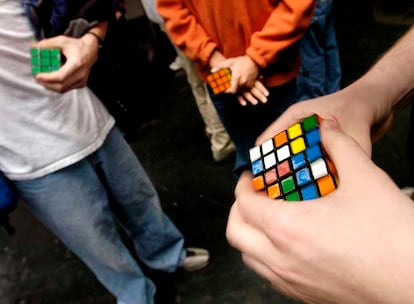

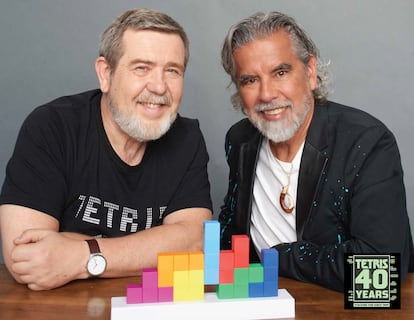

“This,” says Aleksei Pázhitnov with a messy Rubik’s cube in his hand, “is my favorite puzzle. But I also think it is, quite simply, one of the best things humanity has ever invented. If we could only send ten things into space, this would have to be one of them.” Next to Pázhitnov, who revolutionized the digital world when he created the best-selling video game of all time, the Tetrissmiles the father of the cube himself, Ernő Rubik. Both give interviews on rare occasions, but they have agreed to speak with EL PAÍS at the OXO Video Game Museum, in Malaga. Rubik, who spends half the year in San Pedro de Alcántara (Málaga), went this Friday to the museum, a temple of creative leisure packed with children, where Pázhitnov will receive an honorary award this Saturday.

The talk is a tectonic clash between two minds that knew how to combine leisure, creativity and mathematical challenge. With one difference: you can’t be more analog than a Rubik’s cube, and you can’t be more digital than the Tetris. The meeting begins with the mutual memory of how they discovered each other’s creation: “I spent two months trying to solve it. And I managed it without help. It is one of the great merits of my life,” Pázhitnov confesses, laughing. And Rubik? How did you find out about Tetris? The father of the cube returns the compliment: “When we launched the cube in Hungary in 1974 it was very successful, but obviously many things did not reach my country, which was behind the Iron Curtain,” he remembers. “The success of the cube allowed me to travel, buy computers, get closer to many things that were sold in the West. I am not such a digital man, but I love geometry, and I saw the potential of the Tetris as soon as I laid my eyes on the game on a trip to New York.”

There are those who Tetris and Rubik’s cube are considered games, there are those who consider them mathematical challenges, and there are those who consider them a prodigy of design, elegance and simplicity. But beyond their functionality, the truth is that they have had a decisive impact on the culture and society of the last half century. Rubik, a Hungarian architect born in Budapest 81 years ago, invented the 9×9, six-color cube that he holds in his hands in 1974. He designed it, in principle, as a pedagogical tool to explain three-dimensional concepts to his students. In 1980, the toy company Ideal Toy Company marketed it internationally under the name with which we all know it: Rubik’s cube; and since then it became a global phenomenon, both for its mental challenge and for its simplicity and accessibility. It is impossible to calculate how many cubes have been sold between originals and copies, but with the registered trademarks alone it is estimated that almost 500 million.

For his part, the Tetris It was created by Pázhitnov (Moscow, 70 years old) in Moscow in 1984 – originally, on an Elektronika 60 computer. He designed it as a puzzle based on geometric pieces that fall and must form entire lines. In 1988, its international expansion began when several companies on this side of the Iron Curtain bought the license for the game, and its popularity then skyrocketed, when it was included with the Game Boy portable console in 1989 and with the release of portable devices specifically designed to play it. Since then it has been adapted to dozens of platforms, becoming a universal video game classic, with hundreds of versions (and plagiarism, of course), including its adaptation to all types of devices and its jump to virtual reality. With hundreds of millions of games shipped, the truth is that Pázhitnov did not initially receive royalties for the game, since these were the property of his employer, the Government of the then Soviet Union. He only began to obtain copyrights in 1996, when he and Henk Rogers formed The Tetris Company. Rogers, who accompanies Pázhitnov Málaga, walks through the corridors of the OXO museum, stopping his gaze on the devices on display while the talk takes place.

Both creations, cube and Tetrisare the crystallization of mechanical elegance and the demonstration of how simple artifacts can contain very complex and fun dynamics. They are like sheet music, ready to be reinterpreted by new generations. In fact, if there’s one thing Pázhitnov is proud of, it’s that digital pioneering spirit: “Now that I look back, if there’s one thing I think I can be proud of, it’s that the game helped bring people closer to computers,” he explains. “So those devices were serious things, in a way unpleasant and that commanded a lot of respect from people. And, suddenly, there was a very simple, very accessible game that people could interact with on a computer.” And boy did he do it.

Cognitive challenge in the era of comfort

There is a word that both use effusively in the talk: “challenge.” At a time when the vast majority of content consumption is passive —reelssilly videos, series consumed in the background and even news that ends in the headline—it is worth remembering that these two devices challenged people: they pushed them to improve, or to think in order to complete the challenge they proposed. “Of course! My big concern today is Artificial Intelligence (AI),” says Pázhitnov: “It is preventing people from thinking, from facing challenges. It is this type of entertainment that challenges us that we have to look for,” he says, pointing to the cube on the table in front of him. “We will have to see if AI becomes as intelligent as us,” adds Rubik, “but progress always has contradictions: the greater speed of a vehicle helps us get to places sooner, but it makes accidents more serious. Everything has positive and negative effects.” “¡You get your sweet but you get to pay! (You will have the sweet, but you have to pay the price), Pazhitnov exclaims. Rubik elaborates: “AI seems to have come to defeat nature. Well, that can’t be done. What we have to guarantee is not that AI is better than us, but that this technological revolution provides solutions to our problems. It’s that simple.” “And that it helps us think not more individually, but as a society,” says Pázhitnov.

“You have to discover what is best about your idea,” reflects Rubik. “And trying to find the perfect solution is complicated: almost everything can be refined and improved. The greatest discovery, in reality, is to teach a direction: to point out where we should go. Try to imprint a state of mind on people that drives them to achieve great goals,” he reflects. What is the strangest situation in which you have seen someone play the game? Tetris or was he trying to solve a Rubik’s cube? Pázhitnov is clear about it: “Many bosses of computer companies have confessed to me that they once installed viruses on their employees’ computers so that they would erase the Tetris if they installed it,” he laughs.

And what would you say to a young creative who has to function in this uncertain 21st century? “The only advice I can give is ‘listen to yourself’. Never listen to what the marketing or the trend. Look for what makes you feel happy,” says Pázhitnov with conviction. For his part, Rubik has two: “The first: be curious (during the entire conversation Rubik has praised the innate, almost childlike curiosity, which according to him should guide human behavior). And then, never give up before facing a serious problem. If you can’t solve it, maybe it has no solution; but if you face it, maybe you will realize that you can improve enough to solve it.” A lesson that cannot be crystallized better than in these two artifacts, Tetris and Rubik’s cube, kings of analog and digital, which will surely continue to entertain (and challenge) people for many decades.