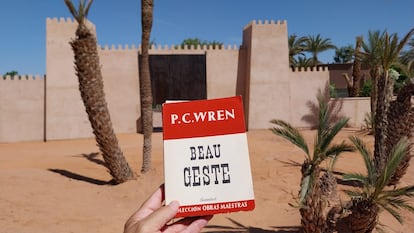

I couldn’t believe my eyes: there rose before my eyes, with its towers, its gate to the desert, its parapet and its battlements, Fort Zinderneuf itself, the legendary place where the climactic events of Nice GesturePC Wren’s great adventure novel about the French Foreign Legion, the most romanticized military unit in history, which enlisted writers such as Ernst Jünger, Jean Genet, Blaise Cendrars and Arthur Koestler, without forgetting Cole Porter, who I had to whistle the anthem, The pudding, like nobody. Was it a hallucination produced by the heat, the sun, the cafard, something I had eaten or the long hours of Formentor Literary Conversations sessions, especially the intense discussion on cultural supplements? I rubbed my eyes hoping to get rid of the mirage, but the strong one was still there, stubborn. The thing was even more amazing because I was there, at the Barceló Palmeraie Hotel in Marrakech, venue of the talks this year, to talk, precisely about Nice Gesture (1924), on the occasion of the centenary of the publication of the book and in the framework of the talks at the meeting dedicated generically to Geniuses, nomads and Bedouins (my contribution was in the “wandering” section, which is undoubtedly a good conceptual space to talk about Foreign Legionthe boot-busting unit of the “walk or die”, “march or die”).

Had the organization had the detail of bringing me the fort – which according to the novel is located very far away in the Sahara, “far, very far, north of Zinder, which is already in the region of Air, in the north of Nigeria?” ”—in order to inspire me and create atmosphere? It was doubtful, because Basilio Baltasar had nothing to think about! So how had he found his way to a hotel in Marrakech Fort Zinderneuf? And more worrying: would there be Tuaregs besieging it? Would I have to enlist for five years as legionaryWas I in imminent danger? Was I in for a Viking funeral like Beau Geste?

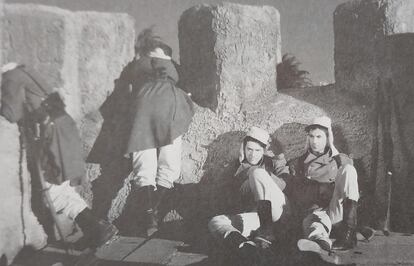

The disconcerting construction, which stood at the far end of the Barceló Palmeraie gardens, next to the Fitness gym, was exactly like the small fortress whose garrison, including the Geste brothers, had a hard time in the novel and in the films that have been filmed about it. I approached cautiously, as do the relief troops that arrive at the fort under the command of Major Henri de Beaujolais (only an Englishman could invent such a surname for a Frenchman), espahis officer and future Beau Sabreur from the Wren trilogy, completed with Beau Ideal. The wall did not offer a way to climb to the battlements and towers, but the door of the fort remained open (very recklessly, in my opinion). I looked out and there was the desert, indeed, with dunes and some scattered palm trees from which, I remembered, the Tuareg snipers could make lethal fire, who brushed off the garrison almost to the last man. Then a young man in sports clothes and with iPods ran by and stopped and asked me if I knew what time they closed the door. I wouldn’t have been more surprised to see Alice’s rabbit.

After thoroughly exploring the fort and being glad that the villainous Sergeant Major Lejaune (played on film as Markov and played in William Wellman’s canonical film with Gary Cooper) was not on guard, actor Brian Donlevy, married to the widow of Bela Lugosi, who is a point to play evil), I took some selfies and, more relaxed, I decided to investigate why a space-time fissure Fort Zinderneuf had slipped into the Formentor conversations. I knew that a fort had been built for Wellman’s film, but not in Morocco but in Buttercup Valley, near Yuma, Arizona. The hotel director, Monsieur Khalid Issig, somewhat disconcerted by my vehemence, could not explain to me why a replica of the fort stood on the perimeter of his establishment, although he linked it to the “desert experience” offered by the Barceló Palmeraie and which includes , after passing through the gate of the fort, access a little further to a Bedouin camp in a scenic oasis where you dine among camels, musicians and dancers (and an apparently stuffed stork), an experience that the participants in the conversations were able to enjoy. and that to the Tuareg of Nice Gesture They would have been surprised because the beautiful houris that appeared were more reminiscent of the Mama Chicho.

Monsieur Khalid, who apparently had not fallen for it, agreed that the fort was the same as the one in Nice Gesturea novel and films that he knew, although he did not know whose idea it was to replicate Zinderneuf. When I told him that I had seen a side door in the tower that no doubt allowed access to the top of the fort but that it was locked, and added that I would love to go and have the full legionary experience, he looked worried (“a to know what this guy is going to do up there,” he seemed to think) and told me that, unfortunately, the tower was empty and lacked an interior staircase. To my disappointment—I could have given the talk there, what an atmosphere!—he assured me that they would build a ladder so that the next time I went I could go up. I thought he meant it.

Armed with the unexpected experience of the fort, my Croix de Guerre and my passion for Nice gesture, and although I wasn’t wearing my pretty legionnaire’s kepi (which didn’t fit in my suitcase), my talk was a success. Especially because, in a display of opportunistic genius, I linked the (bad) luck of Zinderneuf’s legionnaires, whom the villainous sergeant arranges on the battlements of the fort as if they were alive as they fall, hit by the bullets of the Arabs, with jobs that are not replaced in the cultural journalism sector, as declining in social consideration, I noted, as the Foreign Legion. Going deeper into the comparison, I remembered the many casualties we had already suffered and, in the manner of a visionary dervish of the trade, I evoked all of us present as dead legionnaires clinging to their rifles and facing adversity with blind eyes on the parapets of Zinderneuf. If there had been stairs, I think he would have gotten us all to march to the fort, including the 2024 Formentor Prize winner, the writer Lászlo Krasznahorkai, who although he is Hungarian would not have mattered because that is what the Foreign Legion is for. We could have sacrificed ourselves by burning down the fort and given ourselves a Viking funeral as Digby Geste does with his brother Miguel (Beau) in the novel, but then we would not have enjoyed the subsequent buffet dinner. around the pool enlivened with guitars and which included oysters, a much better menu, it must be agreed, that the legionnaire soup o the pudding.

Mi Nice Gesture It was only a tiny part—and possibly the cultural lowest point—of the conversations and twenty very interesting conferences, each one on a related book. roughly with the desert, the Bedouins, the nomads or the djinnthe Arab geniuses. Among the best (in my opinion), Jordi Esteva’s talk about the book that the archaeologist and anthropologist Ahmed Fakhry wrote about the Siwa oasis; that of the Egyptologist Tito Vivas on Swimmers in the desert by Lászlo Almásy (despite the move that he took away my count), and that of David Castillo dedicated to The seven pillars of wisdom about Lawrence of Arabia (I cared less about Almásy because David talked about almost anything, including Cavafy and Kerouac, except about Colonel TE Lawrence; he did it brilliantly, though). Esteva recalled the time when, as a young boy, he found himself going to the hilt of majún, the Moroccan hashish jam, with Paul Bowles (whom Maria Belmonte would later describe as a “dandy nomad”). For his part, Vivas considered that with The English patient Almásy had been hit by “the curse of Hollywood” (anathema!), but we forgave him later when in a petit committee, with Luz and Pepe Massot, he told us about the time he was stung in Aswan by a very dangerous yellow scorpion and It got really bad…

But it was with Jordi Esteva, strong fellowwith whom I lived the other great adventure of Marrakech. If I managed to make a Sahara fort appear, he managed to lose (in addition to the suitcase on the return trip, and an old Goytisolian cinema in the Medina, the Eden, closed), a sorcerer. We were walking through Jemaa el Fna (I was enthusiastic about the cobras, some of whose secrets the man who manipulated them, Bodali, told me from colleague to colleague), when we found an individual sitting on the ground making amulets, the so-called grisgris. We asked him to make one for each of us and since Jordi speaks Arabic he was able to explain the entire process to us. He took pinches of different species and powders and introduced them with a propitiatory chant into a small bullet-shaped container. Then he rubbed this with a worn-out hoopoe carcass and closed it with tongs. Jordi asked him why the hoopoe and the magician reminded him that the bird—which served as a matchmaker between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba—appears in the Koran and is considered sacred. Their blood is used to write powerful incantations.

Very happy with our talismans, we became very popular by displaying them at the Conversations (more so than by quoting Adorno and Guy Debord, as others did), and everyone wanted one. But when we returned to the square the next day, with many orders, the sorcerer had evaporated. For me it was very sunny and the man would have other things to do. But Jordi became obsessed with the disappearance of the magicianas he called him, even more so when asking a one-eyed old man and a juice dispenser who seemed to him to be djinngeniuses, and they left him strangely overwhelmed. Finally, Jordi came to the conclusion that the witcher had never existed, despite the evidence of our grisgrises. “May Amun Zeus protect us and fill us with happiness, my friend“, he said, waving in the air the hand with which he portrayed the possessed panther woman in the Ivory Coast. And we got lost in the maze of the souk, like two veteran legionnaires in search of more adventures, disappearing in a burst of light, the aroma of spices, old readings and mystery.