In a museum you don’t run, you don’t shout, you don’t sing and, of course, you don’t organize a costume parade or go camping. When faced with a baroque landscape or portrait, you don’t invent what happened in the painting or imagine who the bearded man in the painting could have been: what would he be thinking about while he was being portrayed, what would be his favorite food? Those things aren’t done, are they?

Who says it?

“I defend another way of entering museums,” explains Susana Gómez, Strategy Director of the Banco Santander Foundation. “If we bore children, if we expel childhood from the corridors of an exhibition hall, how are we going to generate a young audience?”

The wrong questions

The paradigm, Gómez says, has fortunately changed in the last decade and a half. Today’s museums give as much importance to the exhibition space as to their pedagogical projects, an evolution of which Gómez herself and the Banco Santander Foundation have been protagonists, almost pioneers. It all starts, he says, by asking yourself the appropriate questions, when standing in front of a work of art: “We don’t want children repeating what they might have learned by reading Wikipedia. We want to offer them an experience, make them feel that the museum also belongs to them.” Gómez especially emphasizes this point: involve them, invite them to feel and comment on what it evokes in them, to reflect out loud without complexes; to break the barrier that leaves them out.

They are the authors of the questions that encourage young audiences to jump over the fence that keeps them away from art: Estefanía Santiago (left) and Carlos Almela, from Hablar en Arte, the association that the Banco Santander Foundation has commissioned for some years these cultural mediation activities. They usually work with students from schools in vulnerable environments or with institutions dedicated to the care of people with physical or intellectual disabilities.

—Before going around the room, I wanted to ask you a few questions. Imagine: How many pigments can there be in all these paintings? How many people can have fallen in love in this room? (…) Among the olive trees and holm oaks outside, 20 species of birds live. Would you dare to imitate their songs for the next visitors?

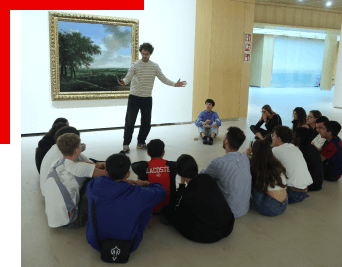

Carlos Almela and Estefanía Santiago get them to overcome their initial shyness, they record them chirping and whistling, and the group of students from the Ciudad de los Muchachos school in Madrid and the two teachers who accompany them start the activity with enthusiasm.

They have just paraded in costumes—“Didn’t Beyoncé do it at the Louvre? Come on, everyone cheer up!”—and the teenagers are now looking for which paintings evoke the most in them, to answer those appropriate questions that those from Speak in Art:

-This? Isn’t it very dark?

—But what do you see here?

—I don’t know, loneliness, a long sadness.

—Oh, girl! How intense you are.

This is how two of the students, teenagers in their final years of ESO, talk in front of an abstract work by José Manuel Broto from 1989. Are they wrong in what they observe?

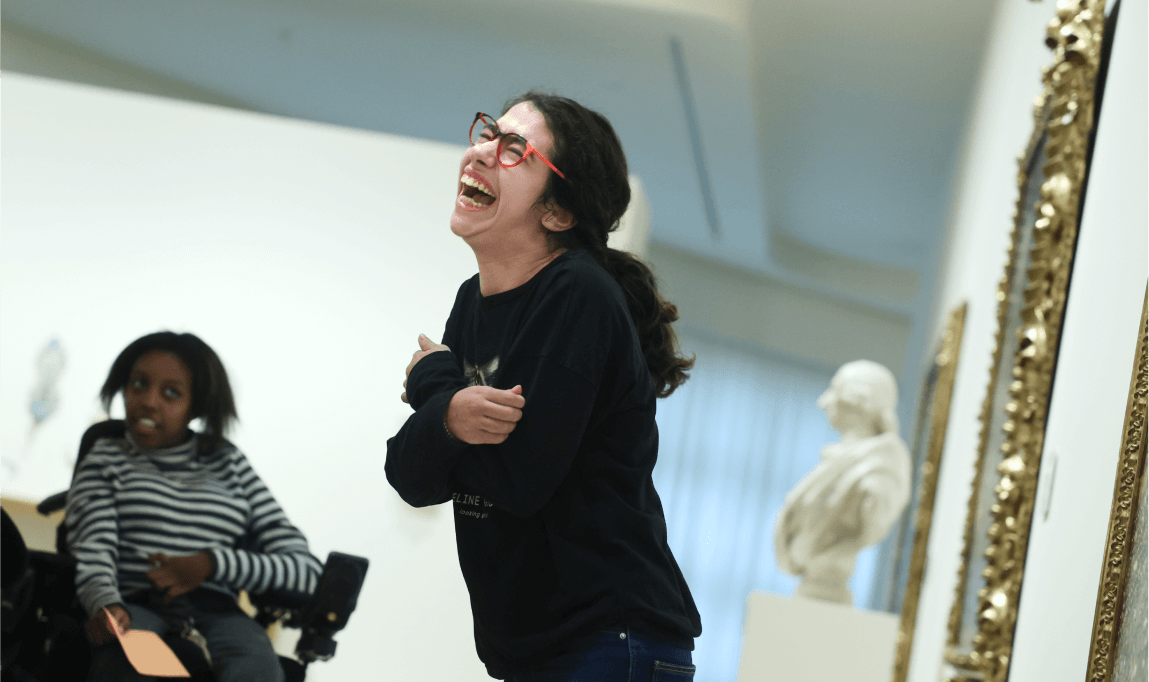

Then, each group stands before the chosen work and tells the rest. And here stories of all kinds emerge: some gracefully construct the most implausible plot of a Hollywood disaster film, others question themselves, leaving listeners astonished: “In a still life, why are fawns or birds only food?” chickens and not dogs or cats?” Indeed, it is a cultural characteristic. Art speaks about us, and we can dialogue with it.

Once the end of the activity has been declared, everyone runs to the exit, happy because they have escaped the classroom for a couple of hours, because for the first time they have not been scolded for speaking in a museum…

Two decades ago, artistic sponsorships basically consisted of paying for the production of an exhibition and then displaying, very large, the payer’s logo next to the vinyl with the artist’s name. This is how Gómez, who joined the Santander Foundation as an intern and who, after a few years dedicated to technological innovation, ended up leading to the path that seemed most favorable for her, remembers it with a frown. Gómez is also coordinator of the master’s degree in Cultural Management. from the Carlos III University of Madrid—, the intersection between art and pedagogy. “We wanted to leave a mark, more transcendent projects. And so we gradually proposed them to the institutions with which Banco Santander had an agreement.” This is how they arrived with that philosophy so well received in the institutions themselves to places such as the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid or the MACBA in Barcelona. And, in this second decade of the 21st century, all the entities that collaborated or received funding from Fundación Santander at some point were incorporating this vision, which is already a reality for the majority.

Gómez remembers and can cite dozens of projects conceived in this way, an endless string, but he stops at one that, in his opinion, exemplifies the ideal they championed. Yeast, it was called. For two months, the chosen artists lived with students from school classrooms to present the result of their plastic research to the viewer at the end of that period. And, to achieve this, they managed to mobilize public schools and municipal spaces in Madrid such as Matadero or CentroCentro. “It was a before and after. We always remember the professor who, to a certain extent, changed our lives. Can you imagine the impact of an activity like this? Thanks to the existence of the initiative, many boys and girls from vulnerable contexts had the opportunity to get closer to art and culture.”

Art speaks to all of us, if we know how to listen

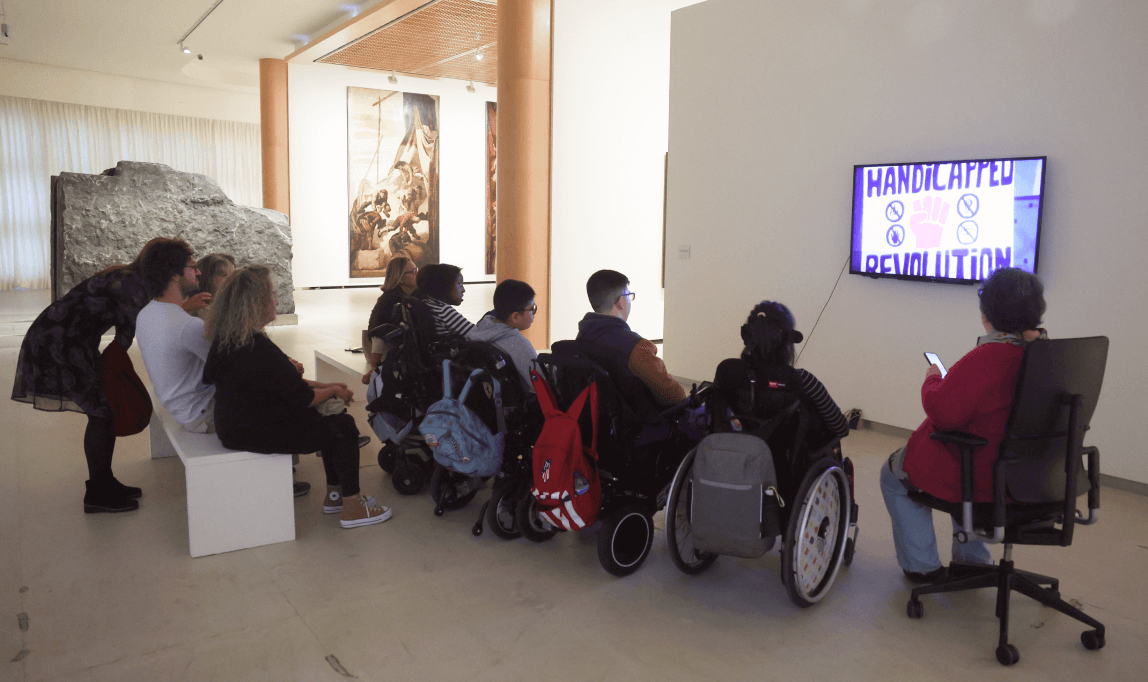

Costa Badía, artist, performer, curator and cultural mediator, introduces herself to the group of participants, all young people with cerebral palsy from the Bobath Foundation, and tells them what they are about to see projected: the documentary Crip Campabout a revolutionary camp in the seventies that opened the way to equality for people with disabilities in the United States. Badía has been fighting against these limits or impossibilities for years, working regularly with museums like the Reina Sofía and has even promoted a gallery in line that promotes the work of artists with disabilities: Tullida Gallery, he decided to call it.

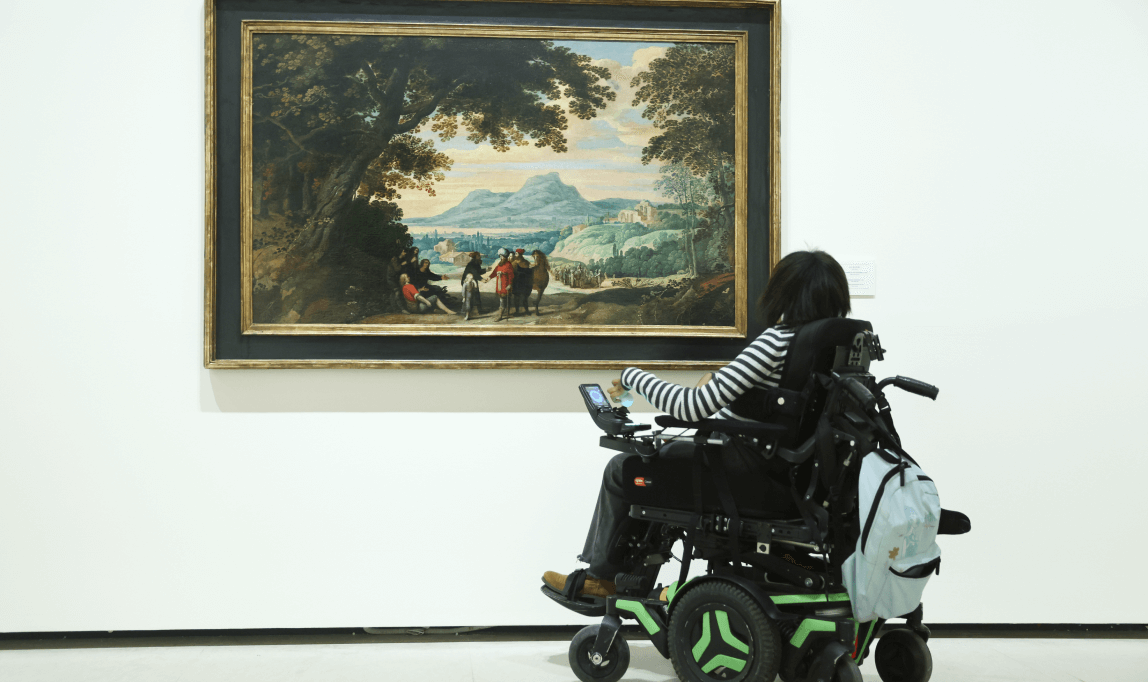

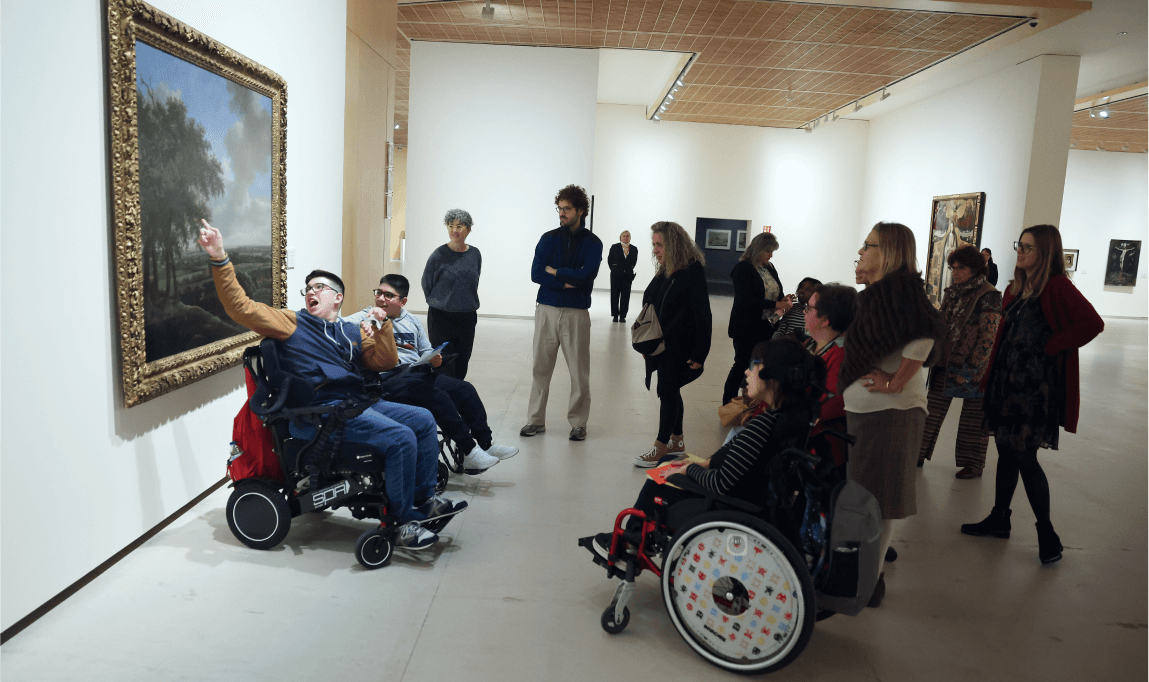

The plan is almost identical to the one that the schoolchildren developed a couple of days before: stand in front of the chosen painting and ask themselves the desired questions, as soon as they have finished watching the documentary. Caregivers and participants walk through the hallways: “Is this painting where you would like to see a sunset?”, “Is this where you would like to come and give you a kiss?”…

The 1,200 square meters of room are there for themselves, a feature that makes this Banco Santander space in Boadilla del Monte special. Gómez says that they are very lucky, because what they do would not be able to be carried out if at the end of the year someone quantified the number of visitors or measured the success of these programs in figures. “No one demands them because here we all know that there would be no way to do this with 6,000 or 10,000 students a year. That we manage to bring 400 people in these conditions means truly improving 400 lives without opportunities. We have had to learn to tell it, of course; what do we say? That art serves to put people we tend to push to the margins back into the center of society”.

All the groups have already told what paintings they have chosen and why, they have already been able to reveal their confessions and dreams to everyone. And, finally, Carlos Almela asks you one last thing.

—Do you see this tent that we have set up in this sculpture by Anish Kapoor? Like in the camp in the documentary. I want each one to come up and leave here a special object for them, that they would want to take to that camp no matter what.

One by one they approach, pass with the chair between the granite halves of the Indian artist’s sculpture and place their objects: little by little they pile up an Atleti shirt, a cameo, another pendant, a flashlight, photos of a pet…

A museum full of life, art that speaks to us and invites us to talk

Credits

Writing Alexander Martin

Editorial coordination: Juan Antonio Carbajo and Francis Pachá

Design coordination: Adolfo Domenech

Design: María José Durán

Development: Rodolfo Mata

Photograph: Jaime Villanueva