The story is told by László Krasznahorkai himself as if it were the sequence shot of an art house film. Béla Tarr knocked on the door of his house with the proposal to adapt satanic tango. The writer had a Homeric hangover, he had just woken up, it was mid-morning, a dark day in Budapest, the late 80s in communist Hungary. They didn’t know each other yet. He answered no. He even told him that he would never write again and closed the door. Béla Tarr walked with his hypnotic cadence around the building, noticed a window with the light on and rapped his knuckles on the glass. Krasznahorkai was washing his face in the bathroom. He opened it and looked at Béla Tarr’s face in the rain. “Watch my films and you will understand why I want to adapt your literature,” the filmmaker told him.

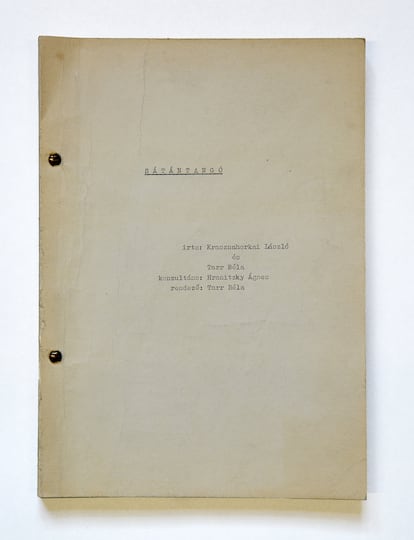

The Hungarian author told it last week to Bernhard Fetz, director of the Literary Archive of the Austrian National Library, during a reading at the Vienna Museum of Literature. Fetz remembers it in his office in the Hofburg Imperial Palace—the Habsburg residence for centuries—along with the original scripts of the films. Satanic y Werckmeister Harmoniesbased on the novel Melancholy of resistance. On the table there is also a giant minotaur head, a papier-mâché sculpture that Krasznahorkai used on occasion during the presentation of his novels. The Nobel Prize in Literature in 2025 decided last year that his literary heritage be preserved in the prestigious Viennese archive.

Krasznahorkai (Gyula, Hungary, 71 years old) often cites the influence of Austrian literature in his work. The weight of authors such as Robert Musil, Ingeborg Bachmann, Heimito von Doderer, Thomas Bernhard: all of them preserve their literary legacy in this archive. The Swedish Academy highlighted that “he is a great epic writer of the Central European tradition, which extends from Kafka to Thomas Bernhard, and is characterized by absurdity and grotesque excess.” Thomas Bernhard’s favorite café, the Bräunerhof, which closed this summer, is located on the parallel street. The tuberculosis sanatorium where Kafka died a century and a year ago is in Kierling, on the outskirts of Vienna. On this street it is literary even to the neighboring building, home of the Crypt of the Capuchins, where Joseph Roth served as an honor guard at the funeral of Emperor Franz Joseph I and cried. Roth and Krasznahorkai are literary antagonists, but both are gravediggers of their time.

The writer lives most of the year between Vienna and Trieste and keeps his house in Budapest, a triangle with a symbolic power typical of Austro-Hungarian geography. However, the reason for transferring his legacy from Budapest is also political: rejection and flight from the far-right regime of Viktor Orbán in his native country. “The political situation in Hungary is what it is, and many artists and writers are moving their artistic archives outside the country, such as the author Péter Nádas, who gave it to the Berlin Academy of Arts,” explains Fetz.

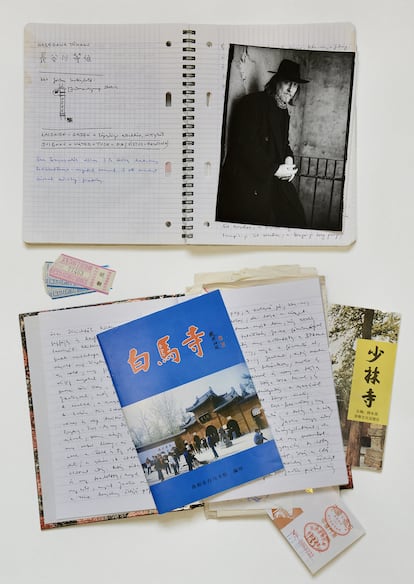

The treasure is enormous and is distributed throughout different rooms and corridors. They are still working on inventory. It includes all his manuscripts, unpublished texts, different versions of his film scripts, annotated drafts, proofs, diaries, research material, cover designs for his novels and stories, photographs, audio and video material and unique correspondence with more than 700 senders from 23 countries; more than two thousand letters since the 1980s. The legacy of an author translated into more than 30 languages—and yet considered cult; a difficult pleasure for a marginal audience.

The sound recordings of a night of partying in the kitchen of poet Allen Ginsberg’s New York apartment are preserved, in which David Byrne, singer of Talking Heads, can also be heard. Material proof that Thomas Pynchon exists is preserved: a typewritten letter by the American writer (“Hello, Lászlo!”), signed “Tom,” in which he congratulates him on the 2015 International Booker Prize and tells him that, between acts of futility, he managed to read Melancholy of resistance. “It reminded me why I started reading novels, it was like living for a while in a place I needed to be.”

Photos of his childhood in Gyula are preserved, of his music bands in Budapest, of his travels around the world. In the 90s, Krasznahorkai traveled for long periods through South America, Mongolia, China and Japan, boarding freighters crossing the Atlantic. In one of the black and white photos, he sports a dark coat, a felt hat, a beard, long hair, and the undeniable elegance of a bohemian musketeer.

The galleys with annotations of the novel are preserved Herd 07769not yet translated into Spanish, in which Krasznahorkai addresses the explosion of neo-Nazism in East Germany in a fictional town in Thuringia. He master of the apocalypse He writes the book in a single sentence of more than 400 pages. “It is easy to read compared to his early works,” says Bernhard Fetz. “As in all his texts, his humor is as deep as it is human. Johann Sebastian Bach is the real hero of Krasznahorkai, who plays the piano. And the neo-Nazi protagonist is a Bach addict.”

Part of the collection has been on display since June in the exhibition Again and again. The narrative universe of László Krasznahorkai from the Ferenczy Múzeumi Centrum in Szentendre, on the banks of the Danube, about twenty kilometers from Budapest. Krasznahorkai’s literary heritage is the second belonging to a living Nobel Prize winner in the archive of the Austrian National Library. The writer Peter Handke already bequeathed his before.