Nobody knew that this would be his last concert. But there she was. Dusted. Shivering, staggering and crying on stage at Kalemegdan Park in Belgrade, Serbia. Like an unprotected girl. In front of 20,000 people who booed her. Nobody considered that perhaps Amy Winehouse was not in a position to sing on that June 18, 2011. And nobody stopped her. The British singer with a raspy voice died just a month later in her bed, next to three bottles of vodka. He was 27 years old.

The music industry has changed since then. “Now artists are much more protected. They are not allowed to go on stage if they are not fit,” explains Domingo García, CEO of the representation agency Arriba los Corazones and former director of Universal Music. This executive has worked with singers such as Emilia, David Bisbal, J Balvin, Carlos Vives and Raphael, whom he accompanied to the Christmas special of The Revolt last year, the day he had the stroke. “I raised my hand and told (David) Broncano that we had to stop because Raphael was giving disjointed answers. We were scared,” he remembers.

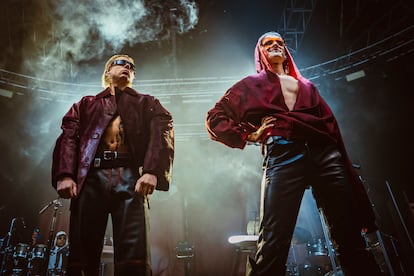

Currently, the physical and mental health of artists has once again been put at the center due to increasingly frequent temporary withdrawals. The latest, the Argentinians Ca7riel and Paco Amoroso, whose success has skyrocketed in the last year and a half, who announced last week that they had decided to put on the brakes to “rest and heal”; and also, in the world of entertainment, Andreu Buenafuente himself, who canceled his schedule, including the presentation of the New Year’s bells on RTVE, after an episode of stress. “There was a moment when I couldn’t do it anymore, I got out of alignment and my body said, you have to stop, and so I did,” he explained.

Many are faced with the stress, pressure, fatigue or speed involved in a profession that is more demanding than meets the eye. “This industry is constantly burning a club. That’s why there are so many singers who are in a bad situation with psychologists and psychiatrists. They leave it, they retire for a year… That didn’t happen before,” expressed the singer Álvaro de Luna in an interview in EL PAÍS a few months ago.

“I had anxiety and I was exhausted, but stopping is a privilege that not all artists can afford financially.”

I bite, singer-songwriter

Another of the last to stay away for a season has been Rozalén, who joins names like Delaporte, Lola Índigo or Vetusta Morla. The singer-songwriter from La Mancha has announced an indefinite pause in her career to take a break due to “emotional exhaustion.” Breaks that Quevedo, Pablo Alborán, Valeria Castro, Rigoberta Bandini or Dani Martín have also gone through, and those that Mikel Izal or Dani Fernández will go through in 2026, when their tours end.

What you don’t see about an “unfriendly” industry

“The music industry is not kind at all to mental health, but we are raising our voices more and more in public,” explains Julia Medina (San Fernando, Cádiz, 31 years old), finalist of Operación Triunfo 2018 and one of the candidates for this year’s Benidorm Fest. Artists usually talk about anxiety, depression and addictions, but what is behind these disorders?

“When you fulfill your dream, other things come into play, such as getting on the Spotify lists, the record company forcing you to compete with your peers, having to suck up to the radio stations to be played… The way the industry is organized is cruel. Every day I think about what it would be like if I were a primary school teacher, the degree I studied. I’m surprised that more people don’t abandon it,” the singer acknowledges.

An opinion shared by Diego Arroyo (Toledo, 36 years old), vocalist of the rock group Veintiuno. An architect by training, he has also felt the need to stop. “The pressure from constant exposure to statistics, numbers and trends exists. Each artist notices it in a way, and may not even notice it, but that does not prevent this pressure from happening in the background and affecting everyday life,” he explains.

The question of whether it is worth it is common among those who do not top the charts on the platforms. Among those who do not fill stadiums. Among those who have been in their careers for 20 or 30 years and have to adapt to a new, changing model that they do not fully understand. Or among those who develop their careers independently.

Communicating a temporary withdrawal is putting a clear framework to the industry and the public, almost a form of self-care.”

David Moya, Director of Communication at Sonde3

This is the case of Muerdo, stage name of Pascual Cantero (Murcia, 37 years old). At the end of November, he had to cancel the last three concerts of his tour. His body and mind told him “enough.” “I had anxiety and I was exhausted. I have been combining several bands in Spain and Latin America with everything that implies logistically, but stopping is a privilege that not all artists can afford financially,” he explains.

Stop or make important decisions, like Julia Medina did. He left Universal Music to have greater control over his career. “In each release, my only concern was that the song had good numbers so that they wouldn’t kick me out of the record company. At some points they sat me down at a table and told me: ‘Look, this is Spotify’s Top 50 list. You have to compose this type of songs’. And, of course, if it catches you in a moment of insecurity it’s easy to get carried away…”, he explains.

“My only concern was that the song had good numbers so they wouldn’t kick me out of the record company.”

Julia Medina, singer

This pressure to create a catchy chorus that goes viral on TikTok and catapults the song to the global charts makes many begin to doubt the meaning of their vocation. “There comes a day when you don’t know if you are making music because you like it or not to lower your levels.” rankings“, acknowledged Álvaro de Luna. Some rankings which also arouse suspicion due to the lack of transparency and the existence of artificial eavesdropping through bots and automated accounts.

The pressure of social networks

Another pressure is the requirement to be omnipresent on social networks so that the algorithm does not penalize them and take away their visibility. “This has reinforced the idea of the artist as a product for immediate consumption,” explains David Moya, Communication Director of Sonde3, an agency that organizes festivals such as Río Babel or SanSan de Benicàssim. “Emerging companies have it especially difficult and the anxiety to achieve quick results often leads them to chase the carrot of virality.”

To avoid falling into the maelstrom of likesvisualizations and listening, says Muerdo, you have to be “well planted in what you want and are as a musician.” “My biggest pressure is the one I put on myself. The fight for survival. The feeling that if you’re not doing things all the time you don’t exist, but this is not real. There is a base of followers connected to me beyond the data,” he adds.

The pressure to feed TikTok or Instagram generates a lot of stress for them, according to Domingo García. “Some people get depressed if they lose five followers,” explains the executive. Also, according to musical psychologist Rosana Corbacho, it disconnects them from their creativity. “I recommend that you do not take your cell phone to the studio. Networks isolate you and many lack physical and real connection.”

These dynamics impact in the same way on artists with experience and successes behind them. This was admitted by Nena Daconte, who retired to face her addiction and depression problems, in a conversation with this newspaper. “Numbers are valued more than art. If you don’t have many followers, they won’t hire you at a record company and it’s very sad, especially for those of my generation. We’re not used to being measured so superficially.”

Nena Daconte, singer: “My generation is not used to being only measured by followers”

A perception that the psychologist has also noted in her sessions. “They don’t understand why now they also have to be content creators and be so accessible. A patient told me that they required her to publish photos about her vacation and that she had a hard time because she needed a real break. I recommended that she plan the moment and the hour she was going to dedicate to the networks,” explains Corbacho.

Female artists especially suffer harassment in the digital world. According to a UN study, women are 27 times more likely to be attacked online than men. This October, Valeria Castro announced that she was taking a break after a wave of hate on X that criticized her guest performance on Operación Triunfo. In general, a large majority of comments question their physical appearance.

Canadian Nelly Furtado also retired. She has left the stage, exhausted from being called fat. “In consultation, I have only had one male artist with an eating disorder,” says Rosana Corbacho. “The rest were women. They feel that if they do not control their weight and appearance they will not continue in music. Sometimes, they abandon treatment and this, as a psychologist, is hard to see.”

The Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han, this year’s Princess of Asturias Award, explains that we are immersed in a society of fatigue based on performance, multitasking and self-exploitation. Something that leads to depression. “Here self-exploitation is marked by the crusher that is the industry. We all suffer from it. And we assume, for example, that we have to release a song every two months,” Julia Medina concludes.

The new times also cause anxiety. Because discs have a very short lifespan. They are published, promoted and disappear. And everything is for now: actions, filming, collaborations with brands… “If they go a year without releasing songs, people think that they are sick or that something is wrong with them. And this was normal before. We have to get the public used to missing them. Saturation is not positive for anyone,” complains Franchejo Blázquez, Dani Fernández’s manager.

After nine years of touring, headlining festivals and publishing three albums and a documentary, Dani Fernández will also take a break in 2026. “Announcing it is a way to put a clear framework in front of the public and the industry itself,” concludes Moya, who has brought artists such as Rayden, Travis Birds or La Pegatina. “A way to set limits and legitimize rest. It shouldn’t be necessary to communicate it, but, in this ecosystem, doing so is almost a form of self-care.”

Musicians “don’t quit,” said trumpeter Louis Armstrong, “they stop when there’s no more music in them.” Perhaps this is the main underlying reason. The need to stop to take care of yourself, regroup and connect with who you are away from the noise. So that the music returns to them again.