“In the beginning it was the virgin land of Africa. There were other dark-skinned men and women there, human beings who lived in a semi-wild state, slaves to the limits of nature. Everything was primitive at the beginning and even almost bestial (…) Spain arrived with many and on many occasions, and the dark-skinned men began to learn. These are the first minutes of the short documentary The miraculous sowing (1956), with the voice in off of Santos Núñez, one of the four members of the Hermic Films production company who sailed 21 days to film in Equatorial Guinea at the end of 1944. It was the first of several expeditions that extended until the sixties, commissioned by the Franco regime to spread the colonial activity that it carried out in African lands. Much of this production has been digitized for the first time and can be seen until June 6 at the Doré cinema in Madrid, one of the headquarters of the Spanish Film Archive, as part of the seminar Colonial film and documentary archives: the collections of Hermic Films which is held at the Carlos III University.

“Franco had from the beginning, since the creation of No-Do, the confidence and security that cinema is a wonderful propaganda tool,” says Miguel Fernández, director of the doctorate in Media Research at Carlos III and head Of the investigation Institutional documentary and colonial amateur cinema: analysis and uses. A project in which he embarked together with the Filmoteca, since the institution announced in November 2022 the donation, by the descendants of Manuel Hernández Sanjuán (director of the audiovisual pieces and head of Hermic Films), of more than 60 documentaries – many shorts and some long ones – filmed in the Spanish protectorates of Morocco, the Spanish Sahara and Equatorial Guinea. Although there have been other attempts to record Hispanic colonial activity since the late 1920s—such as the archives of the Ministry of Defense or the Air Force—this is the most “large and well-known,” according to Fernández.

“It is a source on history or, rather, on the way of presenting colonial history. It does not represent the reality of the colonies, but has been designed to raise a propaganda discourse of Spain’s tasks in those places. It gives us visual access to those areas, but it cannot be understood without that filter at the service of the General Directorate of Morocco and Colonies, which paid for the production.” The films combine images of a traveler amazed by his first contact with a world he has never seen before – the endless green of the Guinean jungle that does not fit on the plane, the camels that become miniature in the horizonless desert of the Sahara – with a sobering voice narrator who points out the benefits of exploiting the wood, coffee, minerals of Khouribga, or the literacy process and the installation of medical centers in the area.

“We want to think about these archives from the present. It is a part of the history of Spain, whether we like it or not, that is not taught in schools, and that helps us investigate the relationships we have with other geographies, reflect on migrations.” Fernández is aware of the muddy and complex path that talking about the issue has become with the new currents of decolonization; He mentions that he “had a disagreement” when trying to show the films in Guinea. “It is up to me as a researcher to understand the modes of production, the backgrounds, how they were filmed, contextualize and catalog the archive, and it will be up to other teachers, artists and specialists to debate them.”

The thesis of Western and Catholic culture as the superior is supported more by the different films filmed in Guinea. In one of them, the feature film imperial heritage (1951), some Ndowe indigenous people are seen building a hut with bamboo trunks and rope; In the following scene the headquarters of the Spanish government appears in the capital Bata, with the radio voice of Núñez: “Next to this primitive and simple life, another develops that Spain promotes, leading Guinea along the path of prosperity” . “When the Guinean territory is approached, we see a more paternalistic discourse, very much in line with Ramiro de Maeztu’s theory of Hispanicity, a discourse that infantilizes the people of these territories,” says Filmoteca technician Mabel Fuentes. , who, from February 2022 until this May, was part of the team that digitized a selection of the films from the donated collection, “which was not in a good state of conservation and that is why the scratches and lesions are noticeable in the emulsion.”

The archive’s conception of Morocco, to which this Wednesday’s session is dedicated, is much more dignified than that of Guinea. The approach is more ethnographic and is almost limited to describing the uses and customs (clay craftsmen, baking pita bread, weaving), and when evaluations are made, they are usually positive: “Essaouira, a beautiful city, there is no city Muslim like her.” “If the Guineans were treated as savages, with Morocco there is a familiarity due to Franco’s Africanist past, which is why he seeks a brotherhood or fraternity,” says Fernández.

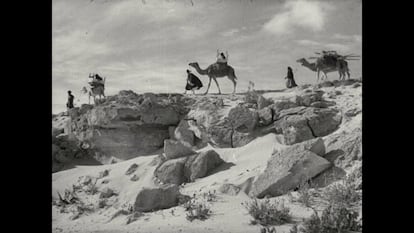

If the view of Guinea is one of pity and that of Morocco of brotherhood, that of the Sahara is exotic and is where the most impressive postcards are captured by the leader of Hermic, Hernández Sanjuán, who would become a reference in the cinematography of Spanish cinema made in Guinea. James (1950) is a contemplation of how a caravan of Sahrawi nomads set up tents in the middle of the desert, exploit any benefit that the camel can give them, set up a stone altar that faces Mecca and recites their prayers. “There is no rush where the immensity puts no limits on things or time,” says Núñez’s voice. A reverberation of the amazement that chroniclers tell about the first impressions of the conquerors in America: “Objects never before seen, not even dreamed of.” “One of the predominant notes is that of the romantic traveler who goes to these territories and becomes fascinated with some issues, and that serves to reaffirm his vision of dominance,” says the Carlos III professor.

There is another element in the archive that threads and connects a large part of the productions: the appearance of the Catholic Monarchs. With supporting images from their marble tombs in Granada or in the pictorial portraits of the time, they are the voice of the superiors to whom Franco and the regime respond. Embarking on a prophetic mission, they recover “the last will” of Isabel the Catholic: “I command my successors not to give up in the conquest”; or Núñez’s voice reappears with Guinean children celebrating mass: “This is how the will of Isabel the Catholic is fulfilled: that those who live in the new lands be taught our Catholic faith, that they be instructed in our good customs and that they do not receive any injury to their persons.” “They are quotes that were about 400 years old at that time. The movie (The miraculous sowing), like so many others, works as a brutal device of transformation and patriotic discourse,” Fernández insists.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_