The morning of November 16 of the Franco-Algerian writer Boualem Sansal lasted almost a year. That day, at the Algiers airport, when he was returning home, he was arrested, taken to a secret services barracks and accused of terrorism, espionage and attacking the integrity of the state. He had been saying and writing what he thought about Islam, the Algerian regime and their relations for years. But recently the writer, one of the most translated and read in the French language, winner of the Novel Award from the French Academy, had declared to a magazine that part of the Algerian territory was part of Morocco. It could have been what broke the patience of the regime. Who knows, because the trial was a farce and he was sentenced to five years in prison, one of which he spent in deplorable conditions. Two weeks ago he received a pardon, granted at the request of the President of Germany, Frank-Walter Steinmeier. But the sentence is still valid.

Sansal, author of The Oath of the Barbarians (Alliance) or The German’s Village (The Aleph) has returned to Paris. But he doesn’t have a house. No money either, their accounts were frozen and the cards blocked. Until his life stabilizes again, he is installed in the impressive mansion of Antoine Gallimard, his editor, who has fought hard this year, together with the French government and the president, Emmanuel Macron, to have him released. The problem is that Sansal became a symbol of a cold war between the two countries, which are going through the worst moment in their relations since the independence of Algeria in 1962.

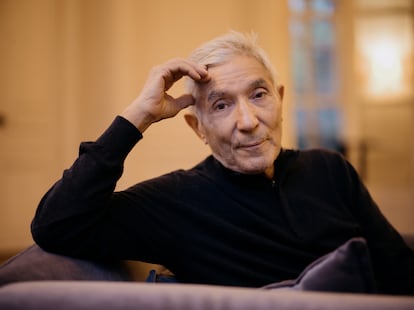

On Wednesday morning, much thinner and now without his famous ponytail, after having been number 4611 for a year, he received EL PAÍS and two other journalists from the Lena group at the Gallimard headquarters. Smile. “Yes, you could say it was a bit of a long morning,” he jokes as he settles into an armchair. That day I was nervously waiting, looking at the phone, for Algeria to release sports reporter Christophe Gleizes, sentenced to seven years in prison for advocating terrorism in a similar case. It wasn’t like that.

Ask. The memories will pile up now, but what did he do to last in prison?

Answer. There are two stages. In the first we are still what we were and we are facing something monstrous. We try to beat it. It’s prison, of course: the confinement, the isolation, the fact that you are very poorly fed and cared for. In the second, however, prison wins you. You are no longer a man, you are a prisoner, a number. And then shame appears, one feels humiliated. At first you fight against the judge: “No, it’s not like that, I didn’t say that.” One is still the owner of one’s own will, of one’s own words. And then, very quickly, for purely biological reasons, we become dependent on prison. It is she who feeds us, who does everything. She is the mother of the prisoners. And one finds a certain comfort. In addition, there are people who can become friends, routine, tranquility, old people. And there, from time to time, I caught myself thinking: “I’m dying.” That’s what it means. I no longer exist as a person.

P. Was there a moment when you lost hope?

R. On a sleepless night. It was dark. I became aware that it was over. You have to let yourself go, I thought. The prison is stronger. He is a monster that doesn’t think. The guards are automatons. They arrive with their keys, tock, tock, tock. They make gestures, slim, slim. It’s all you hear. It’s terrible. You recover some human life when, for example, you receive your lawyer—although mine never obtained a visa to come—or your family. My wife came every 15 days, half an hour in a parlor, separated by a glass and a telephone.

They put handcuffs on me. We went out to an abandoned parking lot and they put a hood on me before putting me in a car. “I was trying to orient myself by sound.”

P. All recorded, of course.

R. In my case, yes. For the others, no. They put me in a special booth, number 1. It was clear because, simply, everything was recorded there. You enter like a flock: families, wives, fathers, mothers, children. And on the other side, the prisoners. But when you say something you don’t like, the sound cuts off.

P. Did you think something like this could happen to you?

R. Yes and no. They consider me an opponent of the regime, but I am a simple citizen. And when I write, in my books I tell things as they are. Because when I write I don’t think about publication; I simply write, I say what I think. And then, at a certain point, the question arises: should we publish or not?

P. Were you not aware that something could happen to you if you returned to Algeria with what you said about the regime?

R. Well, honestly, no. The truth is that I am still very childish in my head. If I have something to say, I say it. Only later do I realize that I shouldn’t have said it, or not that way.

P. Why do you think that was?

R. An opportunity presented itself in the midst of the crisis between the two governments, a secret, latent crisis. Algeria obviously reproaches France for colonization, for example. But it is clear that it is a pretext. When France decided to recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, it was a shock for the Algerian power. And suddenly, Spain did it too; and then, the United Kingdom, the Security Councils. And they took it as a challenge.

P. It does not seem like a great strategy to regain the trust of other countries.

R. It was not good publicity for Algeria, of course. I think they were overwhelmed by the situation. They thought that everything would remain at the diplomatic level, that France would intervene a little, that there would be negotiations. But in reality they were faced with a very strange phenomenon. They did not expect a mobilization of such magnitude.

P. Were you aware of being a piece on the board of the political game between France and Algeria?

R. Yes. I was detained by the secret services. Arrested by people who refused to identify themselves at the airport. They took me underground. A labyrinth of tunnels, of corridors. And then three or four guys walked in dressed somewhere between an Islamist and a neighborhood thug. They are spies who mix with the population. They put handcuffs on me. We went out to an abandoned parking lot and they put a hood on me before putting me in a car. I was trying to orient myself by sound. And after 20 or 30 minutes at high speed, while the horn sounded, they entered alleys, a metal gate opened and they made me get out.

P. Where was it?

R. Between, and secret services headquarters with a biblical name. There, during the civil war, Islamists who were arrested were tortured and then thrown into mass graves. I spent six days there in filthy conditions. They do it to break you, to make you say anything. The accusation is prepared in advance. When they decide to arrest you, it is already written: espionage first, terrorism second. That already implies the death penalty. Then, an attack against the security of the State, things that already amount to prison crimes, 20 or 30 years. It is the prisoner who must provide proof that he is guilty. For six days, he always responded evasively to every question. And each time I told them: “If you want me to respond, identify yourself. Who are you? What service?” They came back one morning: “Wash, get ready.”

P. And what happened?

R. It was there that I learned that I was accused of espionage and terrorism. I thought he was dead. He was 80 years old. Then they transferred me to jail. They search you, they strip you naked. You no longer have a name, you no longer have anything. And they give you a number that I wrote on my arm so I don’t forget it: 4611.

P. Did the mobilization reach inside the prison?

R. Not at first. I was in a maximum security sector with Islamists and terrorists from Daesh, Chechnya and all theaters of Islamist operations. They were Algerians who had gone to fight here and there, and who finally returned.

P. Didn’t you talk to the Islamists?

R. No, they are Islamists. They don’t speak a word of French, and I speak very bad Arabic. Besides, we have nothing to say to each other.

P. For a writer it could be interesting to know them.

R. I tried to talk to some of them, yes, but I know them well anyway for other reasons. We spent the day sitting in the patio. But the Islamists do it in front of the wall, as if it were the Wailing Wall, praying all day.

P. Are you going to write about your detention, about those months you spent there?

R. I don’t like prison literature very much. There are many, and also many fakes. The topic has been discussed a lot in cinema. And I either tell everything, or I don’t tell anything. And here I’m missing elements. It has no interest. And besides, I don’t want to talk about myself. What am I going to tell? Prostate problems, my cancer?

P. Could I write there?

R. We didn’t have anything to do it with. But what I needed most was reading. A writer is someone who reads, who reproduces what he has read. I discovered this theorem. Read, see, listen. That’s the biological part. Writing is the artificial. What one has read is written in another form. But I didn’t have books. If you ordered an Islamic work, however, you had it instantly. You wanted a small Quran, a large one, a medium one, they gave it to you.

P. Do you want to return to Algeria?

R. Yes. The pardon does not annul the conviction. I am still a condemned man, doubly so. I will not get my rights back until the end of the five years. So I will return to Algeria. I told everyone: on television, to Macron, to Jean-Noël Barrot (foreign minister). For me it is a question of principles. They condemned me, okay, they went too far, but still, they can’t forbid me to go. Three days ago they deactivated the chip of my passport.

P. So how do you plan to get in?

R. With my French passport, but a visa is needed. And they won’t give it to me. So I’m a little stuck. But maybe it will go the same. I’ll probably get turned away at the airport or maybe detained.

P. But why take the risk if you can be arrested?

R. There are things that cannot be accepted. So I am ready for anything, even going to prison again or dying there.