Is Beethoven’s music in danger? It is the fear that Norman Lebrecht (London, 76 years old) expresses in the epilogue of his 2023 book Why Beethoven? A phenomenon in a hundred workswhich Alianza Música has just published in Spanish: “It has been requested that Beethoven be banned for being a man and white, that he be silenced to make room for repressed voices.” He continues with a less-than-encouraging prediction: “It won’t be long before some tenure-seeking academic with a cousin in public relations presents evidence that Beethoven had shares in a slave-trading company, made teenage singers of his Ninth Symphony was kissed on the mouth, he insulted minorities and exposed himself in a public place.” And he finishes it off by leaving the reader frankly worried: “In reality, all of these statements are true, except one, as demonstrated by the book you have just read. In the current situation, the banning of Beethoven is as close as the appearance of a headline woke in The New York Times”.

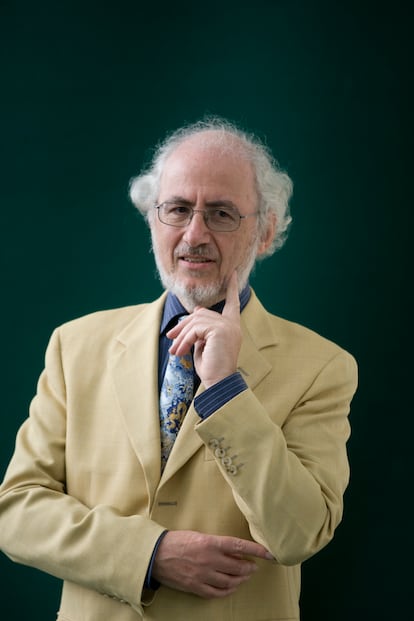

All of this comes from one of the most influential voices in English-language classical music criticism. Lebrecht is the owner of Slipped Discthe most influential classical news portal, and author of several provocative books, such as The myth of the teacher (Accent, 1997) and Who killed classical music? (Acento, 1998), where he questions the cult of the figure of the conductor and reveals the commercial intricacies of classical music. He is also an entertaining essayist and even a successful novelist, with his book Genius and anxiety: How the Jews changed the world1847-1947 (Alianza, 2022) and its best-seller titled The song of forgotten names which was adapted to the big screen in 2019. His intense activity in the media has combined journalistic columnism (of The Daily Telegraph to the magazine The Critic) with radio programs (on BBC Radio 3) and, in Spain, he has been writing for almost 30 years in the magazine Scherzo.

Lebrecht is, above all, a “sloppy but entertaining muckraker “British”, according to the accurate description of the American musicologist Richard Taruskin. A brilliant “garbage remover” that has combined an attractive narrative vein with frequent inaccuracies and a natural inclination towards sensationalism. His editorial excesses forced his monograph to be withdrawn from bookstores. Maestros, Masterpieces and Madness in 2007, following a defamation complaint by Klaus Heymann, founder of the Naxos record label. And his hatred towards the academicism that musicology represents has not stopped growing, as he demonstrated this month, in his column in The Criticwhere he calls the late Taruskin a “braggart” for questioning the veracity of Shostakovich’s memoirs published by Solomon Volkov in 1979, a book completely discredited for decades by most specialists and not a few critics.

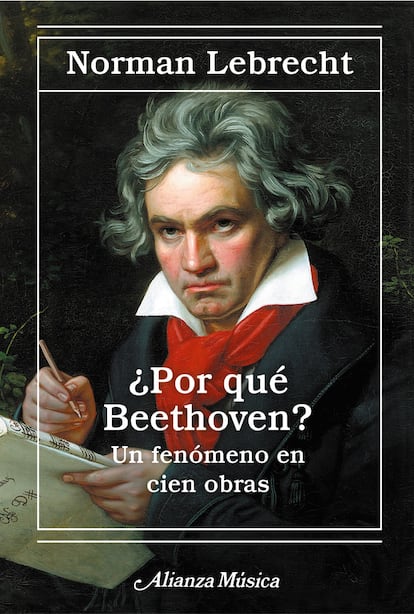

This new monograph by Lebrecht on Beethoven is a kind of second part of Why Mahler? How one man and ten symphonies changed the world (Alliance, 2011). If in the previous book I reviewed the impressive fortune of Mahler’s music in contrast to the indifference he garnered in his time, now he proceeds in the opposite direction with the unique case of Beethoven, a composer whose perennial success has not declined from his time to our own. days. However, he claims without any evidence that everything is going to change because of a musicology that listens to the social movements of Me Too and Black Lives Matter. It is worth clarifying that no musicologist has proposed “canceling” Beethoven, but rather addressing the lack of diversity in classical music and the need to expand the programming with works by marginalized composers. Overcoming this conservatism with a more diverse and inclusive repertoire has allowed, for example, the rebirth of the African-American composer Florence Price. But this is negative for Lebrecht: “The United States National Symphony Orchestra can only perform a Beethoven cycle along with the works of two African-American composers, George Walker and William Grant Still, neither of whom would boast of being on its level,” he states in reference to the concert cycle Beethoven & American Masters de la NSO de Washington.

If Lebrecht had read Taruskin, instead of insulting him, he would have understood the true reason for the survival of Beethoven’s music, something that he does not clarify in the 400 pages of his book. In the second volume of his monumental Oxford History of Western Musicthe American musicologist explains that Beethoven’s music inaugurated the musical world we live in today. His compositions changed the pleasant for the grandiose as an artistic purpose, which gave them a sacred aspect with immense future repercussions. Great musical works, like great paintings, began to be exhibited in public spaces specially designed for this purpose. Thus, concert halls were born as museums or “temples of art” where the public does not come to be entertained but to elevate themselves. And the sound exegesis of these sacred texts has shaped, over time, a series of great interpretations that we have treasured since the beginning of the 20th century thanks to recordings. After Beethoven, practices so common until then in classical music such as improvisation (today related to jazz) disappeared, and classical performers became the great “readers” of written scores that they continue to be today.

This is precisely what the book is dedicated to: the author selects a hundred of these compositions or “sacred texts” by Beethoven, comments on their particularities and highlights the recordings that he likes the most. The selection is not chronological and is grouped by themes (Beethoven in love, Beethoven locked up, Beethoven in trouble…). This structure allows the author a pleasant succession of biographical comments on the composer, anecdotes about his performers along with personal experiences of Lebrecht himself. It begins in 1798 with the SPathetic onata to comment on the patronage that allowed Beethoven to dedicate himself to composing and culminates with the Three equals (1812) that were played at his funeral. But Lebrecht peppers each story with lurid and sensational aspects such as the peculiar sexual habits of Prince Lichnowsky or the rudimentary catheterization that Dr. Wawruch performed on him in his last months. This obsession leads him to strange contradictions, such as stating that Beethoven never had sexual relations and, shortly after, raising the hypothesis that he had a secret daughter with the Countess Josephine Brunsvik, whom he also makes his “immortal Beloved.”

Leaving aside all the biographical considerations of Beethoven, woven with more or less imagination and sometimes contrasted with Wikipedia, the most interesting comments in the book deal with the performers. Lebrecht has known many of the great Beethovenian conductors and instrumentalists of the last 40 years. His first-hand portraits of directors such as the “holy madman” Klaus Tennstedt and the “peacemaker” Neville Marriner are very attractive. In fact, investigate that seventh symphony It is the Beethoven work most programmed by large orchestras and asks conductors such as Iván Fischer, Simon Rattle, Riccardo Chailly, Franz Welser-Möst, Leonard Slatkin and Fabio Luisi for this reason. He also consults their favorite recordings, as he does in the Violin Concerto with Gidon Kremer, and ended up opting for the wonderful live recording by Ginette Neveu, in September 1949, a month before she died in a plane crash at the age of thirty. There are many interesting recommendations and comments on Beethoven recordings, among which Alicia de Larrocha and the Casals Quartet stand out as the only Spanish performances.

The most personal (and sincere) part of the book focuses on the Pastoral Symphony. Here the author narrates the terrible relationship with his stepmother, which led him to instinctively hate that composition and the Bruno Walter album that he played at home. But Lebrecht devotes special interest to two famous Beethovenian speculative themes with unequal success. On the one hand, it continues to maintain the bizarre story of the composer’s Spanish family roots, something that was denied in EL PAÍS three years ago, after the dissemination of the baptismal record of his paternal grandmother who was born in Châtelet, a Belgian municipality near the city of Charleroi. And, on the other, the dedication of the very famous bagatelle For Elisewhich the author turns into an episode of “theft, fraud, sex, Nazis, intentional deception and corruption.” In this case, Lebrecht provides a new and very complex theory, with the help of Michael Lorenz of the University of Vienna, where he attributes the title of the work to a forgery to grant posterity to Elise Schachner, the granddaughter of the owner of the missing autograph of the work. But it does not take into consideration the latest contribution by Klaus Martin Kopitz, published in 2020 in The Musical Timeswhere he keeps alive the hypothesis that the work was dedicated to the singer Elisabeth Röckel.

In short, Beethoven remains practically synonymous with what we call “classical music” today, making it impossible to cancel it. In fact, James Mitchell’s article in Varsity, an independent publication from the University of Cambridge, in December 2020, which Lebrecht does not cite in this book, but on which he supports all his unfounded fears. Long live Beethoven’s music, but hopefully within an increasingly diverse and inclusive repertoire.