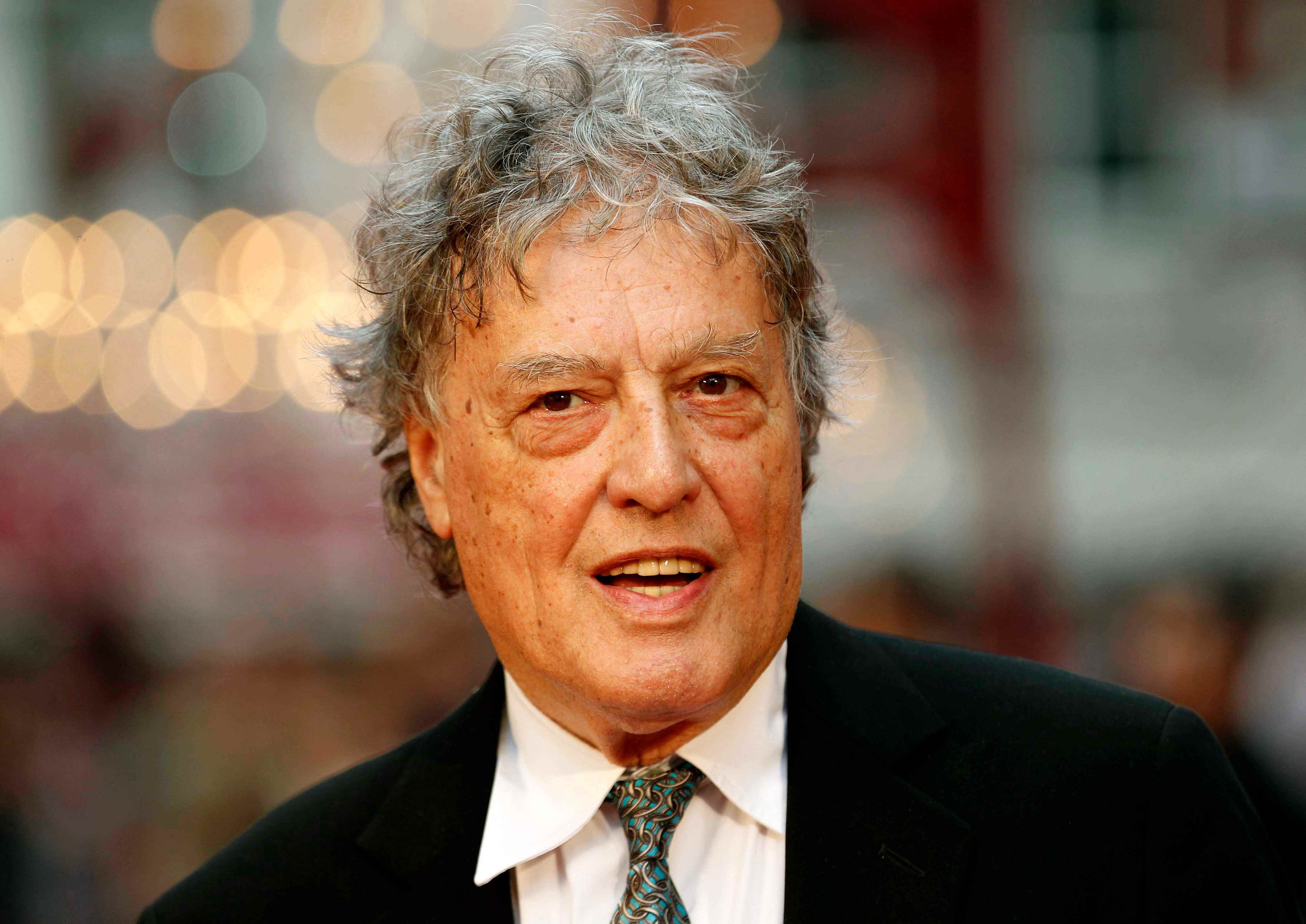

Like many others who embrace the British soul by destiny, not by birth, Tom Stoppard (born in Czechoslovakia under the name Tomás Sträussler) became over the years a national treasure of United Kingdom literature. The playwright, author of works such as Rosencrantz and Guildersten are dead. or the film script Shakespeare in love, for which he received the Oscar, died this Saturday at the age of 88 at his residence in Dorset, surrounded by his family.

“He will be remembered for the brilliance and humanity of his works, for his wit, his irreverence, his generosity of spirit and his deep love for the English language,” United Agents, the agency that represented the playwright, said in a statement.

He worked for radio, television, film and theater. He defined himself as a conservative with a small c, almost a liberal, with a deep concern for human rights, political freedom and censorship, which he conveyed in many of his early works.

He left Czechoslovakia with his parents, two non-practicing Jews, to begin a life as a refugee that took him to Singapore and India until he ended up in England in 1946. His father, according to Stoppard himself, drowned on the ship he was trying to escape from the Japanese army. A doctor by profession, he served voluntarily on the British side.

The playwright, decorated and knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, began as a journalist. He immediately began writing short works for radio, until in 1960 he presented his first creation for the stage, Enter a Free Man (A Free Man).

Stoppard was able to address in an ingenious and brilliant way problems and questions of complex philosophical depth, to which he gave a narrative structure and agility that seduced millions of viewers. Something that is clearly reflected in one of his most famous works, Rosencrantz and Guildenrsten are dead.which revolves around the lack of self-determination and the irremediable fate of two secondary characters in the Hamlet by William Shakespeare who do not understand what their role really is in that great tragedy, all told with a very humorous stoppardiano. For that work, first presented in 1966 at the Edinburgh Festival and performed two years later by the National Theater Company, he won four Tony Awards, including best play.

Lovers of the cinema and literature of another great giant of British literature, John Le Carré, know that Stoppard’s hand is behind one of the most exquisitely constructed film adaptations, which did not miss a single shot or a word, as it was The Russia House.

His theatrical production was very extensive. He signed more than thirty works, in which he displayed a magnetic intellectual sophistication. The adjective ‘stoppardian’, which is included in the Oxford English Dictionary, is defined as “the use of elegant wit when addressing philosophical questions.” In Jumpers (The Jumpers), the arrival of British astronauts to the moon while a group of radical liberals take over the British Government, serves Stoppard to make a complex satire on academic philosophy, loaded with quotes and references. Many critics consider it his masterpiece, although others criticized it for unnecessary artificiality that alienated many viewers.

It didn’t matter. The author never renounced a complexity and variety of ideas and arguments that his many followers appreciated. In Arcadiastaged in 1993, the relationship between a precocious teenager, obsessed with science and mathematics, and her tutor, a poet friend of Lord Byron, the plot serves to debate the relationship between the present and the past, certainty versus uncertainty, chaos theory and even the different schools of landscaping and gardening.

Stoppard’s creativity was required on many occasions to put the finishing touch on cultural products intended for the masses. His hand is also in the scripts of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusadeor in Star Wars, Episode III: Revenge of the Sith.

Although it does not formally appear in the end credits, it is public knowledge that part of the dialogues from Schindler’s List They came from Stoppard’s head, or the playwright took care of polishing them. Legend has it that director Steven Spielberg even forcibly took him out of the shower because he urgently needed to consult some ideas during filming. In fact, Leopoldstadtthe last work written by the author, which premiered in 2020 at the Wyndham Theater in London’s West End, was praised and considered by critics as a Schindler’s List for the tables. With many personal and autobiographical keys, it tells the story, in the first half of the 20th century, of a wealthy Jewish family settled in Vienna, where they arrived after fleeing the anti-Semitic pogroms unleashed in Russia and Eastern Europe. All four of Stoppard’s grandfathers and grandmothers died in concentration camps at the hands of the Nazis.

His trilogy The Coast of Utopia (Journey, Shipwreck, Rescue), for which he won a Tony Award, addresses the philosophical debates present in pre-revolutionary Russia at the beginning of the 19th century.

Perhaps because of his own personal history, and because of an inveterate defense of individual freedom, Stoppard did not share the leftist ideas of other playwrights of his generation. Without making great public exhibitions of his political ideas, with a rather solitary and individualistic personality, he did not hesitate at the time to support the conservative revolution that marked the arrival of Margaret Thatcher. Married three times, revered by his friends, such as Rolling Stones singer Mick Jagger, who paid tribute to him this Saturday on social media, Stoppard had an elegance and presence that, however, did not produce resentment in his competitors. “One of Tom’s greatest achievements is that he has made us not envy him anything, except perhaps his good looks, his talent, his money and his luck,” another established British author, Simon Gray, also ironically stated.

Curiously, the great playwright of ideas always had journalism as his initial vocation. “My first ambition was to be on the ground of some African airport while bullets from a machine gun flew over my typewriter. But I was no good as a reporter. I never thought I had the right to ask people anything. I always thought they were going to hit me in the head with the teapot or that they were going to call the police,” he explained to the Reuters agency in an interview.