What are our favorite novel phrases? There are the classic ones, of course: “all happy families look alike”, “many years later, in front of the firing squad…”, “I detest vulgar heroes and moderate feelings”, “whatever comes we will go towards it smiling”, “God knows that we should never be ashamed of our tears, for they are the rain that falls on the blinding dust of the earth that hardens our hearts.” But I am referring to those more personal, personal phrases that have marked us in a special way as readers and make up the tenuous lines on which we effortlessly draw the calligraphy of what we are.

Each one will have their own. Among mine are “it is very difficult to fight against the desire of the heart; everything it wants to obtain is bought at the price of the soul” (Justine), “disappears from the world as if wrapped in a mysterious cloud, inscrutable in the depths of his heart, forgotten, without the forgiveness of those around him and excessively romantic” (Lord Jim), “you cannot live without loving” (under the volcano), “if the island was populated by spirits, they were not monsters but nymphs” (The magician) or “he recoiled from the fear of being a coward and not from the possibility of being hurt” (The four feathers). And for some time now there is another phrase that has joined these and does not stop echoing in my head: “a happy man has no past, an unhappy man has nothing else” (The narrow road to the deep north).

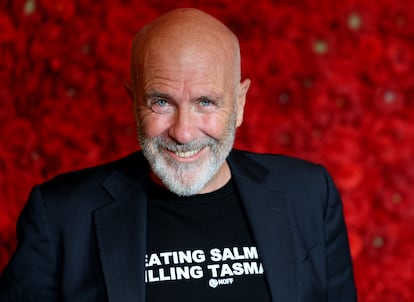

It is impossible to go to the authors of the previous sentences to comment on them, since all of them (Larry Durrell, Conrad, Malcom Lowry, John Fowles and AEW Mason) have already died. But in the case of the last one, by Richard Flanagan, yes. And I have done it.

I had the chance to speak with Flanagan about his latest book, Question 7 (Books of the Asteroid, 2025), a wonderful and at times disconcerting text that goes beyond genres—narrative, essay, memory—and that is ultimately a moving song to his family and his land (Tasmania) in which appear topics as apparently varied and connecting as the Second World War, the Japanese concentration camps, the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and how they were created, the love relationship between HG Wells and Rebeca West, Chekhov or the kayak accident in which the author almost drowned. Question 7 It has a lot to do, precisely, with my favorite Flanagan novel—and one of my favorites in general— The narrow road to the deep north (Penguin Random House, 2016), from which a very good five-part Australian miniseries was made in 2025 with the same title – taken from the Japanese poet of the Edo period Matsuo Basho -, broadcast on Amazon Prime and with Jacob Elordi, Ciarán Hinds and Odessa (!) Young. The plot is centered on Dorrigo Evans, a doctor from the small town of Cleveland, on the island of Tasmania (the same town where Flanagan was born), who falls prisoner of the Japanese and experiences the horror of the Death Railway and the camps, from which he emerges a war hero for his selflessness. The novel shows Evans as a young man, during the war (Elordi) and already mature and become a celebrity (Hinds) but tormented by the experience of internment and the cruelty of the guards and the memory of a great unhappy love (Young).

The phrase: in the novel it is said that “when he grew old, Dorrigo Evans would not be able to tell if he had read that phrase or had invented it himself.” I asked Flanagan point blank about the origin. He was surprised by my enthusiasm for one line in a 445-page book. He hesitated a little. Is it something that you can apply to yourself? I encouraged him, that it came from within you, come on. “Look, sometimes I think yes and other times that, well, that it was a pure invention, an idea that I had for that character. I am substantially happy and that character was unhappy because of a love from the past that tormented him. That phrase was true for him, who had a past from which he was never going to escape.” I told him that compared to the rapture of his novel or the emotional parts of The question7 He seemed very serene to me. River. “I am not a calm man, it is a mask.”

The narrow path It is a book full of poetry, Basho, Shisui, allusions to Ulises from Tennysson, to Catullus, to Kipling, the Celan quote at the beginning, the haikus of the Japanese officers when they are not cutting off heads, phrases like the underlined one. “I like poetry, but seeking to create a poetic effect in prose seems like a mistake to me. When novels work is when they cross borders, oceans, storms and waterfalls, and reach other cultures and languages, so they have to submit to the story and its mystery, it is the story you tell that matters and survives. I think it is dangerous to succumb to poetry, the novelist has to narrate.”

Flanagan also disagrees that The narrow path y Question 7 There are two ways to tell your father’s story. “Question 7 It is linked to several of my novels, such as the first, Death of a guide. And it is essentially a love letter to my parents and a tribute to a disappeared world, that of my island that is fading in these times that sweep away everything.” Isn’t Dorrigo Evans a alter ego from his father, then? “No, let’s see, there are many people who think this, you are not the first. My father, oh how my father was, the character in the novel is very famous, a surgeon and war hero, and a womanizer, imprisoned in the solitude of fame, while my father was a teacher, a family man, a houseman, without great achievements, he was with the people who loved him and those he loved. It is true that my father had those experiences in the war, the fields, but the challenge of the novel was precisely to escape the memories of my father and invent. Do you know what my father told me? That it had been lucky to be a prisoner because there you only had to suffer and you didn’t have to fulfill your role as a soldier, which was to inflict pain on others. My father’s idea of decency and love in those circumstances, the solidarity that helped them survive, was what helped me, with the alchemy of memory, to write. The narrow path”.

In Question 7Flanagan himself visits the field where his father once stood. Is there much left to exorcise of that, especially in Japan? “I see it differently, human beings survive because of their ability to forget, and it is understandable, although there is also the freedom to remember and delve into memory. If you bear witness to the darkness that closes the wound and brings some hope and light for everyone. But I do not seek reparation.” Flanagan reflects that the atomic bomb whose creation goes through Question 7 He made it possible for his father to survive the war and therefore for himself to exist. “We believe that we live in a rational and quantifiable world, but we are the fruit of strange stories and a strange chain of events.”

Going back to The narrow pathas unforgettable as the phrase that motivates these lines is the wonderful scene of falling in love in the Adelaide bookstore. “I have always found bookstores and libraries very erotic places.” The beautiful image of the girl with the red camellia in her hair… did it exist? “No, I’m afraid I made it up.”

While we were there I asked him if it’s weird being Tasmanian. “Tasmania influences me more than I thought, I am very marked by that primordial jungle, of ancient trees and wonderful animals, and by the indigenous culture and its conception of time and nature, so different. I belong to two worlds, the Western one and that of my island and I have understood that my task is to write about what I know, about what Orwell said was the most difficult: what you have in front of your nose.”

Curiously, I don’t know how we ended up talking about love. “Family is very important. But you must not waste any kind of love, you must honor everything that comes to you and extend it to what surrounds you. It is a word that we are made to believe is small and naive and we are encouraged to refuse it and not offer it as we should. But we must not lose any opportunity to love. Nor waste any form of love.”

I said goodbye to Flanagan with a bittersweet feeling. The conversation had had emotion and poetry, but not in the ways I expected. Tasmania, family, the bomb, kindness and dignity, rugby and possum hunters. You can’t reduce a writer to what you project onto him. It’s always something else, usually much more. What you see in his work and what moves you so much does not have to be what is relevant for the author. And yet, the girl with the red camellia… “A happy man has no past; an unhappy man has nothing else.”