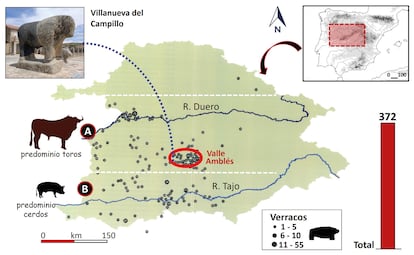

In the second century BC. C., the Vetones – a Celtic culture that occupied the center and west of the Plateau – achieved a high degree of social and economic development that turned them into a kind of “tribal state”. It was a hierarchical society that lived in fortified urban settlements (towns), ruled by a military aristocracy that based its wealth on livestock, mainly cattle and pigs. For this reason, they placed large stone sculptures of these animals (popularly known as boars) around their cities and in pasture areas and springs. A type of signs that marked, among other meanings, that one was entering a pre-Roman town with its own characteristics. Archaeologists have registered more than 400 of these specimens, about 200 of them in the province of Ávila alone.

The largest of all of them, which is also the largest sculpture chiseled in the West by this Celtic people, is a 15-ton boar that can be admired in the main square of the Avila town of Villanueva del Campillo (101 inhabitants), even though that is not the place where the Vetones originally placed it, which sparked controversy when it was moved there two decades ago and which has not yet been resolved. The Cultural Heritage Commission of Ávila agreed in 2005 that it should return to its original location, on the outskirts of the town. However, the Ávila Provincial Council and the City Council have turned a deaf ear until now.

The municipal group of Izquierda Unida has proposed a solution on several occasions: move the original and leave a replica in Villanueva del Campillo. But it has also been ignored, as have the repeated requests of specialists, who consider that the sculpture should be contemplated where the Celts placed it. The last to remember it are Jesús Rodríguez Hernández, Jesús R. Álvarez Sanchís and Gonzalo Ruiz-Zapatero, archaeologists from the universities of Salamanca and Complutense of Madrid, who have recently published a study (Granite rough. The vettón bull of Villanueva del Campillo and the boars of the Amblés Valley (Ávila), published in the magazine Earty where They recover the story of the boar and demand that it return to its original place.

The figure was found in a place known as Tejera Vieja, in the municipality of Villanueva del Campillo, where specialists from the Ávila Museum found at the end of the 20th century two sculptures that remained half-buried on the divide between two properties in a meadow. One represented a pig and was of medium size, and the other reproduced a bull of “truly exceptional dimensions (250 X 243 x 150 cm),” the study recalls. The stone figure of the bovine is, “by far, the largest zoomorphic stone sculpture in the Veton area and most likely in the pre-Roman statuary of Western Europe,” experts say.

The two specimens were found lying down. The bull was missing its hindquarters. Therefore, a search for its paws began in the area, but with unsuccessful results. In 2003, with funding from the Provincial Council of Ávila and the collaboration of the Regional Government of Castilla y León, it was agreed to build a stone enclosure immediately at the site of the discovery – a space of about 25 x 25 m – where the boars would be raised, respecting the original orientation, with their heads facing west and a path enabled to access the site from the municipality.

As the largest of the boars was missing its hindquarters, it was taken to Ávila and restored with a cast bronze prosthesis. At the end of 2004, it was temporarily exhibited along with another large bull, from the municipality of San Miguel de Serrezuela, in the Corral de las Campanas square, in the capital of Avila.

The Villanueva del Campillo City Council then pressed to display it temporarily in the main square of the municipality along with the minor figure with which it was found. The idea was that from there it would go to its original location, but so far that has not happened.

The three archaeologists conclude in their study: “This is an excellent opportunity to show the boars in the landscape where they were born, the landscape that surrounded them and their meaning. If we divorce the sculptures from their original context, we lose the possibility of showing the archaeological find in its landscape matrix. We turn it into a castrated archaeological heritage. Sometimes the values of the old boars do not They end up being understood by today’s vetons, because showing the past and delighting through these granite brutes requires ingenuity and discernment.”

The Amblés valley or upper basin of the Adaja river is a region in the center of the province of Ávila that concentrates numerous veton archaeological sites that include two hundred boars, some shaped like a bull and others like pigs. There may be many more, but they have not yet been located because they are buried or have been displaced from their original locations. The authors of the study say that they were “a kind of brand or identity seal.”

Admiration for these granite figures began in the Renaissance period, when they were valued “as monuments worthy of being preserved and interpreted, which implies their transfer to emblematic places (bridges, squares, walls…) with a reciprocal ornamental purpose: the boar beautifies the environment and it exalts it, and implies an installation of enhancement through pedestals and islands of respect, contributing in this way to increase their social esteem”, indicate the archaeologists.

Both carvings were placed by the Vetones at 1,400 meters above sea level, right at the entrance to the Amblés valley, and occupied “the most visible place in the environment.” They were aligned in an east-west direction with their heads facing the sunset. “That is, oriented in such a way as to offer maximum volume and greatest visibility when accessing the natural entrance route to the valley.” The archaeologists, to demonstrate this, reproduced the figure of the horn in wood in its original place and verified that it was visible from more than two kilometers away.

Its location at the entrance to the valley marked the richness of these pastures, conferred a protective value on the nearby towns and also constituted “a warning to enter a specific territory. Perhaps a kind of warning about stepping on other people’s land,” the archaeologists assert.

The bull’s stone comes from a quarry located one kilometer away. The transfer of the block or the finished sculpture was possibly carried out on wooden carts. Its enormous weight made it necessary for at least six to eight men to intervene in its turning and lifting.