During some of his best years as a photojournalist, while working for the Madrid section of EL PAÍS, Cristóbal Manuel (Almería, 63 years old) was portraying two cities at the same time. The first was that black and white Madrid of the neighborhoods of the nineties that appeared on the pages of the next day’s newspaper to accompany news of evictions, circus arrivals at Christmas, illegal nursing homes or robberies. The photograph was published, the news was forgotten and we started again. The second city was what he called “city of sadness” and he never forgot that.

To illustrate it, the photographer uses, in many cases, the same images that were published in EL PAÍS-Madrid from those years. But stripped of the story they told and the concrete reality that drove them; Now they talk about something different. Therefore, the crestfallen elephants of that 1992 circus that no one remembers are no longer just that. For this reason, the old woman in the residence who was crying because she was going to be evicted is now a symbol of something else. This paradox is one of the keys to the exhibition sadness city, which is displayed in the Patio de Santo Tomás de Villanueva, at the University of Alcalá de Henares, until December 15. “They are images of isolated beings who do not fit in, who do not find their place in a hostile city that was the one I found when I arrived from my paradise of Almería. sadness city It is not Madrid. Maybe it is a part of Madrid, but it could be any other city, or a part of any other city. Deep down, it is an imaginary city made over the years with real images,” explains the photographer.

Cristóbal Manuel studied at the Almería School of Arts. I wanted to be an illustrator, or cartoonist, or painter. At the age of 20 he worked painting billboards, and for that, he often used a photograph that he took himself and then reproduced on the billboard, helped by a grid. He then became interested in photography. The owner of the most prestigious commercial photography studio in the city, Emilio Túnez, specialized in weddings, baptisms and communions, seeing the young man’s good eye, signed him. Manuel began to earn money and busily walked around Almería with two Hasselblad cameras, paid for by the studio. One day, in a cafe, two great Almeria photographers, Carlos Pérez Siquier and Manuel Falces, noticed him, precisely because he was carrying those two cameras. And they called him.

“They taught me a type of photography that I fell in love with. And I gave up weddings and baptisms, despite the money. And then, I met a journalist, Antonio Torres, EL PAÍS correspondent in Almería, who asked me to accompany him to a report, and that day I realized that journalists went to places where no one went, and that allowed me to do photos that no one took, and I became a press photographer. But I never wanted to be a journalist,” he says. The photographer Martine Franck, wife of Henri Cartier Bresson (of whom Cristóbal Manuel was an admirer), both visiting Almería, gave him the last piece of advice: “Get out of here.” It was 1992. He headed for Madrid. and for Sadness city.

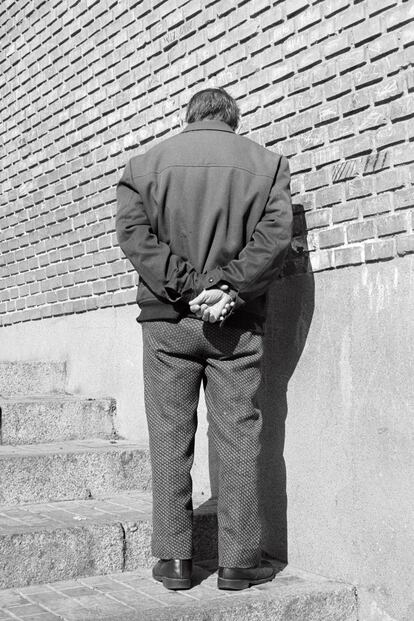

Shortly after arriving, he photographed a neighbor from his La Elipa neighborhood with his back turned, with his hands behind him, in the middle of a staircase, looking at an exposed brick wall. He is the number 1 inhabitant of his particular imaginary city, the photo that opens the exhibition. On another occasion, he photographed an elderly woman in a bathrobe dragging a shopping cart and a very poorly dressed man sitting in front of a Santander Bank branch, overwhelmed by something, looking at the ground. “This guy could be me because that was the bank in my neighborhood and maybe the man was like this because they didn’t lend him money, they didn’t lend it to me either.” The photo would later serve to illustrate some of the thousand economic crises that shook Spain in those years. With the journalist who signs this chronicle, at that time an apprentice reporter for the Madrid section of EL PAÍS, Cristóbal Manuel portrayed that old woman who was crying at dinner time in a very sad residence from which she was going to be evicted for leaving. You know what illegality.

Another time, to illustrate the overcrowding of commuter lines, he went to Atocha and photographed a platform at rush hour. He achieved the objective. But more than 30 years later, what stands out most about that photo is not exactly the crowd of people, but the stunned face of a twenty-year-old who looks at the camera, absorbs all the light from the station and seems to say: “What do I do?” here”. On a visit to the Soto del Real prison for another report, a couple of inmates asked him to take their photo because they had gotten married a month ago in prison and did not have a wedding portrait. The former photographer from Emilio Túnez’s studio thought about the twists and turns that life takes.

None of these images were ever on the front page of the newspaper. Cristóbal Manuel did not make them with that intention. Deep down, even then, all those snapshots were part of the same series and he sensed it: “I was very meticulous and when I took a photograph for the newspaper that I liked, I went to the archive, asked for the negative, developed it and kept And around those years I did a small exhibition in a bar in Lavapiés. The exhibition was already called Sadness City”.

In 2000 he joined the staff at EL PAÍS and was promoted to editor of the supplements. Temptations y The Traveler. He was a special envoy several times and became the newspaper’s chief photography editor, a position he abandoned when he left the newspaper in 2022. Before, he had won the 2011 Ortega y Gasset Prize for the image of a man walking naked through the streets. of Haiti a few days after the earthquake that devastated the country in 2010. But he never returned, except on very rare occasions, to run into the characters of the neighborhoods of Madrid, who at the same time were inhabitants of his sadness city. Partly because he no longer went there, partly because that world had ceased to exist.

The photographer now walks through the exhibition and looks at the photographs one by one: four old men absurdly go up and down an exercise ladder with a devastating expression of dejection and resignation, some ladies fan themselves while sitting on a bench in the sun, an employee of the Company Municipal Transport (EMT) on strike leans on the shoulder of his wife, who looks askance out of the corner of her eye towards the left…

Then he recalls the many years that have passed since he captured those images and proudly confesses: “These are the photos that I came to take when I left Almería.”