traffic lights of Madrid, addressing passers-by with litanies that included questions about God or about happiness or about fear.

He asked people, in any circumstance, if they were happy, and if they were not, he also taught anyone with what he knew about God and men. He sang, or helped sing, amidst guitars that he considered part of his own voice, and thus he improvised verses that today would be used for the recitals in which Cristino de Vera, who died at the age of 94, converted friendship and the joy of the nights.

On those nights when I only ate apples, I called the friends I chose on the phone. Around midnight, that was his time. The purpose was to prevent those who he already knew would be awake from watching television. Their conversation at that hour, Cristino’s midnight, was vital and instructive: he wanted them all close to goodness and very far from the meanness that, for example, they were accustomed to watching: television.

When I met him, in Madrid, together with his friends Domingo Pérez Minik and Fernando Delgado, Cristino de Vera was preparing a large exhibition in Tenerife, always with his mystical, entire paintings, works that summoned the essence of his soul. Pérez Minik, important writer of the surrealist era, critic of Insula, one of his great friends, it was for him Sunday, just as almost all the others were called in diminutive. He stopped the world, and the ages, and his painting itself was his way of preventing death from coming. Until recent years, when he summoned her as if that endless lady was at the door.

“Dominguito, a whiskey?” he said to his old friend, that night I met him. Aurora, who was then his forever companion, made that evening in which Pérez Minik and the still young Cristino shared whiskey in milk cups. In Tenerife, where he went especially in the summers, to see his parents, to bathe, he walked along the street that led to the sea as if he were returning to the world in which his dreams resided. One day I asked Cristino what his metaphor for time was, because he was always looking for the essence of what escapes, life.

He told me: “They said that time was God’s ally, something of his silence, of the deep dark night with the stars shining. Looking at the stars you see that time is infinite. And all the silence of the starry skies is the echo of the infinite peace of the desert where so many seekers went to look for the echo, the voice, the explanation of how time can, with the help of all the mysteries of the earth, lead us to seek, to beg, the echo of the voice of the God of mercy. Always the mute harmony of silence, always the beauty of the things that surround us and purify our soul.” In an interview for this newspaper he told me when he turned 90, about the past in which he lived: “In Franco’s regime there was only pain without time.”

Tenerife was his place of return, always, and there he left in the hands of the Cristino de Vera Foundation, in La Laguna, in charge of Clara Cristina Armas de León, the greatest legacy of his work, open to other paintings that have made his inheritance as generous, and as open, as his own way of always offering the painting he made, so mystical, so related to God and the stars.

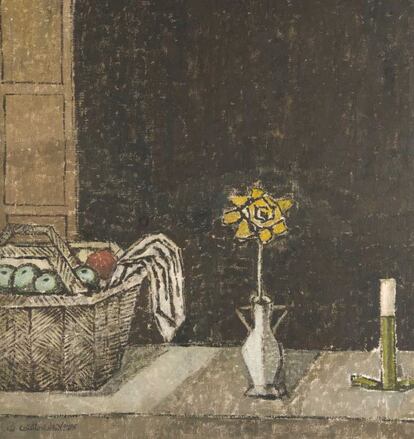

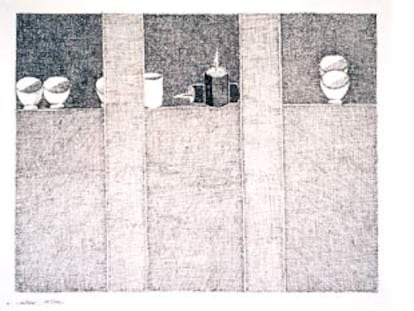

He was the heir of Zurbarán and Luis Fernández, Castilla, this country through which he walked like Quixote, was the strange continuation of the south of Tenerife, where he and his father (his great friend) found the essence of the island: the Red Mountain, which he shared, as if it were a painting, with his friend Dr. José Toledo.

Cristino never said anything that was not essential, close to the divine, and before the mountains and before the people he always spoke with the metaphor of a goodness that sometimes was of the guitar and sometimes was of love for God, whom he sought. He told me: “We would have to confront our poor and limited language with the divine calligraphy that turns everything into the silence of the greatest desert that is deep loneliness… I learned the beauty of Italy. It is the country that has accumulated the most beauty. I saw, therefore, the accumulated Italy. I attended to the silence that the spirit of man keeps, of the religions that tell about the divine, the energy of time… I always maintained some faith, sometimes it went out, but I have always had a relationship with the divine.”

Juan Manuel Bonet, one of his great friends, said of him that he was “a hermit of painting.” His life was, Cristino said, a long interior journey: “I have gone after all those mysteries that can restore faith. People think that religion is for children to make their first communion, and they do not delve into that light that sometimes comes to you in the morning and is a divine message wrapped in a white light.”

A mystic of infinite faith in painting, he never stopped being the man who ate apples and looked for God on the roads of Castile and his land and drank whiskey from cups of milk.