One frigid, sunny morning last December, Indian novelist Kiran Desai’s living room seemed like the quietest place in New York. It has merit: it is on a street of low houses built in the 1930s in Jackson Heights (Queens), perhaps the most bustling area of the city, which is to say in the world; More than 160 languages are spoken here.

She moved before the pandemic, when gentrification, with its “skyscrapers and glass condos,” drove her out of Dumbo, Brooklyn. Between the kitchen and the upstairs room, in one of whose corners are accumulated part of the five thousand pages of notes he took while writing, Desai (New Delhi, 54 years old) finished The loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, the monumental nineteenth-century novel in which he has spent almost two decades. In the United States, it was received as one of the books of 2025, and next week it hits bookstores in Spanish from Salamandra, with the translation by Aurora Echevarría.

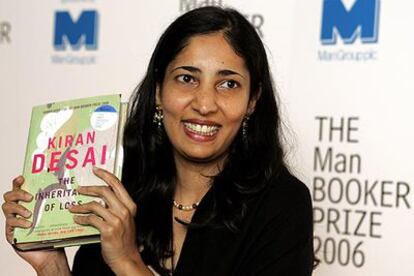

Desai, elegant, sweet and with a mischievous sense of humor, says that the pressure of continuing after the phenomenal success of The legacy of loss, which made her the youngest woman to win the Booker in 2006, disappeared long ago. He doesn’t remember exactly when, but he did give way to the complexity of the company he had planned. “I knew it would be a long book,” he says of a novel that he came to “fear that I wouldn’t be able to finish.” “Things were complicated by my interest in including a large cast of characters from different generations, and because I set out to treat loneliness from a global point of view, from Eastern and Western perspectives, viewing it as sustenance, as stigma and as political fear.”

The author apologizes because she does not know how to “work in any other way.” “For me, the ideas come first, and only then, much later, do I deal with the plot, which I spent maybe the last two years on,” he says. “I envy writers who know how their books end before they start writing them.” In his case, that end came when he was aware that introducing any change would have meant altering the entire novel. “There you realize that defects are necessary. That, in reality, the most useful thing about a book is what is wrong.”

The plot in this case pursues Sonia, an aspiring novelist, and Sonny, a budding journalist, across years and continents. Both are young Indians who experience the American adventure as a status symbol for their families, and both face daily the daily micro-racism of the immigrant, the strangeness of displacement and the loneliness of the new world. The book is also the story of those families, whose family trees welcome the reader in the first pages.

The action takes place at the end of the nineties, because it was then that “Indian nationalism broke out” and governed the destinies of the country at the hands of its Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and because Desai wanted to explore through the figure of the grandparents the “extraordinary changes experienced by the generation of those who passed from the British Empire to independence.” “Mine got married in an arranged marriage when he was 16 and she was 13. She was his second wife, because then infant mortality was very high,” he explains.

There are more parallels. She, like Sonia, studied in Vermont, with its long winters that, in addition to patience, test the capacity for introspection. She ended up in that corner of the East Coast when her mother, like Sonia’s, went against the conventions of the time and left her husband behind to accept a job as a literature teacher; first in the United Kingdom and then in the United States. The loneliness of Sonia and Sunny It is dedicated to her father, who, says the author, “never moved; he was so in love with the landscape.”

Desai, a member of the generation that renewed Indian letters in English, is the daughter of the writer Anita Desai, who lives, at 88, an hour north of New York. They are very united. When we arrived at her house, the daughter was dealing with her mother’s medical issue on the phone. When he hung up, he thanked us for the visit, because, he said, it had forced him to “clean up the dust” and “sort out the chaos” in the house. She lives alone, but lately she has some unwanted guests: “a family of large rats that have become strong in the garden.”

His mother, who was a Booker finalist three times, is not only one of his favorite authors (of her work, he recommends Baumgartner’s Bombay “about his German mother’s experience in India” and in custody); She is also his first reader. He grew up watching her write while “raising four children.” “For me, it was easier; I didn’t have to work hard to create that rhythm of life or the discipline that literature entails. It always felt completely natural to me to be at home in silence and working all day.”

She has been living with solitude easily for some time now, and enjoys “living obsessed with the news,” but “away from the literary world of New York.” It was upon moving to the United States that she discovered that the absence of company could also be a physical issue. “In India there are always a lot of people around you,” he clarifies. “You spend your time trying to find moments for yourself. A closed door is almost an insult; you never close one without someone throwing it open looking for an excuse to get in.”

The intimacy

This reflection on intimacy is shared by Sunny in the novel, when his habits clash with those of his girlfriend from Kansas. So, Sonia, who also lives in New York, is immersed in a toxic relationship with an artist much older than her: a self-satisfied cretin. He advises her not to write about arranged marriages or “orientalist nonsense,” and to avoid “magical realism,” which prompts an interesting reflection about what Western readers expect from an Indian writer like Desai.

Self-conscious, Sonia goes so far as to replace guavas with apples in one of her stories in another meta-literary nod: her creator titled Uproar in the guayabal his first novel, a satire about a Punjabi who is mistaken for a saint. Furthermore, Sonia’s grandparents send a letter proposing an arranged marriage to Sunny, which they both reject, considering it an obsolete custom, even though such unions are still “the majority in India,” according to Desai.

With that boldness of the grandparents begins the zigzag of an “Indian love story in the globalized world” that takes them from New York to New Delhi, from Goa to Venice, and from Paris to Mexico, where Desai spent long periods during the process of writing the book while trying “without much success” to learn Spanish. The writer confesses that she has visited all of these destinations because, although she is a novelist with plenty of imagination (capable of, as she said, The New York Times, writing “almost 700 pages (733 in the Spanish edition) and none of them being superfluous or boring”), he considers that “one cannot talk convincingly about places one has not been to.”

He also found closer inspirations for the story, such as the La Gran Uruguaya pastry shop, which is a couple of blocks from his house, in the middle of the pandemonium of the Latin area of Jackson Heights. He took us there to show the advantages, even with slightly below zero temperatures, of “living in a neighborhood full of stories that are waiting for someone to go look for them.”

In La Gran Uruguaya, Sunny drinks a “café con leche” (like that, in Spanish) and finally feels comfortable “among people who accept him as another person of color.” Desai ordered a vegetarian empanada. With a thread of voice barely distinguishable in the roar of the televisions that were broadcasting a concert of melodic music, the conversation turned to the most famous man of Indian origin in the place: the mayor of New York Zohran Mamdani. The novelist knows the mother, the filmmaker Mira Nair, and considers that the proposals with which her son won the City Council are “logical”, given “the cost of living is intolerable” in the city.

He also spoke about the paradoxical place that the Indian community occupies in Donald Trump’s United States. On the one hand, there is the second lady, Usha Vance, and a figure like Vivek Ramaswamy, who competed with Trump in the Republican primaries and now aspires to be governor of Ohio (“an embarrassing guy,” according to Desai). On the other hand, the xenophobic nationalism of America First has put them in the racist spotlight as the face of the beneficiaries of the HB-1 visa, designed for highly skilled workers. For the MAGA (Make America Great Again) world, they are coming to steal Americans’ jobs. “Racism towards Indians is growing a lot in this country. I think the community did not expect this; neither did the tariffs,” Desai said before leaving for his sought-after solitude in what is perhaps the quietest place in New York.

There his new literary project awaited him. For now, he is just “playing with ideas,” he said. But one thing is clear: he has no intention of embarking on a literary enterprise as ambitious as the last one. Your readers will appreciate not having to wait another 20 years.