“I’m going to eat a snack and buy medications in the pharmacy. I come back soon.” They ran three in the morning of March 18, 1976 in Buenos Aires and Tenorio Jr. wrote this phrase in a note left in the room. The Brazilian pianist was at the Normandie Hotel, located in Rodríguez Peña 320, a few meters from Corrientes Avenue, central axis of the Buenos Aires bars and shows, when he went outside without worries and proud: the previous night he had slid his fingers with frenzy and elegance by the keys of his pian Two of the most important figures of his country’s music. A top -level concert in a top -level room, which gave a good account of its talent, recognized for a long time in Brazilian jazz to know how to include in the bossa nova The nerve of bebop. Rhythm, class and modernity. Tenorio Jr. was a man who represented the new times in the culture of the entire American continent. However, that note was the last thing that was known about him. He never returned. He was kidnapped and killed by Argentine military. For decades, nobody knew where his body was.

Almost half a century after its disappearance, the Jr. tenorious body has been identified thanks to the comparison of fingerprints. As announced by the Argentine Team of Forensic Anthropology (EAAF), a scientific, non -governmental institution and in charge of the search, recovery and identification of missing persons, theirs is part of a set of five people buried as NN -not identified and known thus in the medical field at the time of Latin I don’t know the name which translates as’ without any name’-. The researchers have concluded that Tenório was buried in the Cemetery of Benavídez, Tigre party, where many corpses found in public roads during Argentine military repression were transferred. Thanks to the documentary information, it is known that most cases of NN passed to Osario, that is, they ended up in common graveyard graves. However, his body could not be recovered, because it is believed that since October 1982 that grave was occupied by the remains of other people.

For more than a decade, this identification has meant a long and patient documentation archeology process. The EAAF works with two types of identifications: the one that is done through the DNA, which is possible to extract from the remains found in graves or cemeteries, and another more complex that is achieved with a special software through the comparison of fingerprints that work in public records. With this last system, more than 140 victims of Argentine state terrorism have been identified. “This work involved reviewing judicial historical archives to select those causes that meet certain characteristics that we know are coinciding with the ways used by the repressive system to have their victims,” explains Natalia Federman, attorney for crimes against humanity for EAAF and a lawyer specialized in human rights. “Then, we study them to see if there are clues that allow the identification of the victim. In the case of Tenorio, there was a fingerprint game that could be compared and thus achieve their identification.” Tenorio tracks were more difficult to find than normal because their fingerprints did not appear in Argentine public records because they were Brazil. Therefore, you had to go to context files and pull the accumulated experience after decades of search of missing persons. “In 1976, his body appeared on public road Director for Argentina of the EAAF. His cause, therefore, was kept in a judicial file in San Isidro, north of Buenos Aires, in which the discovery of an unidentified body was discussed two days after the pianist’s disappearance. That body was that of Tenório Jr., a wizard of the keys, shot to bullets and lying on the street like garbage.

What happened in 1976 between the night of March 18, when the musician went for a walk, and on the 20th of the same month, when his body was collected by the police in a field on the Pan American Route, corner with Belgrano Avenue? Resolving this mystery was almost impossible for years because the disappearance was never investigated because of the conspiracy between the Argentine and Brazilian dictatorships. While it is true that the coup d’etat in Argentina occurred on March 24, 1976, when the Brazilian dictatorship had been imposing its iron fist for more than a decade, the military already operated violently in Buenos Aires for the early hours of March 18. The pianist had to be assaulted by a group of uniformed that was known to the dawn of the proclamation of the dictatorship. In fact, with Videla and its generals in power, the Brazilian embassy in Argentina raised on April 5, 1976 the petition of the Brazilian music society, to which the musician belonged, so that his search began. It was never done. Meanwhile, Vinícius de Moraes dedicated himself to the tireless task of finding his whereabouts and turned to different diplomatic calls that never resulted.

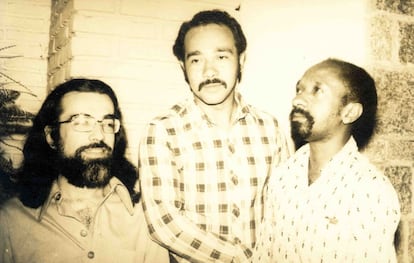

From the first day of the disappearance another question arose, perhaps the most painful to solve: why was the pianist arrested and killed? With his long hair, populated beard and black glasses, in the purest Bill Evans style, the influential American pianist who could see a year earlier during a concert in Rio de Janeiro, Tenório Jr. did not go unnoticed: he appeared good alive of jazz. A hypothesis is that this policeman without outstanding political inclinations could be confused with another person, as the guitarist Toquinho said. Another, however, is that the military knew perfectly who the pianist was and saw him as an enemy. After all, the jazzman Brazilian, with his music that appealed to a prodigious creative freedom and a mental and spiritual liberation, symbolized everything with which the coup plotters wanted to end. In this sense, Claudio Vallejos, Cabo and member of the Secret Service of the Argentine Navy, gave in 1986 relevant information that could never be checked. As he said in an interview with the Brazilian press, the musician had been taken to the Navy Mechanics School (ESMA). There, he was tortured by Argentine and even Brazilian military and, finally, executed with several bullet shots by Alfredo Astiz, one of the most famous repressors of terrorism of the Argentine dictatorship, known as The angel of death. Be that as it may, his disappearance, as they assure from EAAF, was one of the many state terrorism actions that framed in the well -known Condor Plan, the repression campaign that Latin American dictatorships carried out through the continent with the support of the United States.

The disappearance of Tenório Jr., born in Rio de Janeiro, was a reason for a short film and a television documentary in Brazil, without much importance outside the country. More relevant was the animated film that Fernando Trueba premiered in collaboration with designer Javier Mariscal. They shot the pianist, Also turned into a graphic novel (Penguin Random House), was the result of a journalistic investigation of many years on the disappearance. The Spanish director, winner of an Oscar for Beautiful eraHe spoke with his wife and children and did several interviews with the idea of shooting a documentary that finally became animated film. For Trueba, the Brazilian musician became an obsession. “There was a time when I was not interested in talking about anything other than Tenório Jr.,” he confessed in an interview in The weekly country on the occasion of the premiere of They shot the pianist.

The name of Tenorio Jr., barely known outside the melómanos circles of the Bossa Nova, It is synonymous with musical greatness. An interesting artist who stood out from a young age in Brazil. “It was part of what was called Samba Jazz. A new Brazilian jazz language also fostered by Edison Machado, Zimbo Trio or Tamba Trio. From that movement came out to EUME Deodato, which sold millions of records in the United States,” explains Carlos Galilea Brazilian music and program presenter When elephants dream of music of radio 3. “When she Fitzgerald sang in Copacabana, she did not do bises because she left before, she crossed the street and was going to see the clubs to these musicians, among which she included tenorium,” Galilea adds.

According to Ruy Castro, musicologist and author of the essential essay Bossa nova (Turner), tenorio was one of the flag bearers of the hard bossa novavariant of the jazz samba, recognized by a heavier sound than the original genre that put Brazil on the map as a fascinating cradle of world musical creation. In Castro’s words, if João Gilberto had passed through Beco, the Bohemian premises of Rio de Janeiro where Tenório Jr. played since 1961 with his quintet Bottle’s, he would have “became horrified” of how they reinterpreted their songs, more forceful and giving good tract to the drumsticks of some batteries that barely sounded at the time. In the background, tenorio carried the precepts of the bebop of the fifty to the Bossa Nova. Well demonstrated in the only album he recorded with only 22 years, a hidden jewel called Stuff (1964) in which he plans the influence of his admired Bill Evans, but also all that expressionist form of the hard bop already then in full hatching. The Brazilian pianist sounds as if Horace Silver or Herbie Hancock were hunched up with the sunsets of Rio de Janeiro. “We will never know that he could have happened to him. He was talented and had 50 years ahead,” says Galilea.

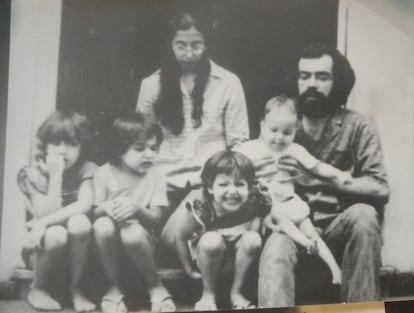

When Tenório Jr. was kidnapped and killed in Buenos Aires he was 34 years old. In Brazil, his wife Carmen Cerqueira was waiting for him, who was pregnant, and her four children. The fifth of the children, Leonardo, was born only one month after his disappearance. Carmen told Fernando Trueba that she was still married until she appeared. Since 2011, he is remembered in Buenos Aires with a plaque on the facade of the Normandie hotel, the last place where he was seen and left that note. “I’ll be back soon,” he wrote. He did not.

Today, finally, as if it were the story of the most tragic jazz song, it is known why he did not return.