We all know that we are going to die, no matter how bad it may be, but only geniuses can turn the final farewell to this world into a work of art. David Bowie was very conscious during the making of Blackstarin the first half of 2015, that his time in the realm of the living was running out, so he conspired so that this last example of his talent would become a quintessential work. A farewell that, far from incurring melancholy, looked towards a future already unattainable for its signatory: the twenty-sixth and definitive studio album by David Robert Jones is one of the most innovative and groundbreaking of his half-century career, a colossal 42-minute puzzle that even today, just a decade after the singer’s death (he died on January 10, 2016), is the subject of analysis and passionate debates among bowieólogos from half the world.

Bowie knew how to turn the imminence of his death into creative material of the first magnitude. The diagnosis of liver cancer had been communicated to him in mid-2014 but, far from plunging him into despair, it spurred him to prepare a farewell worthy of his legend. Only one person had news of the illness at the Magic Shop studios in New York, where the sessions of Blackstar They started on January 7, 2015 in complete secrecy, and not before all participants had first signed confidentiality clauses. It is endorsed by Tony Visconti himself, co-producer of the album and one of Bowie’s most faithful allies throughout his career, in the booklet of I Can’t Give Everything Awaythe recent and monumental box of 13 CDs that brings together all of the London artist’s recordings throughout the 21st century. “David phoned me to talk to me the day before the recording began. As soon as he arrived, he told me the worst news I would have wanted to hear. I was shocked. shockbut he tried hard to console me. “I was very sick.”

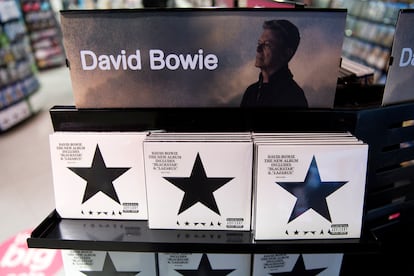

It is amazing to reconstruct, with full perspective, this final and majestic pirouette in the career of one of the most influential popular musicians of the last century. Blackstar It was released on January 8, 2016, coinciding with the 69th birthday of its author. Bowie died at his New York home on Lafayette Street just two days later. Incredible as it may seem, and although the album and its promotional videos were full of references to the last goodbye, no one knew how to interpret the hieroglyph throughout those 48 hours. Neil McCornick, newspaper critic The Telegraphpublished that same January 8th an extensive and superb analysis of the work, but admitted: “If we look for clues in his music, we are faced with the inscrutable.” And the final sentence is even more eloquent about David Jones’s astonishing ability to turn his swan song into a cabalistic exercise: “Like a modern pop Lazarus, Bowie is well and back from the afterlife.”

It took that fateful Sunday, January 10, for us to understand Blackstar in its true and metaphysical dimension. Now it’s hard to believe that we weren’t smarter. The extraordinary central theme, 10 minutes that are among the best of his career (which is saying something), was released as a preview in November and included, in a tone of plaintive prayer, stanzas such as: “Something happened on the day of his death. / The spirit rose a meter and stepped aside. / Another took his place and shouted bravely: I am a black star.” Lazaruswhich also gave the title to the work that Bowie was preparing in the off-Broadwaywhose rehearsals he could no longer attend due to his fragile health, showed him in the video clip blindfolded and was even more explicit: “Look up here, I’m in heaven and I have scars that cannot be seen.” AND Dollar Daysthe later composition, contained a gloomy play in its chorus: Bowie seemed to say “I’m dying to…”, but the pronunciation is almost identical to “I’m dying too.” Or, what is the same: “I am dying too.”

Once the context is known, it is impossible not to shudder before the elegiac component of Blackstara restlessness that can be uncomfortable even for the most devout. Marc Ros, leader and composer of Sidonie, a lover of Bowie to the core, promptly acquired his copy of the album that fateful January and has not unsealed it since then. “I haven’t been able to put it on, it makes me incredibly sad to hear his musical farewell,” he says. He keeps it neatly filed on his bookshelf, but it has become a personal taboo: “Right now I’m looking at its black spine, just to the right of The Next Day (2013), the previous album, and for now that’s where it will stay.” And it doesn’t seem like he’s going to reconsider his attitude anytime soon: “Many friends and music critics have told me that it’s very good. I have no doubt. But there will always be a new Bowie album to listen to, and that is Blackstar for me”.

The Barcelona singer-songwriter Litus, who materialized some memorable version of the White Duke when he was in front of Andreu Buenafuente’s television band, admits this painful dimension, but opens it to other perceptions and readings. “The first sensation is darkness, without a doubt, because David seems very aware that time is running out. But it is not a sad album,” he clarifies, “but rather enigmatic and serene, making his chameleon legend good until the end. And on a musical level, it is composed from the most absolute freedom. It is neither ancient nor modern, but timeless. Almost quantum.”

Sound was, certainly, one of Bowie’s main obsessions when approaching this last act. Determined above all that Blackstar was not a rock album, the artist and his inseparable Visconti managed to clear the equation when the composer Maria Schneider recommended a saxophonist from the New York scene, Donny McCaslin, whose presence would end up being preeminent and fundamental throughout the new album. Bowie wanted to meet him on stage, went to a concert of his quartet and, impressed by the band’s innovative and freewheeling character, decided to hire the entire band and thus incorporate drummer Mark Giuliana, bassist Tim Lefebvre and keyboardist Jason Lindner. This is how David spent it, capable of innovating and developing new ideas without a safety net until the final measure of the staff.

This capacity for “continuous changes of helm” is exactly what continues to amaze Eva Amaral and Juan Aguirre the most, the two halves of Amaral, who have never hidden their veneration for the author of Life on Mars and of which they recorded a famous version in Spanish of Heroes. “Blackstar It was unpredictable and different,” they reflect, “an atmospheric, intense and suffocating work, but at the same time beautiful, that is unlike anything they had done before.” They still find it difficult to choose it when it comes to uncovering an album by their idol, “because it is inevitable to listen to it with sadness,” but the anniversary has encouraged them to return to this kind of postmodern requiem in the first person. “We will return to it on some future trip,” they promise.

Indeed, Blackstar It is not the simplest, most instantaneous or most widespread album in the London genius’s overwhelming discography, but it may be the most transcendental. In all its meanings. Coinciding with these 10 years since his departure, these days we will hear many allusions to other enormous works, from Ziggy Stardust a Hunky Dory, Ashes to Ashes, Station to Station (celebrating its fiftieth anniversary), Heathen or the so-called “Berlin trilogy” (Low, Heroes, Lodger). But few admit so many and so complementary readings about a creator in permanent love affair with the enigma.

This is certified by a very recent biography of Alexander Larman, Lazarus: The Secong Coming of David Bowie (still without a Spanish version), which covers the last 25 years of the artist, since a tour in November 1991 with his failed band Tin Machine, and tries to unravel all his (very long) silences since in June 2004 he suffered a coronary obstruction for which he had to face a life or death operation. Always so premonitory, his 2003 album, Realitybegan with a beautiful and disturbing verse: “I never looked at reality over my shoulder.” And always committed to his work, he wanted I Can’t Give Everything Away, the beautiful last song from his last album, confirms that we will never be able to encompass his legacy. “I can’t give everything. I can’t reveal everything,” he warned us. Goodbye as one of the fine arts.