In 1946, just a decade after the murder of Federico García Lorca, his friend Luis Rosales, who hid him in his house the last days of his life, wrote a play he never published. For almost eighty years she remained hidden, until now that the professor at the University of Barcelona Noemí Montetes-Mairaral has found her by chance in the National Historical Archive. The manuscript, in addition to the signing of the Granada, also carries that of Alfonso Moreno, but as the teacher explains “it can be undoubtedly affirmed that the vast majority of the ideas that pull the work come from Rosales.” Is titled ¿Because?and not only expands the poet’s known work, but adds a disturbing element to a story crossed by contradictions and silence: the relationship of the rosets with the death of Lorca, one of the deepest and most persistent wounds in the recent history of Spain.

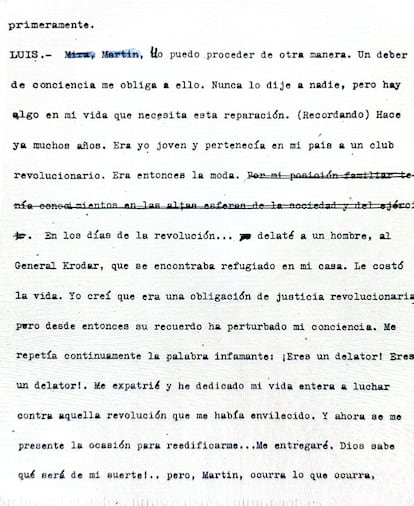

In a plot passage, a character, named Luis and that Rosales himself gives biographical features unequivocally related to him – a man of a bourgeois family with connections in the high spheres -, says these demolishing words: “… I can not proceed otherwise. A duty of conscience forces me. I young people belonged to a revolutionary club in my country.

The text, included in scene III of the first act, is so explicit that, knowing that Lorca was arrested at the home of the Rosales in August 1936, shortly before his murder, it is impossible not to relate it directly with it. In addition to the clear self -reference, which Rosales used to practice in his work, the name of the reported person, Krodar, also does not seem casual, with the same vowels as Lorca and two coincident consonants. “This is a bombing. Of course, you find this and you are cold,” says Montetes-Mairaral, who found the text while diving in documents to write an article about Dionisio Ridruejo. But without letting the tension rise too much, he soon calls for calm: “Anyone could understand that Rosales, in that fragment, is betraying, but it is impossible, you have to understand this well, you have to know the author a lot and have gotten into his skin to understand why he wrote such a thing.”

Let’s try that. As the teacher explains, the fragment does not imply a real delation by Luis Rosales – a idea that historiography has denied so far – but reveals the tormented mood of the poet, consumed because of the fault of having survived. Montetes-Mairal rules out real incrimination because “all evidence, all evidence deny it.” All versions accepted by experts agree that Rosales did not betray Lorca. What is also documented, explains Montetes-Mairal, is that it was due to a council of the Rosales family, with Luis probably as the head of the decision, so Lorca ended up refugee at home, the option also preferred by the poet himself, which had some additional alternative-such as staying in Manuel de Falla’s house. The Rosales had already protected other people linked to the Republic before Lorca, assuming a risk that at that time could imply a “death sentence.”

Rosales officially accepted history – which is still evasive -, far from harming him, favors him. He and his brothers Miguel and José, the teacher defends, were the ones who defended the most and tried to save the poet. Of the five Rosales Male brothers, only Antonio and José were “old shirts” of Falange – José, in fact, was the most important Falangist of the five – while Luis and Gerardo, the artists, were the least politicized. Miguel, Luis and José went to the Civil Government of Granada after the arrest of Lorca, desperately trying to release him. They did not succeed. José Rosales even dared to love Commander José Valdés, demanding an explanation. Luis Rosales, on the other hand, was the subject of a judicial process. As indicated by “the numerous scholars who have investigated the dark circumstances that wrapped the death of the poet”, the writer had to prepare a sheet of discharge to save not only his own life, but also safeguard those of the members of his family. After his process, instead of killing or imprisoning him, Luis was sentenced to pay a very high fine that ended up paying his father, Miguel Rosales Vallecillos.

Why then Luis Rosales writes a work in which he seems to be incriminated when he was actually close to running the same fate as his friend? Can this change the recognized version of the facts? “Let’s think that Luis Rosales wrote that text, and never wanted to destroy it. If it were really guilty, I would never have written it. If there had been nothing to do with his death, either,” Montetes-Mairal replies. The work is only “the evidence of the tireless woodwood of guilt, which then was rooted and would always root him, despite his undeniable innocence, because he was alive, while Lorca had died. It is the fault of the survivor, who believes he should have done more. And he is punished tirelessly for it.”

The thesis is shared by historian Ian Gibson, who finds in the text “an important discovery.” Few voices like his, fundamental biographer of Federico García Lorca, have so much authority in regard to the life of the poet. Gibson met Rosales well and always had a hope: “I always blamed him or said: ‘Luis, I hope you have written your version of the facts, of your fist and lyrics, and that you have not only limited yourself to talking with foreign reds like me,” he confesses. The appearance of this work, therefore, is presented as the possible response to that constant invitation to the poet to leave his personal testimony for posterity. Although the Hispanist has not yet had access to the full text of the work, the description of the key passage is unequivocal: “The allusion is obvious, right?” But he thinks the same as Montetes-Mairaral and points out, as he has been doing for years, Ramón Ruiz Alonso-who denounced Lorca-as the true “bad” in history. Rosales exempts him from direct responsibility. “In addition, it should be remembered that it was Lorca who asked for asylum,” he says.

The question of the delation of the poet’s whereabouts has been subject to study for years. It has been argued that he could be his brother Antonio Rosales, or even the oldest, Miguel, both contrary to the decision to house Lorca, something that the family has denied. The most widespread thesis, however, is that who betrayed the poet’s whereabouts was his own sister, Concha García Lorca, when on August 15 a violent squad was presented at the San Vicente garden to stop the poet and, not giving him, he decided to take his father. Ultimately, Montetes-Mairal emphasizes, “the one who was Antonio, Miguel, Concha-or who knows-, in reality, it doesn’t matter as much as the central fact that gives rise to the writing of that surprising paragraph in which its author seems incriminated: that Luis Rosales believed he had not done enough to avoid the delation, to avoid arrest, to avoid the death of his friend.” Lorca’s death, as Rosales said on more than one occasion, was the most decisive event of his life. That is why Montetes-Mairaral, when he read the work, was “completely overwhelmed”, as did the poet’s own son, Luis Rosales, when she was released. Rosales has preferred not to comment on this newspaper.

Gibson delves into the context of that Granada of July 1936. Lorca, already threatened and desperate, sought refuge in the house of the Rosales, an influential but divided family. “Having Federico at home was a risk,” he explains, remembering how some brothers, such as Antonio, an “exacerbated fan” of La Falange, did not want Lorca there. The family house, in addition, was dangerously close to the civil government, where repression was organized. When they discover it, Ruiz Alonso, then rival rival in La Falange, takes the opportunity to “crush” their political rivals and accuse the roses of protecting a “red”. “It was a fatality, it is like a Greek tragedy,” says Gibson, who has carefully documented how Luis Rosales and his brothers played life trying to save the poet.

Beyond the surprising passage explicitly dedicated to Lorca, Rosales’s work offers scathing criticism of authoritarianisms in 1946, in the heart of the Franco dictatorship. “It is impossible for them to have published it in those years,” says Noemí Montetes-Mairaral, remembering that the theater was the most censored genre then, well above poetry, “that it was very minority,” was the least monitored. It also highlights that the text, dated in 1946, precedes the famous in many ways in many ways 1984, by George Orwell, also rising as a premonition and a criticism of totalitarianisms that ravaged Europe. The work had only a private reading among colleagues from Escorial magazine and never saw the light. Until today.